Ground Reports

Why Every Dog Lover Should Be Horrified By India's Stray Dog Crisis

Adithi Gurkar

Jul 11, 2025, 04:34 PM | Updated Aug 03, 2025, 09:46 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Across cities and towns, a ritual plays out daily. Few can ignore those soulful eyes, the hopeful tilt of the head, the gentle tail thumping against dusty streets. Many pause to share a biscuit, a bun, or simply a moment of quiet connection.

Over time, these free-ranging dogs have learned to play their part flawlessly, coaxing out sympathy, snacks, and even a fleeting sense of virtue from humans. Many devoted feeders carry official identification as Colony Animal Caretakers, certified by the Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI), formalising their role.

Yet beneath this heartwarming tableau lies a graver, bloodier reality.

On 15 January 2025, five-year-old Samreen Kouser became one of the many victim of India's escalating stray dog crisis, mauled to death by a pack in Jammu and Kashmir's Rajouri district. Her death added to a grim tally: 3.05 million dog bite cases reported in 2023 alone, resulting in 286 fatalities. Nearly 5,740 bites every single day across India. This tragedy, along with the deaths of two children in Delhi's Vasant Kunj in March 2024, briefly thrust the crisis into national headlines.

Behind these stark statistics lies a persistent question India has struggled with for over two decades: can a nation claim to protect animals while allowing them to suffer, and cause suffering, on its streets?

What makes these deaths particularly haunting is not their rarity, but their inevitability within our current system. Despite decades of well-intentioned sterilisation and vaccination drives, our cities and villages teem with millions of these canines, creating escalating friction.

The time has come for an uncomfortable truth. Are our current compassionate approaches truly serving the best interests of either humans or animals, or has our reluctance to consider more decisive measures trapped us in an unsustainable cycle demanding difficult re-evaluation?

Legal Framework

In India, stray dog regulation first found mention in the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (PCAA), 1960. This visionary legislation, which began as a private member’s bill introduced by renowned dancer and animal lover Rukmini Devi Arundale, made India one of the first countries globally to provide legal rights to domestic animals. The PCAA established the Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI) as an advisory body.

Yet beneath this noble origin lies a transformation that would likely have horrified its founder.

"The AWBI, which is supposed to be a mere advisory body, has progressively radicalised over the last 15 to 20 years, influenced by foreign NGOs such as PETA," Meghna Uniyal, Director and Co-founder of the Humane Foundation for People and Animals, tells Swarajya. "For instance, if a concerned citizen complains about stray dogs, the AWBI will actually send them a threatening letter. Where does the board get this authority from?"

The philosophical shift runs deeper. "While the intention of the PCAA was to prevent wanton cruelty, it allows for the usage, management, and killing of animals. But the Animal Welfare Board has now become an animal rights organisation. If a country were to embrace animal rights in the fullest sense, pest control would not exist, dogs would have to be granted the same rights as humans, and humans would have to cease being carnivores," Uniyal adds.

The original PCAA held clear moral boundaries, explicitly prohibiting abandoning animals and defining an owner as "not only the owner but also any other person for the time being in possession or custody of the animal," making it an offence for anyone, including municipal authorities, to abandon them.

Four decades later, however, a bureaucratic sleight of hand would unravel this framework.

In 2001, the Ministry of Culture, then headed by Menaka Gandhi, an organization with no association with animal welfare or regulation, issued the Animal Birth Control (ABC) Rules 2001. These rules were revised again in 2023 and notified by the Ministry of Fisheries and Animal Husbandry, creating a jurisdictional maze that would confound even seasoned administrators.

The most crucial provision reveals the policy's fundamental contradiction: while local authorities can sterilise and immunise street dogs, "after surgical sterilisation, the dogs shall be released at the same place or locality from where they were captured."

By its own admission, the ABC rules require the release of the very dogs that are biting people, creating nuisances, or posing dangers in the first place.

This has effectively legalised the continued growth of ownerless dog populations, unlawfully superseding both local laws and the PCAA while empowering Colony Animal Caretakers against citizens and Resident Welfare Associations who oppose indiscriminate feeding.

