World

To Know What Is Happening In Islam Today, Go Back To 1979

Syed Ata Hasnain

Dec 15, 2015, 07:30 PM | Updated Feb 24, 2016, 04:21 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In today’s busy globalized world people have little time to read history, even the recent one. Their deductions about current happenings are drawn from day to day events and they remain content to feel well informed with that. If anyone really wishes to enter into debate on as serious a subject as Radical Islam for instance, he would be found wanting and perhaps the perceptions would all be flawed.

1979 could be considered a landmark year of the second half of the twentieth century; perhaps a shade more important than 1989 when the Berlin Wall fell and the end of the Cold War really commenced. Much of what we are witnessing in the turbulent zones – Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and Pakistan, owes its origins to the events of that year. In fact, the confrontation being witnessed between Islam (read Radical Islam and not entire Islam) and the rest of the world has its foundations in 1979 when three major events took place.

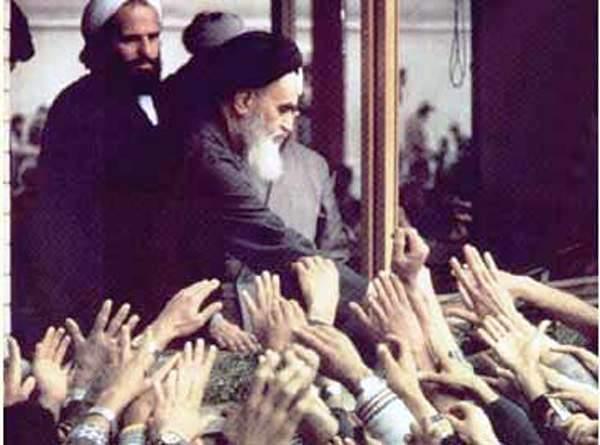

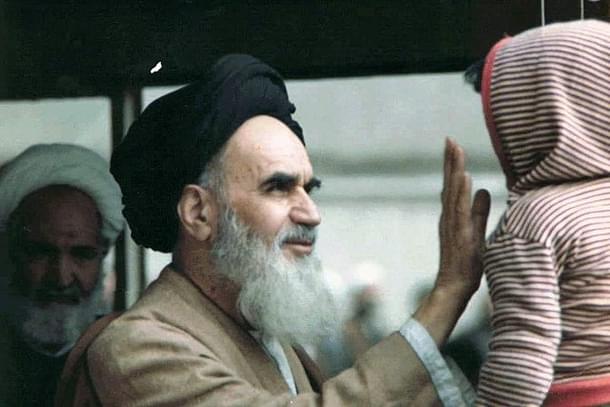

- First, a well-known one; the Iranian Revolution, leading to the overthrow and exit of the Shah of Iran; the taking over of power by Ayatollah Khomeini; and the US embassy hostage crisis in Tehran which involved holding hostage 52 diplomats and other US officials from 04 Nov 1979 to 20 Jan 1981 by revolutionary students with allegiance to Khomeini.

- The second major event of 1979 was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan commencing Dec 1979, leading to a prolonged nine year long war between the then Soviet Union, and Islamic proxies such as Pakistan’s ISI and transnational ‘mujahideen’ set up by the US.

- The third event was a relatively lesser known and remembered event of Islamic history; Juhayman al-Otaybi a member of the Ikhwan (soldiers of Saudi Wahhabism) and his followers took over the Al-Masjid al-Haram in Mecca’s Kaba as a mark of protest against the supposedly lax Islamic practices of the Royal House of Saud. The event took place on 20 November ’79 and the violent standoff, with taking of pilgrims as hostages, lasted almost 14 days. French Special Forces on invitation finally entered the area of the Holy Mosque to put an end to the resistance.

How these events, which took place within a span of less than 30 days, change the face of the world is one of the most interesting studies in contemporary history and worth an analysis for the readers. This short piece can only spark interest for greater study because it cannot link all subsequent events. The attempt will be to show just how these events triggered a chain of separate processes and trends which have all come to a head today.

Iran’s Revolution

The well known facts are important; the Shah, an autocrat with US support, was overthrown by a combination of youth, the clergy and a new found zeal in Islam to cleanse itself of Western influence. That the initiator came from Shia Iran and not from Saudi Arabia, the center of Wahhabi Islam, perhaps surprised the House of Saud. The sudden rise of militant Shiaism, as personified by Iran’s revolution, worried the Sauds who were always in the game of carefully cultivating their brand of extremist Islam. It was time to get pro-active about overcoming the Shia challenge and extending the Wahhabi reach. The opportunities came sooner than they could have anticipated but before discussing that it is pertinent to have a look at the other big ticket event – the Ikhwan action at the Kaaba.

Seizure of the Grand Mosque

The Islamic world was shocked when hostages were taken and militants, civilians and security forces killed in the seizure of the holiest site of Islam. The siege lasted two weeks, and the mosque was finally cleared by the French Special Forces who were invited by the Sauds. The House of Saud was accused of desecrating the Kaaba due to permission given for French forces to enter. The Sauds perceived the need for a stricter brand of Wahhabi Islam to offset this criticism and prove that they were equally energetic about the spread of their brand and maintain the equilibrium of their relationship with the powerful Saudi clergy. The opportunity to prove this came with a series of events commencing with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan

An earlier coup d’etat in Kabul had brought a pro Soviet regime to power in the underbelly of the Soviet Union. It was resisted through a rebellion in the countryside bringing the Soviet 40th Army into an invasion to further establish a pro-Soviet socialist regime under Babrak Kemal. Almost 5 million refugees fled Afghanistan to Pakistan and Iran as the violence increased. The West, led by the US, as also the countries of the Persian Gulf and some nations of the OIC financially sponsored and encouraged Afghan resistance supported by trans-national fighters from all over the mainly Sunni Islamic world.

