Business

Five Reasons Why Some Indians Hate Capitalism And Wealth Creators

- Without being sentimental about one company, one must evaluate the irrational hatred for capitalism, especially when the same critics endlessly romanticise the industries of the West and China.

- Here are five key aspects explaining this skepticism.

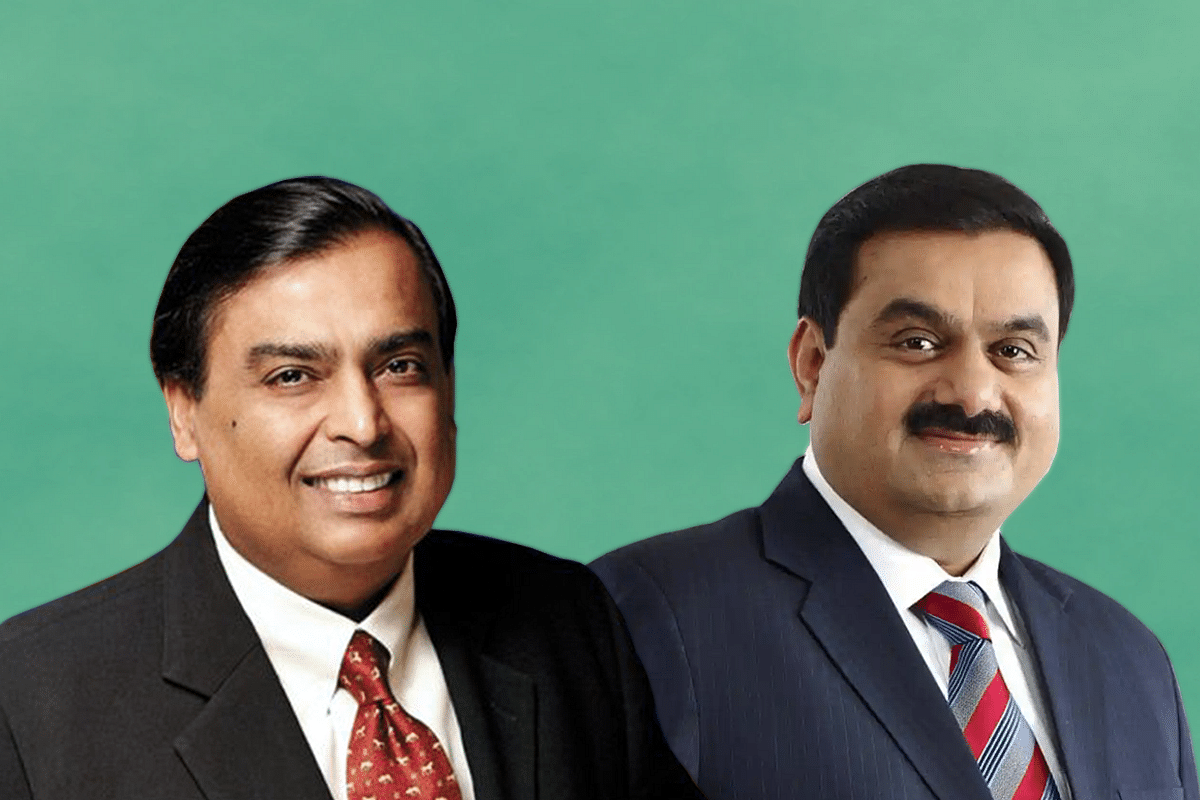

Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani.

In a country where less than seven per cent of the population willingly pays taxes, it is not very difficult to estimate the exact sentiment for and against capitalism.

When viewed from different political and social prisms, at an individual level, several conclusions on wealth creators emerge.

For the investors, it is a testament to India’s growth story. For the taxpayers, it is the roadmap for India’s future.

For the poor, at least some, it is about hope. For many, however, it is something to be viewed with deep disdain or socialist skepticism.

The last few days, the ones that Gautam Adani would want to forget, offer some clues. For some odd-reason, a short-seller driven panic attack against the Adani Enterprises was a reason for many in the opposition to glee and celebrate.