"The 2023 amendment doubles down on the problem and mandates the maintenance of stray dogs in gated premises as well, including hospitals, schools, airports, markets and residential areas. So, while the problem is stray dogs on streets and gated premises, the solution, according to the AWBI, is again stray dogs on the streets and gated premises, even after they kill or attack citizens," Uniyal laments.

International best practices consistently identify food source elimination as the primary control mechanism. However, the AWBI advocates public feeding of stray dogs, transforming a serious public health concern into a policy that promotes population growth.

Among the diseases these animals spread, rabies and distemper are most lethal. With 18,000 to 20,000 rabies deaths annually, India has earned the dubious distinction of being the rabies capital of the world.

The environmental consequences paint an even grimmer picture. The US Environmental Protection Agency classifies canine waste as a hazardous pollutant, comparable to automotive chemicals. Waste from just 100 dogs over 2–3 days can contaminate water bodies up to 20 miles.

This creates a stark policy contradiction in India: while pet owners are legally mandated to collect their animals' waste, an estimated 60 million free-roaming dogs deposit approximately 30,000 tonnes of pathogen-laden feces on public streets daily, creating substantial public health risks.

A haunting question emerges from this maze of good intentions and devastating consequences: how did a nation once hailed as a pioneer in animal welfare end up trapped in a system that safeguards neither human safety nor true animal wellbeing? And more urgently, in our pursuit of appearing compassionate, have we built a bureaucratic machine so distorted that it now fails the very citizens it was meant to serve?

Numbers Do Not Add Up

The AWBI's ABC programme guidelines clearly state that obtaining reliable population estimates is essential for determining resource allocation and evaluating intervention success. Despite allocating substantial funding over many years, the AWBI has admitted through RTI requests that it maintains no systematic records of vaccination rates, rabies incidents, sterilisation procedures, or dog bite cases.

This represents staggering institutional failure. Billions of rupees have flowed through a system that cannot account for even its most basic performance metrics.

The institutional amnesia runs deeper than record-keeping failures. Government assessments in 1999 and 2008 by the Ministry of Environment and Forests revealed that implementing agencies lacked reliable demographic data on stray dog populations. Two decades later, ABC programmes still operate without adequate data collection.

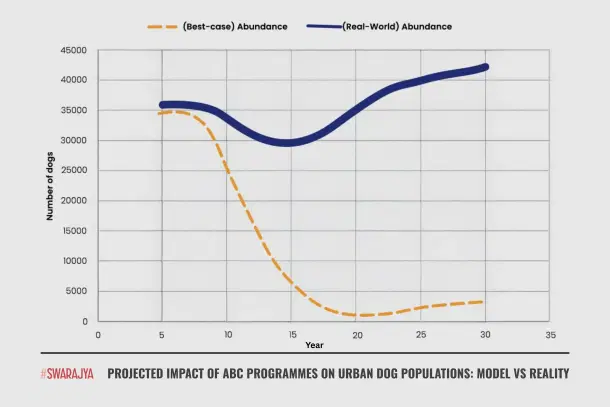

Research by Aniruddha Belsare of Emory University and Abi Tamim Vanak from ATREE examined resources needed for effective population reduction. Their findings showed that maintaining sterilisation rates at approximately 90 per cent of the total population for a minimum of ten years is necessary to achieve meaningful population reduction.

The DogPopDy model simulates real-world constraints, including limited catchability and continuous immigration of new dogs. Under realistic conditions, even intensive efforts involving 750 sterilisations monthly prove ineffective at reducing overall population numbers.

Annual population replacement rates in free-roaming dog communities reach approximately 40 per cent, with breeding-capable animals rapidly compensating for reproductive loss. Roughly half the dogs sterilised die within a year of natural causes, rendering these expensive interventions effectively futile in long-term control.

Dr Debottam Bhattacharjee, a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Centre for Animal Health and Welfare, City University, Hong Kong, adopts a conciliatory approach: "Dogs exist no more in number in our ecosystem than crows, and all have different personalities — some docile, some aggressive. A better approach would be identifying problem dogs that are aggressive, territorial, or diseased, then selectively rehoming or euthanising them rather than attempting to address all strays."

