World

The Great Indian Diaspora: Remittances, Costs, Populism And Future

Aryamsa

Jan 19, 2025, 02:07 PM | Updated Feb 01, 2025, 02:27 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Indian subcontinent has a long and storied history of diaspora communities, from the pioneers who carried Hindu culture to Southeast Asia more than a thousand years ago to the indentured servants of Trinidad who left their homeland in less favourable circumstances just a few centuries ago.

Cultural memory of the former still exists in festivals like the Bali-Jatra, which celebrate mariners from Kāliṅga who took perilous journeys to the Golden Lands of Suvarṇadvīpa: Bali, Java, Sumatra, and the Malay Archipelago. Indo-Trinidadians left their mark on the world with the haunting prose of Naipaul, the greatest Indian travel writer.

Today, the nature of emigration differs from the ninth or the nineteenth century, as does the diaspora's face. India also finds itself in an entirely different political and economic situation; it is no longer a varied collection of pre-modern feudal states or a colony of the British without sovereignty.

This article aims to get a brief historical overview of this everchanging Indian diaspora in the modern world, analyse the second-order effects of this diaspora, and look at the recent discussion on X (formerly Twitter) about high-skilled Indian immigrants to see what the future for this diaspora holds.

The 19th century saw the end of chattel slavery in the British Empire, with other countries like the United States (US), France, and Brazil following suit. However, the demand for cheap and free manual labour did not subside, so the system of indentured servitude was used to provide labourers to work the plantations in different colonies. India was the biggest labour market for the British, and more than 1.6 million Indians were sent by the British to work in plantations across the Caribbean, Fiji, South Africa and the Malay Archipelago.

This near-century-long emigration from India led to the creation of a sizeable number of Indian communities scattered across the globe, the first Indian diaspora in the modern world. The Indian emigrants came from all parts of India and were chiefly Hindus. Still, region-wide migration often differed, leading to mostly Tamils moving to Malaysia and mostly Bhojpuris from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to Trinidad and Guyana.

The Indian diaspora forms a sizeable part of many of these countries: 46 per cent in Mauritius, 40 per cent in Guyana, 38 per cent in Fiji, 35 per cent in Trinidad, and around 6-8 per cent in Malaysia and Singapore each. Indians have held political power in many of these countries. Chacha Ramgoolam was the first Prime Minister of Mauritius, and his son, Navin, is the present Prime Minister. The President of Singapore is a Jaffnese Tamil, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, and the first leader of independent Guyana was also an Indian, Cheddi Bharat Jagan.

There was a very small diaspora outside these countries, namely in the United States, the United Kingdom and the so-called ‘White Dominions’ of the British Empire, chiefly in Canada and Australia. South Africa was also a White-ruled dominion of the British Empire but had a sizeable Indian population (about 3-5 per cent) that had come over as indentured labourers and traders. Uganda was another country in Africa with a sizeable Indian population.

Gujarati traders facilitated the opening of money markets in Africa and acted as intermediaries between the English colonialists and the African natives while indentured labourers worked to build the railroads. British colonial policy had long encouraged the emigration of Hindus to other parts of the British Empire, especially in British Africa, to act as an intermediary class of administrators and officers between the Whites and the Blacks.

“On the whole, I think the admixture of yellow that the Negro requires should come from India. The mixture of the two races would give the Indian the physical development which he lacks, and he, in his turn, would transmit to his half Negro offspring the industry, ambition and aspiration towards a civilised life which the Negro so markedly lacks.”

Statements such as the one above by Henry Hamilton Johnson, one of the early British Commissioners responsible for the ‘Scramble of Africa,’ highlight the utility the Indians had in Africa for the British.

A policy of fairly liberal initial settlement in the non-White colonies was accompanied by restrictive laws and anti-Hindu racism in the rest of the Anglosphere. From the get-go, there were acceptable boundaries the Hindu migrant was supposed to follow. At this stage in the early 1900s, all migrants from India were called ‘Hindoo,’ despite the majority of Indians in North America being Punjabi Sikhs.

Indians could technically move anywhere in the British Empire due to being British citizens. Still, White-dominions like Canada and Australia had race-bound policies in place, which ensured migration from Hindus was very limited to none. Canada had the ‘continuous journey policy’ enacted in 1908 that barred migrants who came from a country or port of origin other than the country of their birth. The large distance between Canada and India meant that Indians were the only ethnicity barred from moving to Canada. The ‘White Australia’ policy that lasted till the mid-1980s similarly made it very difficult for Indians to move to Australia despite being British and later, Commonwealth Citizens.