For the Sauds this was a god-sent opportunity to project their pan Islamism and spread Wahhabi ideology. The hundreds of refugee camps set up on the Pakistan side of the Afghan-Pak border with the help of Saudi and US money became the centers of sponsorship of Wahhabi seminaries. It was a matter of convenience for the House of Saud and the powerful Saudi Wahhabi clergy between whom a tenuous balance of power has always remained. The clergy was content with the spread of its brand of Islam into Pakistan and Afghanistan where it was simpler to impose radicalism given the levels of poverty, low education indices, traditional gender issues and feudalism, all underscored by propensity for violence.

Strategically Saudi Arabia, as a nation, could not have expected anything better; a Wahhabi movement to establish roots deep in the territory on the flank of its traditional foe Iran whose brand of militant Shiaism had to be countered. The string of pearls around Iran would be further attempted after 1991 by spreading Wahhabi Islam into Central Asian Republics (CARs) after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

We can’t forget that it was the Soviet-Afghan war which gave opportunities to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (the father of ISIS), Osama bin Laden and Ayman al Zawahiri to emerge, showcase their leadership and be radicalized by the Islamic fervor on display. It was the passion sponsored from Saudi Arabia which was responsible for this.

The glue which helped Spread Wahhabiyat

On the sidelines of this emerging drama was a set of devious eyes which was watching and wondering at the luck which was coming its way. This was Pakistan where it’s latest military ruler, General Zia ul Haq, was keenly observing and ticking off the opportunities. These opportunities would help his strategic ambitions, chief among which was retribution against India for having destroyed Pakistan’s integrity by helping in the creation of Bangladesh. He had come to power riding a coup d’etat in 1977 and by 1979 had executed his civilian predecessor Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

He knew that the intended retribution against India could not be on the conventional battlefield; Pakistan had tried once too often and failed. There were only two ways by which he could achieve his aim. First, he had to acquire a nuclear capability to enhance deterrence, which needed money. Second he had to launch a war by a thousand cuts against India, a slow war to bleed India’s army; a proxy war fought inside India to exploit its fault lines.

His strategy could work provided Pakistan was close to the House of Saud and strategically linked to the state of Saudi Arabia. The finances, ideology and most importantly political support in the Islamic world would all come from that direction. Zia considered Pakistan the natural leader of the Islamic world but perceived that its shortcomings lay in lack of financial muscle. That could be compensated by the power arising out of being the only Islamic nation with nuclear weapons.

Zia provided the House of Saud an elite unit of his army for personal security; it built to a brigade by 1989. He also opened access to the refugee camps, helped set up seminaries, co-opted his intelligence agency—the ISI—to coordinate and eventually lead the trans-national mercenaries to counter the Soviet 40th Army in Afghanistan. The glue which provided the recipe for success on which rode the ‘Mujahideen’ was the extreme form of Radical Islam being spun out from the seminaries. It is in these tented colonies that the Taliban was born which struggled through the early Nineties to finally take over Afghanistan in 1996 with the help of the ISI.

Through 1979 to 1988, Zia most adroitly played his game acting as the surrogate of the US and Saudi Arabia in the game to defeat the Soviet Union. He died in Aug 1988 just before the withdrawal of the Soviets was imminent. Under him the radical brand of Islam was nurtured and used as a strategic weapon to bring the mercenary mujahideen into a state of religious fervor. It was conflict termination, as always, that no one catered for. The mujahideen returned to their countries after 1989 taking with them the brand of ideology that was taught to them. It also took them to fresh battlefields in Kashmir, Bosnia and Chechnya.

Through the period of the Eighties in particular and even more aggressively thereafter, the Saudi formula of spreading its brand of Islam far and wide to counter a possible rise of Shiaism from Iran’s dynamic revolution continued. While the House of Saud may have had princes and others educated in the West, their hold over the state remained only due to the carefully crafted relationship with the powerful Saudi clergy. It is this awkward relationship which has ensured the proliferation of Wahhabi Islam. Pakistan’s role in this has also been prolific, which is why it is often called the core centre of Radical Islam. This brief analysis cannot be complete without a final word on how a strategic misreading by the US possibly allowed the spread of this dangerous radical ideology.

Firstly, it was Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party which remained a bastion against Wahhabism until it was destroyed and driven to adopt a confrontationist stance which led to the emergence of a stronger ISIS, from the ranks of the Al Qaida in Iraq. Secondly, and this is conjecture more than anything else, it was the psychological and less strategic reasoning which led the US to adopt an inflexible attitude towards the Republic of Iran (the US embassy incident and the year long standoff affected US psyche more than US analysts may like to admit). The only reference I have found for this rationale (and it is open to intellectual investigation and critique) is Stephen Schwartz’s seminal book—The Two Faces of Islam. A possible rapprochement between the US and Iran was made almost impossible by the coming of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the nuclear ambitions of Iran.

It is best to leave it there without further analysis because the purpose of this piece is only to concentrate on and draw attention to the year 1979, a year which deserves to be seen as the most significant year of the second half of the twentieth century.

The writer is a former GOC of India’s Srinagar based 15 Corps, now associated with Vivekanand International Foundation and the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.