"Otherwise, it would be an impossible endeavour to rehome or euthanise all stray dogs in India. The number is too huge, and the exercise would prove to be very expensive as well. Neutering dogs itself brings down their aggression level to a large extent, thanks to hormonal changes,” he argues.

Ms Meghna Uniyal remains deeply sceptical: "Sterilisation does not address the core problems of attacks, diseases and accidents associated with stray dogs. While marketed as humane, dogs often end up mutilated from botched surgeries and are simply abandoned on streets to fend for themselves."

Dr Neeraj Mahar, Project Scientist at the Wildlife Institute of India, echoes similar concerns: "It becomes a very cumbersome exercise and eats up a lot of resources, with limited results."

In our search for solutions that satisfy both our humanitarian impulses and practical constraints, we may have created a policy ecosystem so compromised by competing objectives that it serves neither human safety nor animal welfare. Both species remain trapped in a cycle of conflict and suffering, the product of good intentions married to flawed implementation.

The Psychology of Blame

Beneath these logistical debates lies a more complex question: how much of the aggression shown by strays can be attributed solely to the dogs? Are they simply mirrors reflecting our own humanity or lack thereof?

Two schools of thought emerge when examining canine aggression. One suggests that domestic dogs, descended from wolves, retain an innate ferality within their genetic makeup, a primal wildness that no amount of human interaction can fully suppress. The other, championed by behavioural researchers, offers a more nuanced, perhaps hopeful, view.

Dr Debottam Bhattacharjee explains how human attitude shapes canine conduct: "Our research pointed to a remarkably optimistic conclusion. Mutual behaviour shapes interspecies relationships. Being 'nice' or 'positive' towards dogs may result in significantly less conflict with unknown humans. In simple words, if a dog consistently receives negative actions from humans, such as being beaten, it is highly likely to react accordingly when encountering an unknown human."

His research methodology reveals fascinating patterns: "We defined the study according to habitats in three categories: high human flux, intermediate human flux and low human flux zones. The high flux areas were places like bus and railway stations, markets, and other crowded locations. Intermediate zones were a mix of residential and commercial areas, like apartments alongside restaurants and shops. Low flux zones were purely residential," he explains.

"It was surprising to find that dogs were friendliest and most social in the intermediate zone. This is probably because more people tend to offer food and be kind towards them," Bhattacharjee continues, his findings suggesting that canine temperament is highly sensitive to the quality of human interaction.

Yet this hopeful narrative clashes with a harsher reality, as Ms Uniyal points out: "There are many problems with such a premise. Dogs are domestic companion animals, meant to be under human supervision and control. Numerous studies show dogs can be triggered by a range of factors: fear, territoriality, sudden movements, breed characteristics. Pets, even when well cared for, can bite their owners or neighbours."

She continues: "If domestic animals such as dogs are kept forcefully on the streets, conflict is inevitable. Dogs will chase and bite. Because that is what they do. Blaming human behaviour does not explain the million unprovoked dog attacks reported each year. Of course, cruelty exists, but the solution to that is not allowing dogs to roam the streets while blaming the public for the resulting consequences."

Both perspectives contain uncomfortable truths.

Can public policy realistically assume that 1.4 billion Indians will consistently demonstrate the patience and empathy required to reduce canine aggression?

And if human behaviour is indeed the primary driver of dog aggression, what does this reveal about a system that continues to place both species in situations almost certain to generate conflict?

The Silent Ecological Catastrophe

While India grapples with the human toll, another tragedy unfolds in forests, mountains and grasslands.

"After habitat loss, dogs happen to be the second-largest threat to wildlife in India," Ms Uniyal reveals. In an IUCN study, dogs, cats and rodents were identified as the most damaging invasive species globally for wildlife.

"When dogs are allowed to be free-roaming, they turn feral. Their effects are multifold: harassment, attacks where they kill other animals, spread of diseases, killing juveniles and plundering of nests," Ms Uniyal states.