Before 1940, less than 6,000 Indians lived in the joint-contiguous United States and Canada combined. They were such a micro-minority that they appeared as blips on official census data. The figures for Australia and New Zealand were similar. Great Britain had a lot more Indians, at a little over 7,000, in 1931; almost all were men and all from well-to-do families who had sent their male sons to study and live in England as Imperial subjects.

Gandhi, Jinnah, and Nehru were examples of this class of migrants: posh, English-educated, Barrister, politically active with cultural tastes similar to the English bourgeoisie rather than their countrymen.

While citizenship was not an issue in the domains of the British colonies, it was in countries like the United States, which explicitly barred Indians and other Asians from becoming naturalised American citizens.

However, children born to such aliens were still given citizenship based on jus soli. There were so few Hindus in the United States before WWII that their legal racial status was still unclear, and many Hindus (including Sikhs) had naturalised successfully as ‘free white men’ before the Supreme Court decided to declare Hindus as non-Whites in the United States vs Bhagat Singh Thind 251 US 204 (1923).

A lot of Hindus, such as Sakaharam Ganesh Pandit, were stripped of their American citizenship, a violation that was fought in court till the decision was made that existing Hindus with American citizenship would not be stripped of it. Still, the doors for new migrants wanting to naturalise will remain closed. Not all Indians were treated the same way.

Parsis such as Bhicaji Balsara were successful in having the courts view them as ‘free white people’ due to being of Persian extraction and were hence given citizenship, though this did not go unchallenged either, for the courts argued that Middle Easterners might be White but did not come from ethnicities that represented the

founding stock of the European races that had built America. The few Indians who existed in America during this time were subject to immense racial and societal discrimination, being seen as cultural, racial and religious aliens who did not even share the tenets of the Christian religion in common, unlike Arab, Armenian Christians or the American Negro.

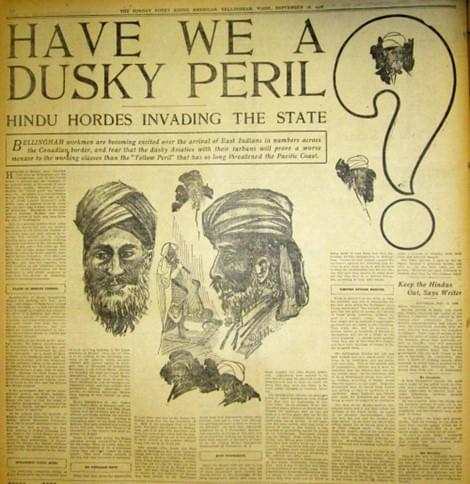

In 1907, the lumber and fishing town of Bellingham, Washington, saw anti-Indian riots mostly targeting the Punjabi Sikh labourers who were seen as religious and racial aliens stealing the jobs of working-class White men in the town. On the 4 September, mobs of rural and working-class White men gathered to beat the ‘Hindoos’ and drive them out of the city to take back their lost jobs. The subsequent violence against the Indian labourers who worked in the lumber mills led to them fleeing Washington after realising no protection from the city authorities was going to come. The local newspapers justified the mob violence by pointing out how ‘Hindoos’ must not be allowed to take jobs from the local White people.

The Seattle Morning Times said:

“It is not a question of race, but of wages; not a question of men, but modes of life; not a matter of nations, but of habits of life… When men who require meat to eat and real beds to sleep in are ousted from their employment to make room for vegetarians who can find the bliss of sleep in some filthy corner, it is rather difficult to say at what limit indignation ceases to be righteous.”

While other papers, such as The Reveille, declared:

“While any good citizen must be opposed to the means employed, the result of the crusade against the Hindus cannot but cause a general and intense satisfaction, and the departure of the Hindus will leave no regrets.”

Laws prohibiting Indians from naturalising stayed in place till the mid-1940s, when the passage of the Luce-Celler Act in 1946 opened the doors for Indians to migrate to America and naturalise as citizens in a limited quota of 100 people each year, per the principles of the National Origins Formula that created racial migration quotas that gave the most preference to North-West-Europeans and the least preference to ‘Oriental’ Asiatics in the yearly migration quotas. As late as 1952, more than 94 per cent of immigrant quotas were given out to Europeans, and this would remain the case till the Civil Rights reforms of the 1960s and the passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

The post-war world is where the origins of most of the Indian diaspora in the Anglosphere can be traced back to with hundreds of thousands of Indians leaving for the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia from the 1950s to the 1990s. A liberalisation in migration laws and an end to outwardly racist attitudes led to an influx of economic migrants from older colonies and the rest of the Third World.

