States

Rajasthan’s Rs 17,000 Crore Question: How Many Districts Are Enough?

Ankit Saxena

Jun 03, 2025, 11:21 AM | Updated Aug 03, 2025, 09:47 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

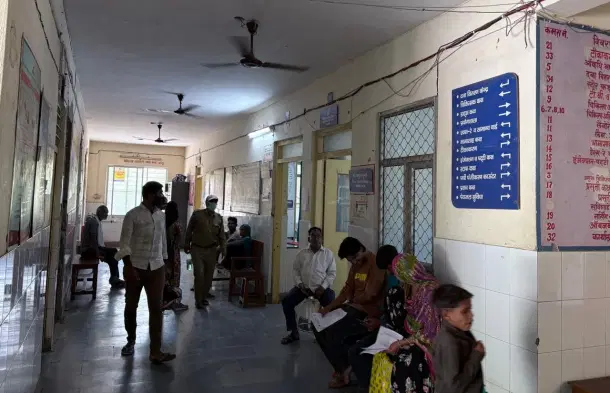

A government-run satellite hospital in Khairthal, Rajasthan, was allotted facilities in February to provide dialysis treatment. Since then, it has been treating an average of 40 to 50 patients each month.

Forty-five-year-old Phool Singh, from a village 25 km away, is among those who now receive treatment at the facility. Until last year, however, he had to travel more than 40 km to Alwar for each session. For many like Phool Singh, this hospital has been a helpful step forward for healthcare in the region.

Dr. Nitin Sharma, Principal Medical Officer (PMO), Khairthal-Tijara, told Swarajya, "Earlier, patients like Phool Singh had to go to Alwar or other regions, more than 70 km away, for dialysis. That was just the travel. Then came the time and process of dialysis itself, which had to be done regularly."

"This facility is now convenient for patients as well as for the healthcare system of the region," he added.

Khairthal is located in southwest Rajasthan and is now the district headquarters of the newly formed Khairthal-Tijara district. While the program itself was launched in 2019, it reached Khairthal in 2025, as the region only recently received the status of a separate district.

Behind Phool Singh's shorter journey lies a much larger question that has consumed Rajasthan for two years: In a state covering over 3.4 lakh sq. km, how many administrative districts are enough?

This seemingly simple question has sparked a remarkable experiment in governance—one that has seen Rajasthan's district map redrawn twice in two years, affecting millions of lives and billions of rupees in the process.

Historical Baseline: The Conservative Answer

To understand the magnitude of recent changes, it's important to grasp how district creation traditionally worked in Rajasthan.

Rajasthan is India's largest state by area and covers over 3.4 lakh sq. km, stretching about 869 km from east to west and 826 km from north to south.

Before its formation as a unified state in 1956, the region was known as Rajputana, with 19 princely states, the union territory of Ajmer-Merwara, and three small chiefships, Kushalgarh, Lava, and Neemrana.

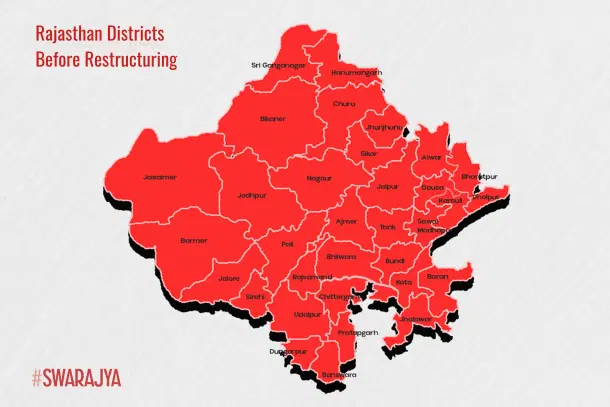

Following unification, Rajasthan began reorganising its internal districts. Considering the vast area, the formation of new districts has always been under discussion. Between 1956 and 2008, seven new districts were created.

This process was methodical and committee-driven. Dholpur was formed out of Bharatpur in 1982. In 1991, Baran, Dausa, and Rajsamand were formed from Kota, Jaipur, and Udaipur respectively. Hanumangarh was formed in 1994 from Sri Ganganagar. In 1997, Karauli was formed based on the R. S. Kumat Committee's recommendations.

The last district added before the recent upheaval was Pratapgarh in 2008, which was carved out of Udaipur, Banswara, and Chittorgarh during Vasundhara Raje's first term as Chief Minister.