Dr Sumit Dookia, Associate Professor of Animal Ecology and Wildlife Biology, offers sobering perspective: "For centuries, a dog has been thought to be a good human companion and evolved from wolf to the modern-day dog. They are basically facultative carnivores as well as scavengers. By anatomy and physiology, they are hunters."

The image of snow leopards, those magnificent ghost cats of the high Himalayas, falling victim to packs of feral dogs strikes at something profound in our understanding of natural order. These are not the clean kills of natural predators maintaining ecosystem balance, but the chaotic violence of domestic animals reverting to primal instincts in landscapes they were never meant to inhabit.

"I have personally seen many times how these dogs hunt wild herbivores. These dogs form packs and behave like wolves. This is being reported all across the subcontinent. Genetically, they have almost all the traits of their ancestors (wolves), and surprisingly, in the last 8–10 years, there are many areas where these dogs have been seen mating with wolf packs (Tibetan wolf as well as grey wolf) in the wild."

The genetic implications carry consequences beyond immediate predation. Abhi Vanak explains: "In such cases, the wolf genome gets diluted because of the incursion of dog genes into wolf genes. This is problematic because the domestication process has incurred several changes in their morphology like weaker jaws, smaller bodies and skulls. When these changes are passed on to wolves, it affects their ability to survive in the wild."

When Paradise Becomes Predatory

In Ladakh's fragile ecosystem, the collision between compassion and conservation reveals itself with devastating clarity.

Dr Neeraj Mahar's research maps canine-wildlife interactions: "In Leh, free-ranging dogs impact peripheral species such as foxes. In Hanle and Changthang's semi-urban wetlands, shepherd dogs pose a threat to black-necked cranes, bar-headed geese and greylag geese."

The devastating statistic: "The black-necked crane is listed as near threatened by the IUCN. Only around 100 visit Ladakh, with 20 breeding pairs."

Twenty pairs. These majestic birds now risk extinction due to dogs. "Argali also face threats from stray dogs. Since dogs are scavengers, they compete directly with natural scavengers such as vultures, foxes and wolves, often overpowering them by sheer numbers, with packs of 10 to 15 dogs."

"Scat samples revealed feathers and fur which is evidence of ducks, sparrows, pheasants, and even blue sheep and kiang being consumed by the strays."

The most tragic element is spiritual: "Ladakh is overwhelmingly Buddhist. Over the past 20–30 years, influenced by the Dalai Lama's message of compassion, many have adopted vegetarianism and ceased hunting. The same compassion now extends to dogs, leading locals to oppose euthanasia even after dog attacks on humans."

Dr Dookia outlines the government's response: "In the last tiger census, more dog photos appeared on camera traps than tigers. You can imagine how they reached into core tiger habitats. The National Tiger Conservation Authority finally had to release a SoP to deal with these uncontrolled dogs."

Ms Uniyal is direct: "Policy currently mandates that dogs inside protected areas can only be sterilised and released just outside. You have 80 million stray dogs. Not an endangered species, yet they are prioritised over a few hundred black-necked cranes and less than 100 great Indian bustards."

The Politics of Extinction

Ms. Uniyal's critique extends beyond policy to the very nature of the advocacy driving these decisions: "The same NGOs that cry for them, don't want to take care of them or shelter them. Their involvement is restricted to twice a day going and throwing food at them and that's about it. Due to such policies, and the menace these stray dogs have become, we have created a situation where people who were generally neutral or had no particular opinion about these dogs, today hate them."

Dr Mahar's assessment reveals the David-and-Goliath nature of this battle: "It has become very politically charged. The wildlife lobby is a very small community when compared to the dog lovers' lobby. We do not have that many voices or resources. There is a lot of ignorance and lack of awareness as well."

The argument that street dogs represent indigenous Indian breeds worth preserving reveals intellectual dishonesty.

"First, if your intention is to save the species, then why are you neutering them? Should you not instead breed them? Second, indigenous Indian breeds have already been documented, be it Caravan hounds, Mudhol hounds or Kombais. They look very different from stray mongrels. Interbreeding over many generations has led us to this brown-looking dog that is no Indian breed. So to equate mongrels to Indian breeds is just bizarre," Ms Uniyal argues.

What Global Success Reveals About India's Failure

India's approach to stray dog management stands as a monument to wilful blindness. A nation that has chosen to ignore the very solutions that lifted entire continents out of similar crises. The contrast is not merely stark; it is damning, revealing the chasm between what works and what we pretend might work.

Dr Dookia's description of American wildlife management reads like a dispatch from a parallel universe:

"In the US, stray dogs in or near wildlife habitats are captured using humane traps and either rehomed or euthanised if aggressive or diseased. Additionally, wildlife reserves often have perimeter fences or buffer zones to prevent entry of dogs and other intruders."

Ms Uniyal's revelation about America's annual reality carries the weight of institutional honesty that India seems incapable of embracing:

"In America today, in 2025, 2 to 3 million dogs and cats will be euthanised every year. They just do not become stray because they are not allowed to live on the streets. Until human beings own dogs and cats, there will always be a surplus, there will always be irresponsible ownership, there will always be too much breeding. These surplus animals are going to end up in shelters or on the streets. The difference between us and the developed world is that we just have them on our streets."

Ms Uniyal's analysis reveals a disturbing pattern that should shame every postcolonial democracy:

"The focus of organisations like PETA is on the developing world because it is simpler to do things like equating human beings with dogs, or to reduce the value of human lives. It is very easy to get away with this kind of treatment in the developing world. PETA is not doing the same in America or in any developed country. They are saying it to your face: your life and the life of a dog are the same, and we are somehow expected to feel very happy about this."

It is a form of ideological imperialism that trades on India's post-independence eagerness to appear progressive, even when that progressivism serves neither human nor animal welfare.

The hypocrisy cuts deeper when one considers the lived realities. American children walk safely to school while Indian children face daily threats of mauling. American wildlife thrives in protected habitats while Indian species face extinction from abandoned pets. Yet somehow, India's policies are presented as more humane, more enlightened, more worthy of international praise.

Abhi Vanak's research into historical precedents reads like a blueprint for success that India has chosen to ignore. The Japanese model offers a masterclass in coordinated public health intervention: comprehensive vaccination paired with systematic removal of unowned animals. The results speak with the clarity of mathematical proof — rabies eliminated, dog populations controlled, public safety restored.

Vanak's additional insight from Osaka prefecture reveals the speed with which decisive action can transform entire regions:

"Indeed, in the Osaka prefecture, the first epidemic between 1914 and 1921 was controlled wholly through the leashing of pet dogs and the removal of unowned dogs."

Seven years from epidemic to elimination — a timeline that makes India's decades of policy paralysis appear not merely ineffective but actively negligent.

"Stray dog and disease control is a science which has been studied and successfully implemented across the world. Rabies has already been eradicated from many countries. This has largely been due to a zero tolerance policy for stray animals. In India, we do not necessarily have to reinvent the wheel," Ms Uniyal laments.

Her analysis of India's existing legal framework reveals the ultimate irony:

"In India, dog population control has been written very clearly in the relevant legislation at the central, state and municipal levels and even in the BNS. They all clearly lay out the same principles that are being followed globally. Every stray animal has to be removed from the streets. Domestic animals such as dogs and cats can be either sheltered, rehomed, or humanely euthanised. There is really no other way to tackle this problem."

The solutions exist, codified in law, tested by experience, proven by results. Yet they remain unimplemented, overridden by rules that have no legal authority but tremendous political power.

"In the legal hierarchy of things, rules are at the very bottom. They are only meant to further an Act. They cannot change the premise and create entities like 'street animals' or 'community animals'. The solution is very simple. Scrap the ABC rules. They have no role to play when it comes to public safety, health or animal welfare. If you force animals to be homeless, there will be instances of cruelty, there will be accidents and there will be retaliatory attacks," Ms Uniyal concludes.

Adithi Gurkar is a staff writer at Swarajya. She is a lawyer with an interest in the intersection of law, politics, and public policy.