In Great Britain, newly minted Commonwealth citizens could freely migrate to the UK under the British Nationality Act of 1948. The British-Indian population more than doubled from 1951 to 1961 (30,000 to 80,000) and more than quintupled from 1961 to 1971 (about 400,000). Similar figures existed for other subcontinentals, such as Pakistanis, with many migrants coming from Punjab.

After WWII, Punjabi soldiers who had fought and lived in England and the rest of Europe were more proactive in moving abroad due to greater awareness and sending the message back home about opportunities for work in English factories in the Midlands. Then there were traders and peasants from Gujarat who also had a vibrant diaspora of East African Indians that had moved to England after being expelled from places like Uganda in the 1970s. This word of mouth and increased social mobility led to many British Indian migrants coming from Gujarat and Punjab.

While the Anglosphere was becoming more accepting and tolerant of Indians mostly because of how few of them existed locally, the erstwhile colonies of British East Africa and Burma were conducting mass expulsions of their mercantile Indian elite.

Increased negative attention as intermediary traders of the British Empire also drew ire from the locals, which led to increased anti-Indian and anti-Hindu sentiment in post-independence African countries such as Uganda. Populist dictators such as Idi Amin called for a public expulsion of Indians in Uganda, citing their clannish non-integration, refusal to let their women marry Ugandan men and crony capitalism as the reasons for stripping more than 100,000 Indians of their Ugandan citizenship.

The irony of this is that the richest man in Uganda, Sudhir Ruparelia, is still an Indian and Indians contribute more than 65 per cent to the total tax revenue of the impoverished African state despite being less than one per cent of the population.

Burma was another of the post-war British Raj colonies that saw heightened anti-India racism and calls for expulsion of the Chettiar Tamil mercantile elite that dominated trade in Burma, with the capital Rangoon being more than 50 per cent Indian before the war. In the mid-1960s, the Burmese socialist dictator, Ne Win, conducted a nationalisation of Indian-owned businesses and state-directed seizure of land and wealth, along with calling for an expulsion of all Burmese Indians.

During the same period, Indian migration to the United States started picking up a rapid pace after the 1960s, with nearly 50,000 migrants coming into the country every decade till the 1990s. Australia ended the ‘White Australia’ policy in 1975, and Canada also liberalised its immigration laws, introducing a points-based system in 1976 and abolishing racial quotas.

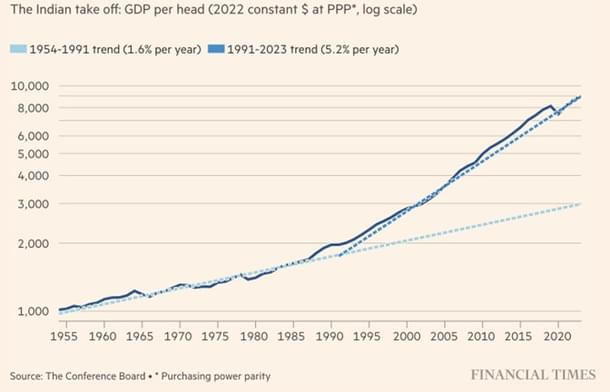

This led to the influx of many middle-class working professionals from India into the Anglosphere, forced to migrate due to a completely stagnant and socialist Nehruvian economy that grew at an abysmal 3 per cent compounded annually from the 1950s to the 1980s, with little to no market liberalisation or increased productivity that led to no growth in per-capita incomes.

GDP Per Head in 2022 Constant US$ only increased by 1.6 per cent per year from 1954 to 1991; for nearly 40 years, there was no growth in living standards in India. While the rest of the Asian tigers were reaching Upper-Middle income levels, India was still stuck in the 1950s, and its large English-speaking working professional population found good opportunities in a liberal and anti-populist Anglosphere. The 1990s saw the rise of the Internet Age and the dot-com boom in the United States, leading to even increased numbers of Indian immigrants to the US, almost 100,000 people per decade in the 90s and 2000s.

This had all been facilitated by the Immigration Act of 1990, which more than doubled the annual immigrant cap to 700,000 and created the H1Bnonimmigrant speciality visa, as well as five kinds of EB visa, expanding it to religious workers and others, and making the diversity green card lottery for underrepresented nations, further increasing immigration. By 2010, there were 2.8 million Indian-Americans, accounting for around 1 per cent of the US population, doubling every decade from 1990 to 2010. These 20 years saw a flood of high-skilled migrants into the US economy, slowing down only after the 2008 GFC and the worst recession in American history since the Great Depression.

