Science

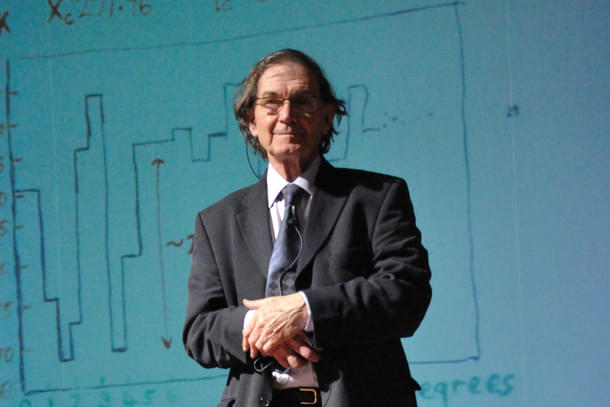

Sir Roger Penrose: Bridging The Worlds Of Mind, Mathematics, And Mysticism

Aravindan Neelakandan

Dec 29, 2024, 01:24 PM | Updated 01:34 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Sir Roger Penrose, a name synonymous with genius, has tirelessly pursued the secrets of the universe with the fervour of a true renaissance seer. His intellectual contributions span a breathtaking range, from the intricate beauty of Penrose tilings to the vast expanse of cosmology, and even the enigmatic depths of human consciousness.

Mathematics, his chosen tongue, serves as the key to unlocking the mysteries of existence, to glimpsing the proverbial mind of God. Yet, beyond the towering intellect and the manifold genius lies a man, a human being navigating the complexities of life.

‘Impossible Man’ by science writer Patchen Brass delves into the very essence of this remarkable individual, exploring the facets of Roger Penrose that are inextricably intertwined with his relentless pursuit of truth, beauty, and order. It is a journey into the heart of a man whose life has been an odyssey of extraordinary fascination.

It shows the trajectory of the development of a mind like that of Penrose, right from his childhood when he was fascinated by geometry to the unfolding of his genius and the price he constantly had to pay — a loneliness that shall accompany him forever.

Early on Penrose as a child tricks his nanny Stella who insists that he should eat the greens making them into a semicircle to make her believe he had eaten them. Trivial. But here is a connection Penrose would later make between the realm of the physical, the psychological and the mathematical geometry. But when he and his family used to listen to astrophysicist Fred Hoyle’s lectures on BBC radio, Barss writes:

When listening to Hoyle or talking to Lionel or Oliver, Roger’s senses stretched in every direction, to the planets, stars, and galaxies, back to before Earth existed, and forward to long after it had disappeared. He noted the fraction of a second between light’s bouncing off the faces of his family members and hitting his own retinas and the slightly longer fraction of a second before his brain became aware of that perception. Nothing happened when or where it seemed.p.42

Just opposite this page is the light cone diagram made famous in public consciousness through Stephen Hawking's ‘A Brief History of Time.’ However, the passage written through various interviews and interactions with Penrose clearly reveals an epiphanic experience that Penrose underwent in understanding science through such pop-science lectures.

One wonders if the neural circuits that got excited inside the kid Roger’s brain, were similar (not the same) to the ones that were excited when a young boy saw the white cranes against the dark rain clouds amidst the green expanse of paddy fields in Kamarpukur.

Communicating science not as an explanatory answer but as a wonder-triggering process to a child’s mind can take it to soar into very high altitudes — whether it is science, art or mysticism. Of all persons, Richard Dawkins, the ace atheist points this out in his book ‘Unweaving the Rainbow’ where he says thus:

The impulses to awe, reverence and wonder which led Blake to mysticism (and lesser figures to paranormal superstition, as we shall see) are precisely those that lead others of us to science. Our interpretation is different but what excites us is the same.Unwaving the Rainbow, p.17

These chapters of the book — that deal with the formative influences on Penrose — are thus important for our pedagogy framers.

Of particular interest shall be the fourth chapter which deals with the ‘impossible’ structures that Penrose came up with in the 1950s. The chapter vividly narrates how Penrose was intimidated rather than excited by mathematics at the International Congress of Mathematics in Amsterdam where he attended a Fields medal — the highest honour in Mathematics and often called the Nobel Prize of Mathematics — presentation ceremony.

He was pursuing his PhD and was totally left alone amidst all the mathematical talk that left him bewildered. He exited the entire building and chanced into ‘an exhibition at the Municipal Museum of Amsterdam’ where he had an encounter with the lithographs of Dutch artist M C Escher. That should have been the Arjuna-meet-Krishna moment for Penrose. Barss writes:

Escher’s prints amazed Roger. He had never seen anything so clever, so beautiful, so surprising and delightful. They were realistic and impossible at the same time. Escher played with perceptions of up and down, foreground and background, scale and dimension. The images were a revelation, yet also deeply familiar, as though the artist had reached into Roger’s own mind to pull out these ideas…. The image made powerful sense to him. Escher spoke in a visual mathematical language Roger understood fluently.Impossible Man, p.59

Penrose took the catalogue of the lithographs to his father Lionel, a famous psychiatrist in his sixties, as excited as Penrose and inspired to create the now very famous impossible structures — Penrose triangle and Penrose stairs. Roger also had the opportunity to be equally inspired by another great mind Paul Dirac the physicist and one of the pioneers heralding New Physics. Barss writes:

Dirac’s lectures on quantum mechanics affected him just as profoundly. At smaller and smaller scales every physical property seemed to disappear: colour, temperature, pressure, conductivity, elasticity. These characteristics gave way to deeper, more fundamental properties. Ultimately, the only things that remained were numbers and equations. Mathematics underlay it all.p.62

Along with these, Penrose also confronts Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorem which shows ‘how every logical system generates statements that are true but that cannot be proven within that system.’ This gave him a glimpse of the problem of consciousness says Barss.

The book very lucidly travels into the scientific pursuit of Penrose. Barss introduces concepts and tackles the challenge of presenting in a non-technical language the complex challenges which Penrose encountered voluntarily in his pursuit of mathematical beauty in explaining the deeper realities of space and time, matter and energy. Here is a sample:

Traditionally, scientists use a mathematical tool called a Fourier transform to deconstruct a complicated wave pattern into simpler constituent parts, allowing them to understand the relationship between, say, a particle’s position and its momentum... Roger wasn’t satisfied with Fourier transforms. They weren’t simple or elegant enough for him. They involved too many equations. He could already see a simpler alternative: the Riemann sphere. Mapping the wave equations of quantum field theory onto the complex coordinate system of the Riemann sphere reduced the calculations required to separate amplitudes and turned an algebraic challenge into simple, beautiful geometry.p.81

The book also reveals another great mental faculty of Penrose. There has been an intense debate in the circle of international physicists regarding the nature of Quasars or Quasi Stellar Objects. These objects had so much energy packed into a very small space that they suggested singularity. Penrose got interested in this and immersed himself in it. Barss writes:

The quasar conundrum sparked Roger’s geometric creativity and his instinct for unexpected simplicity. Since his days making perpetual calendars and moon clocks, he had gravitated toward underlying principles and universal structures. He didn’t want to find some outlandish set of circumstances under which a singularity could form. He wanted a general rule with no need for idealized circumstances.p.120

Meanwhile, Soviet physicists Lifshitz, Khalatnikov, and Belinsky studying the same Quasar data declared that singularity as envisaged by Penrose was more a mathematical conjecture than a reality, they argued that in any situation approaching a singularity, the chaotic nature of massive bodies and gravitational fields would not form a real singularity. The scientific community at large was inclined towards Lifshitz et al. Penrose intuitively knew that singularity was real and Soviet physicists should have made a mistake. He immersed himself in the problem.

The whole passage is worth quoting because it shows how highly sharpened by intense mathematical logic and scientific contemplation finally emerges as an intense visualisation which then in turn maps into mathematical formalism:

In the brief silence of that street crossing, Roger’s mind shot out again across billions of light years to the screaming hot mass of C3 273. He saw it as he had never seen it before. It might have begun as an amorphous dust cloud, a collapsing galaxy, or even a galaxy cluster. Its origins didn’t matter to what happened next: gravitational collapse had taken over, pulling all the matter deeper and closer to the centre. Like a twirling figure skater pulling their arms in close to their body, the mass spun more and more quickly as it contracted. As it shrank, it created a heat so intense that radiation blasted out on every wavelength in every direction. The smaller and faster it got, the brighter it glowed. But there was more. Roger’s imagination worked in four dimensions, not three… In that moment, he saw the thing almost nobody else believed possible: every light ray, every spatial vector, even the arrow of time itself converged on a single point. They all came to a halt. Density and space-time curvature went to infinity. Relativity broke down.p.123

Thus, was born his 1965 paper ‘Gravitational Collapse and Space-Time Singularities.’ Published in the journal Physical Review Letters, it was only three pages long and was more a geometric approach than algebraic. The paper was resisted and debated because the general scientific consensus then favoured Lifshitz et al. It was for this paper mainly that Penrose would be awarded the Nobel Prize, 55 years after its publication!

The Soviet physicists while opposing Penrose externally, started re-reading their own paper. They found that it contained an error. Lifshitz wrote a paper confessing to the error. They did not want someone else pointing it out. The paper had to be smuggled out of the Soviet Union with name of the author removed. Then it was published in the West.

Barss also discusses the relationship and collaboration of Penrose and Stephen Hawking. Hawking built upon the work of Penrose and extended it to cover the origin of the universe. Soon the work was known as Penrose-Hawking Singularity theorems. Roger had some reservations about sharing the name because the original theorem of Penrose was a revolution and what Hawking did was a refinement. But when Hawking’s medical condition was getting known, Penrose never went public with his dissatisfaction.

Then there is his collaboration with Stuart Hameroff and their theory of ‘orchestrated objective reduction’ of consciousness. It was a collaboration that made many of Penrose’s academic friends very worried. But Penrose stood by his collaboration with Hameroff even though he did not agree with all his worldview. Barss writes:

Roger understood microtubules about as well as Stuart understood noncomputable quantum systems. Each saw in the other validation for ideas they wanted to be true. They emboldened each other.p.206

The book reveals a lifelong obsession Penrose seems to have with finding a very human muse and the way he projects it on women who get close to him with disastrous results. This may actually open up an important domain for a challenging Jungian study of how genius works and the underlying expressions of Anima or Animus.

The readers even meet a Jungian psychologist in the book. Throughout his life, this search has led him to broken relations. Often, he requested the women he moved closely with or he worked with to be his muse. This actually intimidated the women making them feel reduced from being an individual in their own right or as in the case of a theoretical physicist who worked with Penrose late in his career, extremely angry that she cut all her connections with him. He had to plead with her and apologise, and they started collaborating again. Finally, Penrose lets go of his muse fantasy we are told.

But was it just a fantasy? Here one should remember that Penrose was a man of 'incredible intuition.' Barss quotes his early colleague Wolfgang Rindler saying this about this faculty of Penrose:

Roger Penrose is a master in skipping all the mathematics. I had to do all the stuff in between. Roger has this incredible intuition. I have a little bit of that in physics but not in mathematics. It’s a very different kind of intuition. It always bothered me that I didn’t have it in mathematics. He had the intuition of what has to be true. I could prove it, but I couldn’t intuit itpp.88-9

Indian readers will at once connect this quality of Penrose with that of Srinivasa Ramanujan. Penrose was born eleven years after Ramanujan died. But Ramanujan had his divine Muse — Namagiri Thayaar — which is essentially integrated inside the self — within.

Coming from a Christian and secular environment, Penrose had to search for the muse outside, projecting it onto every woman who showed the capacity to understand him or collaborate with him, as said often with miserable consequences for both.

On the whole, the book is an exciting journey into the inner workings of a fellow human being who is a genius gifted to provide us with a vision of the most guarded mysteries of the universe through the language of mathematics which in turn attained poetic beauty of the highest order.

He is a person who could visualise the beauty of that language in geometry and through that language he explored and experienced the universe — from singularities and black holes to the mystery of consciousness.

He connected the three realms of the universe: the physical realm, from which emerged the mental or psychological inner universe, and from that, the mathematical universe. However, only a small fraction of the rules of this mathematical universe gave rise to the physical universe. Thus, to him, the three realms are interconnected.

He has the ability to move through all three realms, and this book takes us on an inspiring journey, offering glimpses of what he must have experienced. Even these glimpses are profoundly humbling and elevating.