Politics

What The JDU-RJD Alliance Means For Politics In Bihar

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Aug 16, 2022, 04:56 PM | Updated 04:56 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Six months ago, this writer wearily concluded that the assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh were the toughest to forecast accurately.

While it was plainly evident that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) would receive a handsome mandate once again, and that the Samajwadi Party would improve enough upon its 2017 performance to make the 2022 contest nearly bipolar, a trend of constantly-shifting alliances frustrated the precise, quantitative prediction of seats and vote shares.

However, Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s recent decision to dump the BJP, betray the popular mandate that alliance received in 2020, and join hands with the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) once again, has knocked Uttar Pradesh off the top spot on a list of polls-hardest-to-predict-without-divine-intervention. Bihar’s electoral dynamics has become extremely confusing and unpredictable.

Nonetheless, it is imperative that we sift through the tumult, if we are to figure out what lies in store. This exercise becomes all the more necessary, since many commentators in mainstream media view Nitish Kumar’s volte-face as the first major step in efforts to cobble together a worthwhile opposition alliance ahead of the 2024 general elections.

Could the next gana-pati be from a confederacy of Vrijji, Magadha and Anga, or will it be the sevak from the mahajanapada of Kashi once more?

On the face of it, a resurrection of the Mahagathbandhan (MBG) in Bihar, primarily constituted of the RJD, Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) (JDU), the Congress, two Marxists parties (the CPI and CPM), and one Maoist party (the CPI(ML)(L)), gives the coalition a clear edge over the BJP’s National Democratic Alliance (NDA), in terms of both seats and vote shares.

The NDA, in fact, is now down to just one ally - the Lok Janshakti Party (LJP) of a capricious Chirag Paswan, which has numerous pockets of significant support across the state. Even a fringe ally like former JDU chief minister Jeetan Ram Manjhi has left the NDA to join the new MGB cabinet.

But that’s exactly where the confusion begins.

First, no party in Bihar has the electoral depth to dream of pursuing a simple majority in assembly elections on its own. Leave aside individual parties, no coalition has polled above 40 per cent in the past two decades, save the NDA by a whisker in 2020.

Second, although the bulk of the contests in Bihar are, and will be, a direct faceoff between the MGB and the NDA, bipolarity is still fairly low. This is because the ‘Others’ continue to command around a quarter of the votes. As a result, even minor swings can upset delicate caste-coalitions and affect outcomes.

Third, alliances of the past two decades had muted the influence of the minority vote, and pushed the RJD’s infamous Muslim-Yadav axis to the side-lines. But with his flight to the MGB, Nitish Kumar has resuscitated the relevance of the Muslim vote bank.

The winning coalitions of this century were more caste based than caste-plus-faith based, with the Muslim vote only providing the cherry on the icing when the RJD and the JDU were aligned in 2015.

This had much to do with the BJP’s successful expansion of its vote base across caste lines, by gaining support from diverse communities and parties – except the Muslims and a majority of the Yadavs.

In this period, the dejected Muslim vote slowly started drifting away from its secular pole to vote for its own. In the 2019 general elections, the AIMIM polled 27 per cent in the Lok Sabha seat of Kishanganj, and in 2020, it won five assembly seats.

But in June 2022, the RJD managed a quiet coup by getting 4 of the 5 AIMIM MLAs to defect to the RJD. In hindsight, that was perhaps the first step in the re-consolidation of the minority vote under a ‘secular’ MGB banner, and a planned precursor to Nitish Kumar’s departure from the NDA.

Fourth, this move makes sense, because the BJP is on a steady growth path in Bihar, and will keep attracting votes from the MGB and the ‘Others’. They have already absorbed all three MLAs of the Nishad community-based Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP) into the BJP.

Fifth, this return to vote banking by the MGB means that Bihar is finally opening itself up to a counter-consolidation. We’ve seen this happen in state after state since 2014: the more the secular parties attempt to consolidate the minority vote, the more it impels incensed Indians to rise above caste identities to vote for the BJP.

And, sixth, the transfer of votes between alliance partners takes place with remarkable efficiency in Bihar; party loyalties are strong enough to weather shifting alliances. But there are exceptions. In 2015, when the MGB consisted of the Congress, the RJD and the JDU, the BJP lost narrowly to the MGB in 25 seats by just around 2 per cent. This happened at a time when the BJP commanded a smaller vote base than it does now.

In 2020, when the BJP and JDU contested the elections together, Chirag Paswan and the LJP decided to leave the NDA – with a twist. They chose to put up candidates only against the JDU.

This decision had a curious outcome: in 25 seats contested by the JDU against the RJD, the LJP vote share was greater than the JDU’s losing margin, meaning that if the NDA alliance had remained intact, the JDU would have won around 70 seats, rather than the ignominious 43 they got (by corollary, the RJD would have won only 50 seats, instead of the 75 they got).

The point is that the events of 2015 and 2020 referred to above were phenomena which Bihar hadn’t witnessed previously. Their implications will be elaborated upon in two forthcoming pieces.

What does all this mean for the future of politics in Bihar?

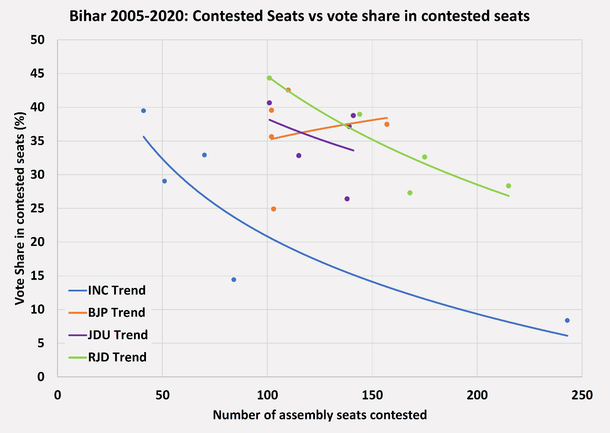

One, historical data shows that political parties follow a common pattern in assembly elections: the more seats they contest, the more they lose, and the lesser their vote share. The only exception is the BJP.

As a dimensionless cross-plot of contested seats versus vote share in contested seats (as distinct from a party’s state-wide vote share, which would be a lower figure because it also includes those seats they didn’t contest) below shows, an inverse correlation is irrefutably evident for the Congress (blue curve), the JDU (purple curve), and the RJD (green curve). Only the BJP (orange curve) shows a rising trend.

Two, in the next elections, therefore, the BJP will return its best performance in Bihar to date, provided Chirag Paswan of the LJP restricts his ambitions to reasonable limits and does not demand too many seats.

While it is simply too early to forecast whether this improvement will be a surge a-la-UP, or not, this much is clear: the BJP will gain votes from the JDU and ‘Others’.

Three, consequently, the ‘Others’ vote would be the lowest polled since the state’s boundaries were redrawn in 2000.

Four, the RJD will expand its vote base through a reconsolidation of the Muslim vote, and the return of the JDU.

As on date, it is expected to remain the largest party in the state, but without the ability to garner a simple majority on its own (Nitish Kumar will be wary, and ensure that the RJD contests on only around a hundred-odd seats, much like how the Shiv Sena managed to restrict the BJP in Maharashtra, in 2019).

Five, one intriguing unknown at present is the extent to which the Left parties will ally actively with the MGB. The Maoist CPI(ML)(L), encouraged by the 12 seats they won in 2020, would be eager to maintain that momentum, but their continued presence in the MGB would create a conflict of image for the Congress – particularly at the national level.

The BJP would milk the Congress’s association with the original ‘tukde-tukde gang’ for all it’s worth, hoist the bogey of ‘Urban Naxals’, and force the Congress to spend the next campaign explaining this alliance away. It will be interesting to see if the MGB is able to circumvent this very real perception issue.

Six, while the JDU will certainly add sizeable heft to the MGB’s vote base, the manner in which the LJD scuppered Nitish Kumar’s joy in 2020 teaches us that vote transfer from the JDU to the MGB will be both restrained, and uneven. The party’s performance will also be impaired by departures to the BJP. As a result, the JDU will get squeezed.

Seven, these developments will make the next Bihar elections more bipolar, and with a higher index of opposition unity. It is quite possible that the ‘Others’ vote share could dip below 15 per cent in the next assembly elections, and perhaps even less, in the 2024 general elections.

And, finally, eight: the probability of midterm assembly elections in Bihar seems low. The Chief Minister’s legendary tendencies for whimsical impulses will be tempered by greater survival instincts, the need for the MGB to find its feet (a euphemism for ‘you know what’, now that the RJD is back in government), and a harsh reality – that the JDU will not endure in its current form beyond one more election cycle.

Bottom line: in qualitative terms, the future electoral dynamics of Bihar will be a sum of ‘Muslim-Yadav’ vote banking redux, an inevitable counter-consolidation in favour of the BJP, increasing bipolarity between the BJP and the RJD, and the decline of the JDU. How that translates into Lok Sabha seat numbers remains to be seen.

(All data from Election Commission of India website)

Also Read: Bihar Politics: A Problem That Solved Itself For The BJP

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.