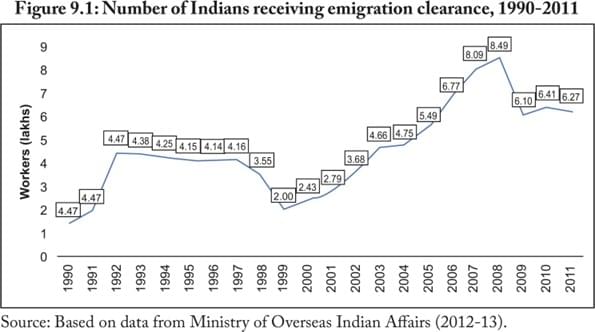

While the United States or the Anglosphere remained the favoured destination of high-skilled Indian migrants, the Gulf Countries (Saudi, Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, etc.) were where most low-skilled Indian emigrants moved from the 1970s to the 2010s. These emigrants filled the role of semi-skilled wage labourers, drivers, cooks, maids, and sweepers, helping to build the cash-rich cities of the Gulf during their oil boom.

Nearly 90 per cent of the emigrants in the 1970s and 1980s were semi-skilled workers, though the percentage of high-skilled workers such as engineers, architects and doctors has risen in recent years.

These semi-skilled emigrants need an emigration clearance from the Indian government before being able to go and work abroad, a system designed to protect their labour rights in their work country and not let their recruiting agents exploit them. These Indian migrants to the Gulf differ from those to the Anglosphere or Europe because most of the GCC countries do not let them gain a pathway to citizenship or equal rights.

Rather, they use them as temporary labour and then send them back. At the same time, the Anglosphere gives clear pathways to citizenship and voting rights. The Sharia as law in the Gulf monarchies further acts as a deterrence for migrants, in contrast to the secular liberal democracies of the Anglosphere.

This brings us to the second half of this article, namely the economic impact of this large Indian diaspora on India. Foreign Remittances from the diaspora to family back home have largely been considered the greatest benefit of these 40 million large diasporas. India is the largest receiver of remittance money, with US$125 billion received in 2023, up from US$70 billion in 2017. Annual remittances to India have remained a constant 3 per cent of GDP from the 1990s. India accounts for about 15 per cent of all global remittances. However, these remittances are rarely scrutinised for negative second-order effects, of which there are a few.

Some Indian states, such as Kerala, have created a domestic economy based entirely on remittances from the Gulf, with almost 30 per cent of the state’s GDP coming from the same, leading to a complete lack of industrial growth and record-high youth unemployment, the third highest in the country, due to a lack of job opportunities.

One of the underlying reasons for the rise in remittances is the explosion of Indian students studying abroad from 2016 onwards. Over 1.8 million Indian students are now studying abroad, with Canada topping the list at 427,000 students, followed by the United States at 337,630, the UK at 185,000, and Australia at 122,202, among others. The total number of Indian students abroad rose from 907,404 in 2022 to 1,318,955 in 2023 and then to around 1,800,000 in 2024 — a 98 per cent increase in just two years.

This explosion of Indian students studying abroad happened in the last 10 years and comes with enormous costs for the Indian economy while bringing immediate cash infusions into the countries they go to, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars for their degrees, and then adding young skilled labour to counter falling birth rates and a stagnant economy in countries like Canada, the UK, Australia and the US. Indian families will spend US $75-$85 billion in 2025 on their children’s foreign education and foreign living expenses, up from a mere US $37 billion in 2019, more than a 100 per cent increase in just 6 years.

This is money sent out of India by the highest-paid working professionals in the country who have either liquidated familial assets, used up their savings or drawn out debt worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. These costs are somewhat new because migrants today are largely young high-school and graduate students going abroad to study in diploma mills to find a path to permanent residency in countries like Canada, encouraging Canadian diplomas to get Permanent Residency.

These migrants differ from middle-aged working professionals moving lock, stock and barrel with their families on professional work visas like the H1b or L1 visa because of the enormous costs incurred in educating and housing students while they complete their degrees. The fees are incurred by their families back home, translating to rupees leaving India to give dollars to foreign universities and their local communities. Once the students graduate, they live and work in the countries they have migrated to. Hence, this is a worse form of brain drain because it directly cuts into the remittance money by costs incurred on foreign education, all while leading to educated young students leaving the country.

India has an abundance of cheap manual labour, and it doesn’t take long to realise why it’s better to earn foreign currency from exporting this manual labour abroad on temporary work contracts rather than spending nearly US $85 billion to send English-educated engineers, doctors, lawyers, and accountants abroad. A good example of this is Israel switching over to using Indian construction workers from Palestinians after the 7 October attacks by Hamas that led to the death of 1,150 Israelis. There are more than 30,000 Indian construction workers in Israel now, and they are paid more than RS 200,000 a month (about US $ 2500), almost ten times the median wage for construction workers in India. Similar programs are being looked at by friendly countries facing low fertility rates and labour shortages, such as Taiwan.

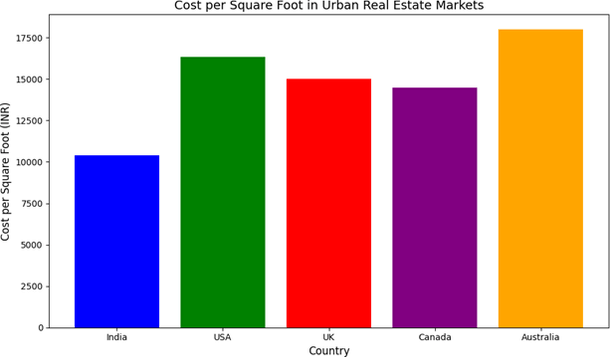

The other less talked about economic issue a large diaspora brings is its effect on overheating the already inflated domestic real-estate market. India has one of the priciest urban real estate markets in the world; the average cost per square foot in Indian urban markets is RS 10,000-12,000 (US$115-140) while the housing cost per square foot in the United States is about RS 16,000 (US$200). The average urban Indian earns an income that is twenty times lower than the average American but has to deal with an urban market that is nearly evenly priced. It’s difficult to use the rural Tier-2 and Tier-3 city housing markets in India to compare since most well-paying jobs exist only in Tier-1 cities that are already overcrowded.

There are a few reasons for this housing crisis: corruption in Indian real estate, stringent FSI norms, scarcity of big urban centres, and NRIs buying up the already scarce housing as an investment for the future. Between April and September of 2023, more than 20 per cent of homes sold by DLF were bought by Non-Resident-Indians who haven’t lived in India for years.

The urban real estate market is also affected by low Floor-Space-Index (FSI) ratios, which limit the built-up area on the plots. Mumbai has an FSI of 2.5, while New York City has an FSI of 15 — this means that a 100 sq m plot can have 6 times the built-up area that the same plot in Mumbai can. This prevents vertical constructions and lowers urban population density, but also increases the cost of housing. Real estate developers can purchase FSI limits from state or municipal governments at extra rates, another source of corruption and kickbacks to the city from developers.

Poor infrastructure and urban planning also prevent the increasing FSI limits at the Shanghai or New York levels. Vertical constructions depend greatly on the availability of electricity, power, water, and sewage disposal. So, the diaspora is not the only reason for an inflated urban real-estate market in India, but the money they pump into the market certainly helps overheat it.

So far, the purpose of this article has not been to portray the diaspora in an entirely negative light but to examine some of its less-discussed second-order economic effects.

The remaining part of this article is concerned with understanding the conditions that led to the creation of the modern Indian diaspora and the impact of xenophobic attitudes on the future of this globalised diaspora.

We have seen that the attitudes of the locals surrounding Indian migrants influenced laws related to immigration a lot, with many countries seeing xenophobia spill over into racial riots targeting working-class Indians or the Indian elite, blaming them for the lack of opportunities or a slumbering economy. It was only the historically liberal post-WWII attitudes of the Western world that created the liberal climate tolerant of immigrants, and if that climate were to change, what would the future of this diaspora be?

Anti-Indian sentiment has been on the rise in recent years. In the US, FBI data shows hate crime incidents climbed to 11,G34 in 2022, up from 10,840 in 2021 — a 7 per cent increase. Of these, nearly 60 per cent were motivated by race or ethnicity, and a growing subset was linked to Indian or subcontinental identity.

One study of extremist online spaces also recorded a doubling of anti-Indian slurs over the past year, from about 23,000 to more than 46,000, with threats of violence similarly rising. In Canada, hate crimes against Indians and other subcontinentals went up by 143 per cent from 2019 to 2022, with a quarter of migrants saying they had faced racially charged discrimination. 60 per cent of Canadians in 2024 felt immigration had gone out of control and needed to be checked, a number that doubled in two years from under 30 per cent in 2022.

These sentiments partially stem from the presence of millions of foreign students and working professionals in the Western world, record-high rates of illegal immigration in countries like the United States, the rise of a technocratic-political elite of non-Western origin, record-high rates of consumer inflation, low growth after the COVID-19 pandemic, and an increasingly unaffordable housing market. In the worst-hit countries like Canada, the new Indian migrants add to the labour supply but rarely take up jobs in the construction industry (less than 3 per cent work in construction), adding new homeowners but not filling the gap in producing more houses.

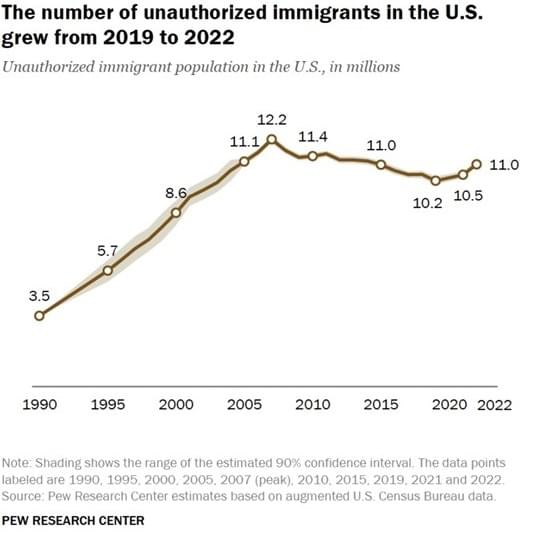

In the United States, 2021-2024 saw record inflationary rates, peaking at 8 per cent annually in 2022 and staying above 4 per cent for nearly three years straight. This was coupled with an almost 40 per cent increase in housing prices between 2022 and 2024 and record-high rates of illegal immigration, 2 million every year from 2021-2023 in the Biden administration. These conditions of slowing economic growth and worsening living standards have led to the rise of populists across the West: Donald Trump, Viktor Orban, Alice Weidel, Pierre Poilievre, and Javier Milei.

The weakening of border security along the Southern border of the United States also led to a large increase in illegal immigration from India to the United States, the infamous ‘dunki’ route. According to Pew Research, Indians are the third largest group of illegal immigrants in the United States as of 2022, with 725,000 living without papers in the country.

These migrants from India are not from the poorest strata of society. They are usually peasant landlord farmers without many sources of income except their land and no English education. They cannot obtain a student visa and pay exorbitant amounts of money (US$100,000) to agencies specialising in this. These migrants are usually from Punjab, Haryana, and Gujarat. In January 2022, the tragic death of a family of four from Gujarat who froze to death trying to cross the border from Canada into the US highlights the insanity of this craze to go abroad at any cost in large parts of the country.

Trump’s recent election win was widely seen as a voter mandate to intensify immigration enforcement and reshape the system. He campaigned heavily on promises to secure the border and prioritise the removal of undocumented residents. Yet his public statements since the election reveal competing impulses on legal immigration — from pushing to end birthright citizenship guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to championing the idea of “stapling” green cards to college diplomas for foreign graduates.

Throughout his campaign, Trump promised to fix perceived abuses in the H-1B system, suggesting he would tighten eligibility for foreign hires. He also described himself as a “believer in H-1B” who wants highly skilled workers to bolster the US economy. His stances on legal immigration have been fuzzy, to say the least, with many accusing him of changing his mind on the issue due to close association with Silicon Valley tech elites like Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, who ostensibly support the H1B visa program and high-skilled immigration wholeheartedly.

In 2016, he promised to crack down on corporate abuse of the H1B visa program, saying on record:

"The H-1B program is neither high-skilled nor immigration: these are temporary foreign workers, imported from abroad for the explicit purpose of substituting for American workers at lower pay. I remain totally committed to eliminating rampant, widespread H-1B abuse and ending outrageous practices such as those that occurred at Disney in Florida when Americans were forced to train their foreign replacements. I will end forever the use of the H-1B as a cheap labour program and institute an absolute requirement to hire American workers first for every visa and immigration program. No exceptions."

Trump even signed the RAISE Act into law, which increased scrutiny on H1B applications and Green Cards; H1B rejection rates rose to 24 per cent in 2018 under Trump, up from 5-8 per cent under Obama and 3-4 per cent under Biden.

However, in the lead-up to the 2024 election, Trump was on record saying he would “staple green cards” to the diploma of college graduates, while his ‘border czar’ Tom Homan, talked about mass deportations of a million illegal immigrants, including joint deportations of families with or without their children, who may be American citizens by birth.

These contradictory positions of the Trump team highlight the tension that MAGA faces on the question of legal immigrants, having moved well past normalising the rhetoric of deporting illegal immigrants. The 2024 mandate rejects increased immigration, but to what extent? This tension has expanded further by adding people like Elon Musk, Vivek Ramaswamy, Robert Kennedy Jr and Tulsi Gabbard into the core ‘Trump Team.’

The latter two were democrats till yesterday and are reluctant members of this big-tent coalition mostly for their specific reasons: Tulsi Gabbard is one of the most anti-war democrats, and RFK Jr. is aligned with the Trump camp on vaccine denialism and was named the presumptive nominee for Health Secretary, giving him control over domestic policy on food control and safety standards among other things. Vivek Ramaswamy was a newcomer Pharma entrepreneur who ran as the Republican presidential nominee and dropped out after a moderately successful campaign given the odds, picking a spot in the Trump team.

Vivek is openly Hindu and has faced criticism for it from his base, with one attendee at a Penn State rally accusing him of being intentionally deceptive of his religion and drawing false parallels with Jesus Christ, accusing Hinduism of being a ‘wicked and false Pagan religion’. Despite this, Vivek was polling at nearly 12 per cent at his peak in August 2023, falling to less than 5 per cent before dropping out of the race in January last year.

However, the biggest new addition to the core Trump camp is Elon Musk, the richest man in the world and founder of some of the biggest American giants in EV manufacturing and space exploration: Tesla and SpaceX.

Musk has had a documented shift to the hard-right of the political aisle over the last three years; he purchased Twitter for US$45 billion in October 2022, promptly down-sized staff, and cut censorship from the site, citing his commitment to free speech. Musk has also cited familial reasons, such as one of his biological sons becoming transgender, as his reason for fighting the ‘woke mind virus.’

A lot of political discourse in the modern West revolves around rallying up a populist base around the ‘culture war’ and the negative socioeconomic effects of immigrants, usually Muslim, African or Hispanic. This is not rhetoric limited to fringe image boards such as 4chan anymore, but part of mainstream political discourse adopted by all conservative/nationalist parties in Europe and America.

This rhetoric also translates into actual political victories, with once-marginalised far-right political parties such as Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) winning almost 100 seats in the German parliament in 2017 and currently polling at 21 per cent for the 2025 Federal elections, the second most popular party after the centrist Christian Democratic Union (CDU/CSU). In Holland, the anti-Muslim populist party of Geert Wilders, Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV), became the largest party after the 2023 elections, winning nearly 25 per cent of the popular vote and forming a coalition government.

The populist rhetoric of these European parties has usually focused on the crime committed by Muslim migrants in Europe, which again leaves Hindus from India in a bit of a fuzzy spot. Hindus are foreign to Europe, but they are productive migrants who commit almost no crime; in the United Kingdom, Hindus are 0.4 per cent of the British prison population while being 1.7 per cent of the country’s population.

A similar situation exists in the United States, where Indian Americans (more than 75 per cent of Hindu origin) are the richest ethnicity, with a median household income of US$145,000, surpassing all other ethnicities. The Asian population, 7 per cent of the United States, had just a 1.3 per cent share in total arrests made in 2019. Since this population is mostly made up of East Asians, the number of Indians arrested is likely below 1 per cent of all arrests made.

This again brings us back to our point: the populist right in the West has so far reserved its anti-immigrant ire for ethnicities and groups other than Indians and East Asians for reasons such as the ones listed above. However, this has started changing as Indians become an increasingly common face in the Western world and hold immense political and economic power positions.

The Vice President of the United States is half-Indian and was raised by her Indian mother. The first non-White Prime Minister of the United Kingdom was an Indian Hindu, Rishi Sunak. One of the forerunners for the Republican nominee for 2024 was an Indian Hindu, Vivek Ramaswamy. In addition, we see many Indians as chief executives of some of the biggest American companies: Satya Nadella, Sundar Pichai, and Arvind Krishnan, respectively, run Microsoft, Google, and IBM.

East Asians were seen as having a ‘bamboo ceiling’ that prevented them from rising to the top of the corporate and political hierarchy in the Western world; this ‘bamboo ceiling’ does not exist for Hindus in the Western world, which some research shows is likely because Indians are more assertive and opinionated, values which leaders are supposed to have in the Western world. However, being more visible in positions of power, politics and wealth as a visible minority group is also the easiest way to have a target on one’s back: this has been the case throughout history and was one of the main reasons for anti-Indian populist sentiment in Eastern Africa and Burma.