While it was Adani who witnessed most of his notional wealth being wiped out and not the investors, the crash was an opportunity for many to speculate the collapse of the Indian financial system, before being fact-checked by saner minds.

Some stated that Life Insurance Corporation (with less than one per cent exposure) would go under. Some wanted a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) to investigate the share price fall. Some went too far and declared that India’s sovereign rating could be downgraded.

More than Adani, it was about what he represented and demonising it. Without being sentimental about one company, one must evaluate this irrational hatred for capitalism, especially when the same critics endlessly romanticise the industries of the West and China.

Five key aspects explain this conservative phenomenon.

One, the hangover of Nehruvian socialism we have inherited for the last five decades.

While the Indian economy was imagined as a mix of public and private sector at the time of independence, the latter was only demonised until the government was pushed against the wall in 1991.

Furthermore, the license raj era of post-independence India was instrumental in strangling enterprises and innovation. Thus, the ‘mai-baap sarkaar’ mentality prevailed for a good part of the last seven decades.

Two, the politics. When educated taxpayers, working with leading private corporations, advocate for parties that are on an economic suicide mission, one can’t help but blame the politics of the land.

Freebies are being confused for welfare, and thus, the likes of Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), Samajwadi Party (SP), Trinamool (TMC), and many more enjoy the freedom to undermine the importance of wealth creators, even at the risk of rendering their state bankrupt or denting long-term investment and employment prospects.

Three, the mindset. The recent protests against the Agnipath programme reaffirmed the curse of the sarkari naukri mindset that puts job security and lifetime pension above merit and entrepreneurship.

In some states, young Indians were unable to accept a reform because they did not understand how to deploy four years of experience, gained in the toughest terrains and a million rupees at the age of 21-25, for their future.

What else explains post-graduate and doctorate students wasting their prime years away preparing for a government job, big or small.

Four, the urge to not evolve or innovate with the moving times.

When the three farm laws were repealed, the biggest losers were the farmers of Punjab, who by virtue of their geography, land holdings, and relatively better education and exposure to the urban environment, could have benefited from the collaboration with the private sector.

Yet, they clogged a national highway for almost a year to stick to the MSP regime, knowing that the ecological time-bomb was ticking.

Put simply, many don’t wish to learn how to fish, but want one supplied to them each morning.

Five, a lack of understanding of how capitalism works. America and China, even while being two extreme ends on a political spectrum, have supported the cause of the home-grown enterprises in many legitimate ways, from Microsoft to Huawei.

However, only in India do people frown upon the prospect of a local or national government backing a wealth creator. For many, the mere idea of a national government lobbying for an able private organisation in a foreign land is criminal.

This lack of understanding of capitalism also explains why BSNL could never go on to become a Huawei-equivalent.

It will not be an exaggeration to say that Indians, perhaps, are the biggest hypocrites when it comes to wealth creation.

Most want ideal infrastructure, better amenities, and a booming economy, but they do not want the private sector to play a key role in it.

Most want the farmers to prosper, but do not want the high-income-farmers to pay any tax or go private.

Most want employment to be created, but want the manufacturing sector to not boom and for the government to keep churning out nine-to-five jobs.

Most want the government to undertake every welfare policy, but do not want the same government to have a steady stream of tax revenue.

The Adani episode leaves an opportunity for many to introspect about how they view capitalism and wealth creation.

The company will course correct, as most do. The share price will correct itself, as it often does. The enterprise will bounce back, as most do.

However, it is important for Indians to discard their disdain for the private sector that will be instrumental in the five-trillion-dollar economy pursuit.

Beyond everything else, one must remember that flourishing economies are not built by companies that take six-months to install one landline telephone, by farmers that kill the ecology for subsidies, by youth who idle away their years in UPSC attempts, and by parties that believe in buying voters rather than catering to their long-term interests.

India needs private sector as much the private sector needs the Indian market; probably more.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest