Technology

How Bharti Airtel May Have A Lead Role To Play In Global Delivery Of Internet From Space

Anand Parthasarthy

Dec 26, 2020, 05:30 AM | Updated Dec 26, 2020, 12:15 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Terrestrial Internet, as we know and use, is so yesterday. The most ubiquitous global data network, covering every inch of the earth, from pole to pole, will now be delivered from space through a garland of hundreds, possibly thousands, of small table-top-sized satellites.

And a savvy move, by a private entrepreneur, offers a historic chance for India to leapfrog into this new — and very imminent — era of Internet from space, even as she imprints the new technology with her brand.

On 18 December, UK-based communications company OneWeb announced a jumbo launch of 36 communications satellites, at one go, by a Soyuz launch vehicle in Russia. This brought the company’s tally of satellites in space to 110 — the first stage in the eventual launch of a 648-strong satellite fleet.

They would hover just 1,200 km above the earth (30 times closer than the geostationary satellites that provide global navigation services like GPS — and India’s NAVIC).

The promise is to provide a global Internet service covering the world in a manner that has not been possible before — leaving no surface unconnected — Arctic, Antarctic or equator, at data rates, almost, but not quite, matching terrestrial Internet.

As an aside, OneWeb’s announcement pointed at the two big co-owners of this enterprise: the British government and Bharti Global (part of Bharti Enterprises who run Airtel, India’s largest mobile service and the third-largest cellular operator in the world).

The two players each own approximately 45 per cent of OneWeb, having just weeks ago, pitched in half a billion US dollars each, to rescue the company from bankruptcy.

This infusion had ensured continuity of her plans — and propelled her simultaneously, to a lead position in the world-wide race to be first with a space Internet offering.

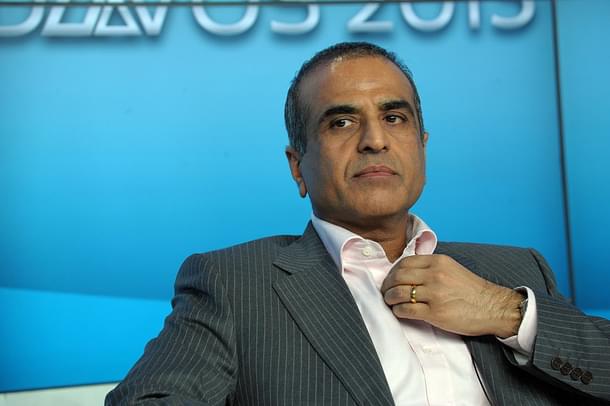

Sunil Bharti Mittal, Chairman of Bharti Enterprises, is now Executive Chairman of OneWeb, bringing to an Indian company, a unique oversight of a cutting edge, international project.

Consider this: The parent company is based in the UK, the satellites are manufactured in the US and lofted into orbit by a Russian space vehicle; with the Indian co-owner tasked with “acting as testing ground for all products, services and operations”.

The announcement of OneWeb’s second coming stressed the key role to be played by the Indian entity: “Bharti will contribute significant contract value to OneWeb through its presence across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where the terrain necessitates the use of satellite-based connectivity, providing a near-term anchor customer for large-scale global deployment of OneWeb’s services.”

Benefits for India

WebOne expects to start Internet services in 2021 across swathes of the northern hemisphere — including the north polar region which has never been illuminated till now. As more satellites join the network, India could be offered high-speed Internet around the middle of 2022, Mittal assures.

But some regulatory issues may have to be addressed. Unlike the co-investor UK, Bharti is a private player and would need the consent and cooperation of the Indian government, including agencies like ISRO, before Indian enterprises and lay customers can install user terminals.

In any case, satellite-based space Internet remains the costliest method of delivery compared to fibre cables and mobile wireless. It makes its case by promising broadband connectivity to vast interior regions left unconnected or under-served, as well as a reliable communication tool in disaster situations.

Other options

That last role has hitherto been played by satellite phones fuelled by relatively small number (8-10) of geostationary satellites run by companies like Iridium, Globalstar, Thuraya and Inmarsat.

These satellites hover 36,000 km above the earth unlike the low-orbit 1,200 km of OneWeb and use large receiving antennas on earth.

Inmarsat maintains an earth station at Ghaziabad in the national capital region and this helped it to tie up with BSNL as an Indian partner to offer its iSatPhone handsets and a Global Satellite Phone Service (GSPS) which includes voice calls and Internet access.

These services compare in cost to the tariffs for international calls made from hotels or from airlines which offer a cabin phone. The longer travel time for the voice or data means such traditional satellite phone services suffer a sometimes irritating “latency” or time lag between saying or sending something and its reaching the recipient.

OneWeb also faces competition from other enterprises who have also announced low-orbit satellite internet projects — Amazon’s Project Kuiper and the Elon Musk-led SpaceX’s Starlink — but have not yet put systems in place (See Swarajya, August 4 2020).

The Economic Times reports that the government-owned Telecom Consultants India Limited (TCIL) has partnered with a British provider, Methera, who will provide satellite-based broadband services in 2022-23.

It is not clear whose satellite network they will use.

OneWeb currently has a first mover advantage and the UK-Bharti kitty may buy it the ability to be first-to-market. But it remains to be seen if Internet from space can expand its role from a technology to illumine the world’s unconnected stretches to anything like the ubiquity of current Internet services.

And for the Indian government, this presents an opportunity that might possibly dovetail with its stated ambitions to play a leadership role in technology on a global stage.

It will have to decide if endorsing and supporting the global role of a private India-based player in futuristic technology, could be an unquantifiable but useful ‘message’ — or just the hard-nosed and techno-commercially savvy thing to do.

Anand Parthasarathy is managing director at Online India Tech Pvt Ltd and a veteran IT journalist who has written about the Indian technology landscape for more than 15 years for The Hindu.