Add to this the fact that Indians are largely Hindu, a faith far removed from the rest of the Abrahamic religions, non-White, do not adopt Christian names usually, and statistically are not likely to intermarry with the locals. This makes the road to assimilation much more difficult for Hindus than it did for other minority elite groups with a lot of political power and wealth, such as Ashkenazi Jews.

Bringing this back to the immigration debate, we saw how Trump has had contradictory stances on legal immigration through the years but has generally been pro-legal immigration in the recent election campaign. One of the reasons for this is likely due to the influence played by Elon Musk, who played the role of a moderating voice on the issue. Musk gave almost US$300 million to the Trump campaign in 2024, becoming the largest mega-donor.

Musk also made his stance on immigration clear in the recent spat on X (formerly Twitter) about the H1B visa. We discussed the history of the H1B visa program before and the 85,000 non-immigrant dual intent (permissible to pursue a green card) visas it issues every year. Indians makeup 80 per cent of the recipients of these H1B visas and, hence, will naturally be the prime target of nativist and populist sentiments that consider high-skilled legal immigration to be just as harmful as low-skilled illegal immigration or immigration of violent and non-productive minority groups.

The spat began on X during the last week of December after the appointment of an Indian-American Venture Capitalist, Sriram Krishnan, as an advisor to the Trump White House on AI policy. Krishnan’s comments on removing the country-specific cap for Green Cards and speeding up the process for high-skilled legal immigrants to move to America caught flak from the populist and America First base of the online right wing. Musk fought with online factions of the populist right vehemently opposed to Indian immigration and all forms of high-skilled immigration.

Musk, himself an immigrant and owner of multiple companies that employ high-skilled Indian immigrants and sponsor their H1B visas, drew a clear and firm line on the issue, saying he would ‘go to war’ on this.

Trump immediately supported Musk on the issue despite criticising the H1B program in his first term and signing a policy into law that made it more difficult to get an H1B visa or a Green Card. Interestingly enough, Sriram Krishnan was a partner at Andreessen Horowitz (a1Gz), and Marc Andreessen and Horowitz gave almost US$10 million to the Trump campaign in 2024.

The Vice President-elect, JD Vance, decided not to comment on this controversy directly but retweeted and quoted people on the opposing side of this debate. After more than a week of discussion on this issue on X, Musk more or less pivoted to posting and talking exclusively about the Pakistani grooming gangs in England and demanding the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom conduct an inquiry into the Rotherham grooming gangs and the role played by British authorities in covering this scandal up.

This erratic posting by figures like Musk juxtaposes the tension that will eventually come up in any populist movement: will there be a line between good and bad immigrants, as there was before, or will this modern strain of Western populism turn against all forms of immigration? This is not to say that there is no credibility to such arguments; we have already seen how Indians, Hindus specifically, are the least likely migrants to be involved in violent crime and create a lot of wealth for the countries they go to.

However, nativist sentiments are not just based on econometric and crime data; they are based on emotions and feelings of tribalist belonging. Such modes of thinking died out in the West after the Second World War, and the economic prosperity provided by capitalism made people forget entirely about such concerns.

A combination of many factors: economic decline, unchecked migration, refugee crisis, violent crime and loss of jobs has led to the rise of such sentiment across the Western world, and as of now, we do not know where it will end. It would be foolish to assume that the racially charged riots and expulsions of Indians that we saw that happened less than a century ago cannot occur again; things like these can never be taken for granted because they depend on multivariate factors that keep changing with time.

This article aimed to gain a historical overview of the Indian diaspora, look at the challenges faced by the earliest Indian migrants, and scrutinise some of the non-positive second-order effects of such a diaspora on India.

The negative effects are rarely discussed in detail beyond generic comments on brain drain and dual loyalties, so we wanted to look at the domestic costs. We also wanted to use a realistic lens to analyse the rise of populism in the Western world and make it clear to the reader that it was the recoiling back of nativist sentiments which led to the Western world accepting migrants. It was the culmination of nativist sentiment that put a target on the back of wealthy Indian communities in Uganda and Burma and led to their eventual expulsions.

Liberal Western democracy cannot be taken for granted as many assume, for it will shrink back as populism rises in the West; it is only the extent to which this pushback happens that we are not sure of.