Business

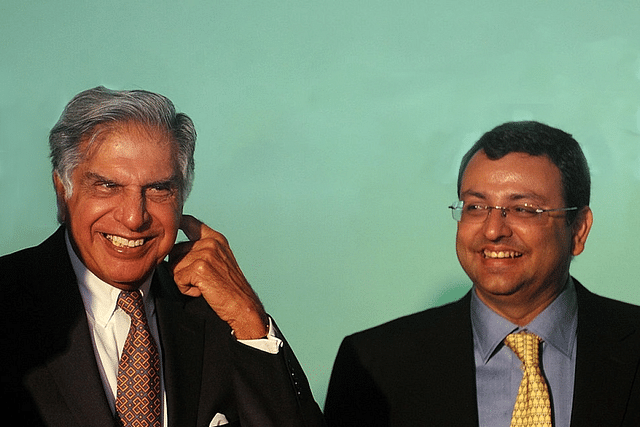

Four Questions That Pop Up As Tata-Mistry Fight Enters Final Round At Supreme Court

R Jagannathan

Jan 06, 2020, 03:19 PM | Updated 03:29 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Notwithstanding what the final outcome is in the Ratan Tata-Cyrus Mistry battle over Tata Sons, one thing is clear: the issues raised have layers that go beyond just a personality clash. The National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) order of 18 December, which reinstated Mistry at the helm of Tata Sons, has opened a can of worms. The questions that need answering are the following:

One, what is the point in foisting a minority shareholder as chairman of Tata Sons when the main shareholders — various Tata Trusts — are not in favour of his return? There is some lack of judgement here in the NCLAT order.

Two, what is a reasonable recompense that Mistry can seek after his ignominious ouster in the October 2016 boardroom coup?

Three, should charitable trusts be allowed to control shareholdings in companies, including companies in the Tata group?

Four, can a minority shareholder in Tata Sons be elbowed out of a board representation that was available to him for more than three decades?

For starters, the NCLAT order restoring Mistry’s position as chairman of Tata Sons is a remedy worse than the disease. You can’t have a chief for Tata Sons who is not acceptable to the board.

Luckily for Tata Sons, which has filed an appeal in the Supreme Court against the NCLAT verdict, Mistry is not seeking that chair. In what can only be seen as a sign of reasonableness on his part, he has clearly stated that he does not want the chairmanship; he only wants a board seat based on his group’s 18-per cent-plus shareholding in the company.

The Times of India quotes Mistry as saying: “I intend to make it clear that despite (the 18 December 2019) NCLAT order, I will not be pursuing executive chairmanship of Tata Sons, or directorship of Tata Consultancy Services, Tata Teleservices or Tata Industries.”

So, the Supreme Court should not have any problem in junking the NCLAT order that would have created needless managerial chaos at Tata Sons and other key Tata boards.

However, the second and fourth questions — reasonable recompense and representation for the Pallonji Mistry group on the board of Tata Sons — cannot be ducked. Mistry made it clear that he would not relent on this: “I will vigorously pursue all options to protect our rights as a minority shareholder, including that of resuming the 30-year history of a board seat and incorporation of the highest standards of corporate governance and transparency at Tata Sons.”

The apex court could clearly restore the board seat for Cyrus Mistry, but purely from a practical angle, he should appoint a nominee rather than accept the seat himself. A neutral outsider nominated by Mistry would be enough to take care of the group’s minority interests.

However, if the Tatas want no representative of the Mistrys on board, they have to pay them off by buying out their shareholdings — which, however, will be very expensive. The proportionate share of the Mistry group’s indirect holdings in TCS alone would be worth around $15 billion. Clearly, this cannot be decided by the court, and needs an out-of-court deal.

But the biggest question is this: should Tata Sons, a non-operative holding company of the Tata Group, be controlled by charities? Ratan Tata’s control of Tata Sons comes indirectly from his control of various Tata trusts, which collectively hold a majority stake in Tata Sons.

Swaminathan Anklesaria Aiyar, writing in The Times of India on 4 January, clearly believes that charities should not own shares beyond a small limit. He is right for two reasons:

One, charities cannot take an active interest in running corporations when their job is to run their social programmes. Making them active shareholders would defeat their core purpose of being non-profits.

Two, by owning a significant chunk of shares in a holding company, they themselves get a raw deal. Reason: the economic benefit of holding these shares gets lost in the control function they perform. Example: if the huge dividends of TCS were to be available fully to Tata charities, they would get more money than if they got only the net amounts of TCS dividends minus the amounts reinvested in the other Tata businesses.

Logically, the Tatas should use the fight with Mistry to rethink the relationship between the Tata trusts and Tata Sons. The latter can remain the key holding company of the group, but the trusts should divest their shareholdings in Tata Sons in favour of a new corporate holding company in return for a guaranteed annual payout from Tata Sons.

It is not clear if the law would allow for this transfer of ownership without inflicting huge transaction and capital gains costs on the trusts, but that is for the lawyers and accountants to decide.

Another possibility is to do what Azim Premji did with his Wipro shares, where economic ownership was substantially shifted to his charitable trusts, but control remained with him and his family.

But what is unworkable in the long run is the idea that trusts should control large conglomerates. This is unacceptable and unworkable.

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Jagannathan is Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.