Under Raje's government, in 2014, a committee was formed called the Parmesh Chandra Committee, which recommended four more districts, namely Balotra, Beawar, Deedwana, and Kotputli. But no immediate action was taken.

For over half a century, this pattern held: careful committee deliberations, gradual expansion, cautious implementation. Seven new districts in 52 years represented the conservative answer to "how many is enough?"—add districts sparingly, only when absolutely necessary.

Revolutionary Experiment: The "Bold Enough" Answer

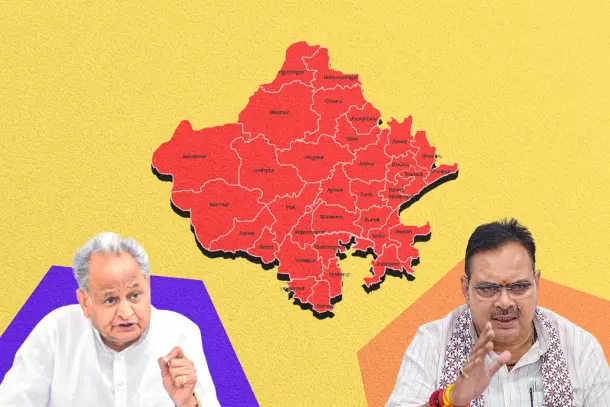

But in 2023, this decades-old pattern of cautious expansion was about to be shattered. The Congress government under Ashok Gehlot looked at Rajasthan's vast geography and persistent administrative challenges and reached a radically different conclusion: if gradual change hadn't solved the distance problem, perhaps dramatic transformation would.

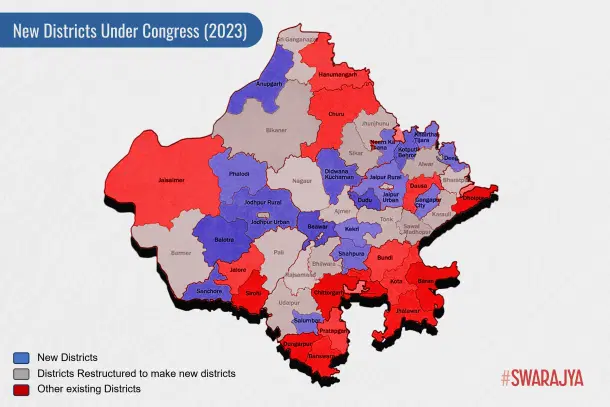

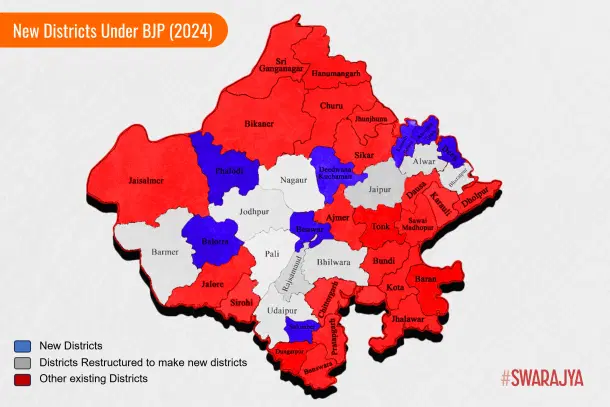

In March 2023, the previous Congress government, led by CM Ashok Gehlot, announced the creation of 17 districts with the aim of making administration easier. With this move, Rajasthan's total number of districts rose from 33 to 50.

This wasn't just an expansion—it was a complete rejection of the conservative approach. In one announcement, Congress created more than double the number of districts that had been formed in the previous 52 years combined.

This decision was based on the recommendations of a committee led by retired IAS officer Ramlubhaya.

The 17 new districts announced in 2023 were Anupgarh, Balotra, Beawar, Deeg, Didwana-Kuchaman, Dudu, Gangapur City, Kekri, Kotputli-Behror, Khairthal, Neem Ka Thana, Phalodi, Salumber, Sanchore, Jaipur Rural, Shahpura, and Jodhpur Rural.

The logic seemed compelling. Officials at the newly established district magistrate's office told Swarajya, "When these regions were part of Alwar, most areas were nearly 90 to 100 km from the district headquarters. It was very difficult for those people to keep going there for any work."

"Also, all development for this entire belt under Alwar was concentrated in Bhiwadi, due to its proximity to Delhi. Now, the district will have a dedicated budget."

Beyond healthcare, people expect gains in governance, budgetary allocation, infrastructure, and greater attention to the region. The revolutionary approach promised to bring government closer to people by dramatically multiplying administrative centers.

But as ambitious as this vision was, it was about to collide with practical realities that would test whether "bold enough" was actually "too much."

Reality Check: When "Enough" Becomes "Too Much"

The problems emerged almost immediately. This bold move soon ran into controversies and confusion. While many people welcomed the change, others felt the process caused issues with boundaries, offices, and staffing.

The sheer scale of the undertaking became apparent when officials calculated the costs. Whenever a new district is announced, major infrastructure development takes place, including administrative buildings like the district headquarters, court, and offices for agriculture, education, health, and the district council.

"It costs about Rs 1,000 crore on average to develop a district. In some cases, up to Rs 500 crore may be spent just on building offices," Lalit K Panwar tells Swarajya.

This would have added up to a budget of Rs 17,000 crore for the state, a necessary expense to prevent administrative and logistical problems, which were already emerging with the previous decision. This was one of the key reasons to reconsider the number of new districts.

The financial burden was just one problem. The administrative reality was even messier. "One major issue was poor planning and implementation. Many of the new districts faced serious administrative challenges, shortages of staff, and no proper office infrastructure," an official from a new district office adds.

The gaps between promise and reality became starkly visible on the ground. It was earlier reported that only 17 out of 52 government departments were functional in Khairthal. While there has been some progress in the infrastructure, the number of departments has only gone up to 18, according to the collectorate.

Many departments still operate from rented buildings or makeshift rooms. "Some were even working from parking spaces below, since there were no rooms allotted," an official tells Swarajya.

"Many departments do not yet have dedicated offices or full staff, and some still run from their old setups."

Though Collectors and SPs have been appointed, they work with limited resources, and there are ongoing border disputes between districts.

The revolutionary experiment had revealed a harsh truth: creating districts on paper was easy; making them function was enormously complex and expensive.

The "Data-Driven Enough" Answer

The 2023 Assembly elections brought a change in government—and a new approach to the district question. With the change of state government in December 2023, BJP CM Bhajan Lal Sharma set up yet another committee, led by Lalit K. Panwar, to review the earlier changes.

But rather than pursue another ideologically-driven approach, the new government opted for what it called a scientific method.

"From 1956 to 2008, Rajasthan added seven new districts, however, the Congress government in one go announced 17 districts. The first decision itself raised many questions," a senior official from the committee tells Swarajya.

The Panwar committee spent months conducting field visits and data analysis. They visited 14 of the 17 new districts and reviewed them based on 10 key parameters that took into account both the ground realities and the future needs of the region. These were:

- Geographical location/situation/boundaries/compactness

- Population

- Administrative structure

- Distance of the farthest tehsil from the district headquarters

- Effective law and order/governance

- Disposal of pending campaigns/schemes

- Backwardness of the region

- Availability of basic facilities and services

- Consent of the concerned existing district committees and tehsils

- Public sentiments/cultural harmony

To avoid arbitrary decisions, the committee anchored their analysis in comparative data. To set a benchmark, national-level data was used. With 788 total districts in India, the average population per district in India is about 23 lakhs, and the average area is 4,212 sq km.

Further, for the administrative structure, the average number of tehsils is 7.2, development blocks are 9.2, and villages, 900.

"In contrast to the national parameters, in Rajasthan, the average district size was much larger: around 10,000 sq km. Population density also varies. In desert districts like Jaisalmer and Barmer, it ranges from just 10 to 45 people per sq km, while in districts like Dholpur and Bharatpur, it can go up to 273 people per sq km."

Recognizing Rajasthan's unique geography, Panwar adds, "For the state, population thresholds were set at 9.5 lakh for general areas, 6 lakh for desert regions, and 4 lakh for tribal areas."

The committee also considered cultural factors that pure data couldn't capture. Panwar tells Swarajya, "Rajasthan is also culturally divided into regions: Shekhawati (Jhunjhunu, Sikar, Churu), Dhundhar (Jaipur, Dausa, Alwar), Braj (Bharatpur, Karauli, Dholpur), Hadoti (Kota, Bundi, Baran), Mewar (Udaipur, Chittorgarh, Bhilwara), and Marwar (Jodhpur, Barmer, Jaisalmer). Considering this cultural aspect was also critical."

The verdict was surgical. Following the Panwar committee's inputs, on 28 December 2024, the government announced that 9 of the 17 new districts created by the Gehlot government would be merged back into their original districts.

The nine districts were Jaipur Rural, Jodhpur Rural, Sanchore, Shahpura, Dudu, Kekri, Neem Ka Thana, Anupgarh, and Gangapur City.

With the latest decision, the state now has only 41 districts.

"Despite speculation about political motives, the committee's recommendations were grounded in practical considerations, and followed specific parameters," a senior official from the committee tells Swarajya.

The data-driven approach had produced what its advocates argued was a more rational answer to "how many is enough?"—but it would create its own set of winners and losers.

Success Stories: When Additional Districts Work

The districts that survived the Panwar committee's review offer examples of when administrative multiplication actually improves lives.

Khairthal-Tijara is one of eight new districts formed as part of Rajasthan's latest administrative restructuring. Other newly created districts include Balotra, Beawar, Didwana-Kuchaman, Kotputli-Behror, Deeg, Salumber, and Phalodi.

The district shares strong industrial linkages with both Delhi and Jaipur. It was formed by rearranging the parent district of Alwar in 2023 by the state government, then headed by the Congress with Ashok Gehlot as the chief minister. It has seven tehsils, seven municipal councils, and 152 gram panchayats. This region includes the Bhiwadi industrial belt, which is among the largest GST contributors to the state government.

Though this has been the only major upgrade since the district was formed almost two years ago, officials are hopeful about future developments. "As it is the district headquarters, this hospital will eventually be upgraded into a district hospital, with all specialised departments," the PMO said.

Another success story is Kotputli-Behror, which was created by restructuring Jaipur and Alwar. The officials here say that smaller districts will help bring better health, education, industries, and agricultural services to the people. It also helps to maintain law and order. Also, with better access, officials can understand local issues in detail and deliver government schemes faster to villages, towns, and cities.

"Jaipur is so big, and busy. Now for this region, the distance for all, cities and villages, from the district headquarters, is reduced. This increases communication between the common people and the administration," officials at the DM's office state.

From a revenue perspective, the resources and income that earlier went to the larger district can now be used completely for the development of this region. The Additional District Magistrate of Kotputli tells Swarajya that mining is a major source of income for the area. Along with this, transport and excise revenues will also be properly managed for the new district.

Earlier, this area was part of Jaipur, and only a small share of the Jaipur budget was spent here.

These examples suggest that district creation works best when regions have sufficient population, economic activity, and geographic coherence to sustain independent administration.

Casualties of Change and Rationalization

But the scientific approach created its own casualties—communities that had briefly tasted administrative independence only to have it snatched away.

The most poignant example is Neem Ka Thana. About 120 km from Jaipur, Neem Ka Thana was also created as a new district from Sikar and Jhunjhunu by the previous Congress government. The decision was later reversed by the BJP administration.

However, the region has seen protests against the BJP government's decision to dissolve its district status since December 2024.

"This feels like a betrayal of a long-standing demand. The demand for district dates back to 1952. After a 70-year struggle, Neem Ka Thana was declared a district in 2023, only to be merged back in December 2024," a retired IAS officer from the region tells Swarajya.

Since the announcement, daily rallies and demonstrations have taken place. Some residents have even gone on hunger strike, demanding the restoration of Neem Ka Thana as a district.

The pain is compounded by what residents see as arbitrary decision-making. "This region met all the criteria set by the Panwar Committee. People here have to travel 90 to 100 km to Sikar for any administrative work. In some villages, the distance is as much as 120 to 130 km," he adds.

A major concern raised is that the Panwar Committee visited most of the new districts but skipped Neem Ka Thana entirely. "We have a population of 12 lakh, which is higher than Deeg district. Its area is around 3,300 sq. km, while Deeg's is only 2,100 sq. km," Suresh Modi, MLA, Neem Ka Thana tells Swarajya.

"The district headquarters for Neem Ka Thana is in Sikar, which is 85 km away. In comparison, Deeg's previous district headquarters, Bharatpur, was only 32 km away," he adds.

The human cost of the reversal is visible in the dismantling of barely-established infrastructure. According to locals, during the 14 months it functioned as a district, several administrative offices were set up, and officers, including a district collector and SP, were appointed. Now, these departments are being slowly shut down. Officials have been transferred back to the state secretariat and to Bhiwadi.

The Smallest District Experiment: Dudu

Perhaps the most telling case study in the limits of district creation is Dudu, which became an emblem of how good intentions can collide with practical realities.

Jaipur was divided into four districts: Kotputli-Behror, Dudu, Jaipur City, and Jaipur Rural. Of this, Dudu transitioned directly from a panchayat to a district and became the smallest district in Rajasthan.

As per the Panwar committee's report, Dudu has a total area of 1,972 sq. km. In comparison, the average district size in Rajasthan is approximately 10,370 sq. km.

The committee also considered national and interstate averages. The national average district size stands at 4,212 sq. km, while in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, the figures are 5,940.12 sq. km and 5,604.45 sq. km, respectively.

In terms of population, Dudu has around 3.13 lakh residents. It was far below the threshold decided. For reference, Khairthal-Tijara's population is nearly 13 lakh.

"Dudu did not meet the requirements, and it was decided to merge it back with Jaipur. For administration, it was noted that managing such a small tehsil as a separate district would be inefficient," the official from the committee added.

A professor from Rajasthan University tells Swarajya, "Dudu is a very small area located right next to Jaipur. While there will be challenges for residents, making it a separate district is not a viable solution. It would have led to underutilisation of staff and resources."

"It is important to assess whether a proposed district is self-sufficient and capable of managing the revenue, development, and infrastructure. Districts that are small in size and located adjacent to large urban centres struggle to grow independently."

The committee recommended, instead, the establishment of offices for an Additional District Magistrate, Additional Superintendent of Police, and other key departments to improve local governance.

The Unresolved Question

Two years after this experiment began, Rajasthan is still grappling with the consequences of its administrative cartography. The current state reveals both the promise and the limitations of district creation as a solution to governance challenges.

As per locals, infrastructure continues to be a major issue in most new districts, with several office buildings incomplete or under-equipped. To support the development further, the state government, in its 2025-25 budget, allocated Rs 1,000 crore for the development of eight newly formed districts, however, further process is yet to begin.

Even the successful districts face ongoing challenges. For instance, Kotputli-Behror district was formed by merging two areas. "But there are disagreements emerging over the location of key offices like the district court. While Kotputli is the headquarters, people in Behror want facilities closer to them," an official adds.

However, there are still several logistical challenges which need attention. Many departments still operate from rented buildings or makeshift rooms. "Many departments do not yet have dedicated offices or full staff, and some still run from their old setups."

The persistent problems reflect a deeper tension in Indian governance: the desire to bring administration closer to people versus the practical constraints of resources and efficiency.

A retired journalist tells Swarajya, "The idea was to decentralise governance and increase development in our region, which would also help the state's economy. But the political tug-of-war between the two parties, especially around elections, has made our region a victim."

Critics of the entire exercise argue that both approaches—revolutionary expansion and scientific contraction—missed the point. However, critics state that the move of the Congress government was politically motivated, aimed at gaining electoral support rather than improving governance. The idea was to appease local sentiments.

Despite this bold administrative step, Congress failed to retain power in the Assembly elections of 2023.

The differences between the decisions of Congress and the newly formed BJP government led to the state district map being redrawn twice since 2023. While some await progress with the new administrative changes, many of the cancelled districts continue to raise concerns about the decision.

Thus, while the restructuring promises several benefits, many administrative challenges still remain. While some regions continue to demand new districts, the newly formed ones are still working through operational issues.

At 41 districts, Rajasthan continues its search for the optimal number. The question that began this journey—how many districts are enough?—remains as complex as ever.

For Phool Singh, traveling 25 km for dialysis instead of 70, the answer is clear: enough to make basic services accessible. For Neem Ka Thana's residents, mourning their lost district status after a 70-year struggle, 41 is still too few. For the state exchequer, even 41 districts strain resources and administrative capacity.

Perhaps the real lesson from Rajasthan's two-year experiment is that "enough" can't be determined by any single metric—whether it's political ambition, scientific parameters, or fiscal constraints. The optimal number of districts depends entirely on what you're optimizing for: accessibility, efficiency, political satisfaction, or administrative coherence.

What's certain is that the question won't go away. As long as Rajasthan remains India's largest state by area, with vast distances between administrative centers and the people they serve, the tension between centralization and decentralization will persist.

The map may be redrawn again, as future governments grapple with the same fundamental challenge that has consumed the state for two years: In a democracy, how close is close enough?