Ideas

Breaking Free: Decolonising Education Through Indian Knowledge Systems

Jyotirmaya Tripathy

May 04, 2024, 05:15 PM | Updated 05:15 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

This writer has written previously about the need for mainstreaming Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) or Bharatiya Gyan Parampara (BGP) in the university system that acknowledges the reality of India as a cultural and economic powerhouse.

The naysayers would still demand to know if there is any structuralist principle that connects disparate disciplines and domains under the umbrella term IKS. The easy way to respond to them would be the refusal to find such a principle.

Do we worry when operations research, finance, psychology (and more) come together to offer a management programme? Or, for that matter, when engineers, economists, and governance and law scholars come together to offer a public policy programme?

Bharat As Gyan Bhumi

A mature and substantive response, however, would be to acknowledge the question and explore an intellectual fibre articulating the foundations of IKS.

As this writer sees it, the key word in IKS is ‘Indian’ or ‘Bharatiya’. The disciplines falling under the IKS template are governed by an Indian way that studies aesthetics, architecture, astronomy, grammar, mathematics, philosophy, political economy, and different kalas and vidyas using India as a reference point and seeing this land as the locus of knowledge.

One does not have to be jingoistic to believe that the earliest treatises on poetry, prose, grammar, mathematics, medicine, and their codification were produced in India. That means IKS is a set of attitudes, a way of seeing and believing that acknowledges India as gyan bhumi (land of knowledge).

It involves a recognition that India was home to countless intellectual traditions and knew how to explain and organise human experience. Our capacity to survive and resist assimilation after centuries of subjugation was due to that awareness. Thousands of years after their origin, the traditions continue to be the key to our survival as a unique civilisation.

Its recognition today and the concomitant self-discovery of the scholar are not a narrow exclusivist agenda of delegitimating other ways of knowing. Rather, it is a demand for recognition. An experiment with IKS stirs that collective memory and makes a dash for experiencing India as an intellectual geography.

The Indian way is the recognition of India as a gyan bhumi that not only produced great art, architecture, sciences, and engineering, but also created knowledge texts that continue to guide contemporary life. This reality interrogates the idea that India is merely an object of knowledge, but not a knowledge producer.

The second condition is to understand India as a historically continuous civilisation that is intrinsically connected to sacred spaces. This way of thinking challenges the notion that Indian civilisation was a mere palimpsest and any effort to engage with ancient texts would be revivalist.

The third condition is the acknowledgement that the Indian core values (sacrality of land, centrality of family in shaping cultural behaviour) have not changed over centuries, something that demonstrates not just the resilience of its people, but also its inherent strength to withstand any disruption.

This idea questions the assumption that India as a cultural unit does not exist or that India is a perpetual contradiction in terms of its unredeemable caste and religious conflicts.

The fourth condition is the continuing relevance of Indian knowledge traditions after centuries of evolution, invasions, and colonialism. These traditions come in multiple hues and are sufficiently reflexive to absorb criticism, thereby challenging the notion that Indian knowledge texts are remnants of a bygone era.

A fifth condition, perhaps, would be a nuanced engagement with knowledge coming from the West instead of dismissing it lock, stock, and barrel. Over centuries, many scholars from outside India have studied India and its people with a sensitivity that many Indian scholars are not capable of.

This experience contradicts the idea of the West as a monolith and presents to us the other West, one that does not believe in its soul-denying principles, history of plunder and domination, not to mention its decadence and culture of individualism.

This would mean a productive conversation between divergent traditions coming from various parts of the world in a spirit of mutual respect and understanding.

As and when Western ideas (including those that ape the Orientalist mode) come to us, our default response should be of critical engagement rather than meek surrender or outright rejection. To the extent possible, our effort should be to use Indian vocabulary and avoid research that is derivative of Western models. The difference between the social participant and the social observer is thus closed, and the latter is not privileged over the former.

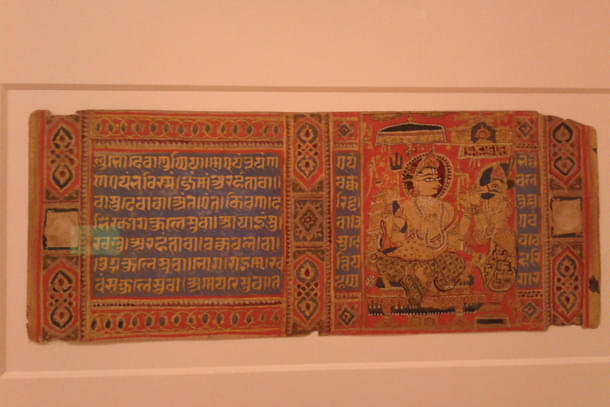

As tirtha kshetras produced an idea of India as a sacred geography and brought various parts of the country together through interconnected mandalas, Indian thinkers and practitioners, spanning over more than 3,000 years, created a knowledge society — an India that is deliberative and reflective.

In this endeavour, they not only engaged with earlier scholars, but also advanced and even interrogated their predecessors. The conversation between Nachiketa and Yama, Yajnavalkya and Maitreyi, Svetaketu and Uddalaka prove beyond doubt that Indians were seekers (including women and children) and were ready to push the limits of knowledge by constant probing.

As Kapil Kapoor explains, Hindus, not being of a monotheistic religion and being unfamiliar with the practice of deifying books, had the intellectual agility to interpret, question, and modify tracts written before them.

Anyone familiar with India’s aesthetic tradition would know how Anandavardhana, Bhatta Lollata, Sankuka, and Bhatta Nayaka differed in their understanding of rasa. That meant there was no unquestioning acceptance of what came before.

There was also an awareness that some schools or individuals belonged to the navya or new, in contrast to what was pracina or old. Jagannatha, Siddicandra, and Appaya Dikshita, among others, shook the traditional foundations of rasa and alamkar.

Various schools of aesthetics offered continuous, unbroken and, more importantly, cumulative knowledge where every new text added to the preceding text, a tradition that unfortunately saw signs of decay after independence.

The Quest For Swaraj

In significant ways, IKS can alter the way we know India and, by implication, understand ourselves. More than any other period, not even during Islamic or colonial rule, which no doubt saw the stagnation of ideas, the post-independence period has been notoriously culture- and knowledge-denying.

During this period, the West stood for the universal and India for the particular, that too a deviant one. Ironically, the civilisation that denied us our experience by forcing us to look at ourselves through a foreign mirror was legitimated as the only objective way of knowing India.

It was not the India that Indians knew; it was a phantasmatic India, a construct, a shadow that reduced India to data and subjected its analysis through a Western lens.

Unlike earlier Orientalists and missionaries, this time Indians themselves started believing in the West’s superiority and universality. Political independence in 1947 ran parallel to intellectual subjugation. We can break free from this impasse by saying no to the West’s universality as a reference point for Indian problems.

That is the first step to knowing our land and a potent path to our sense of self to become an Indian. An experiment with IKS is a perpetual becoming, of becoming Indian 75 years after political independence.

In recent times, we have heard from academics (and also cinestars) that India did not exist prior to 1947, and so any effort to recreate that illusion through our investment in IKS is detrimental to the country’s secular character. If knowledge of our itihasa and the awareness of historical facts can create such historical platitudes so as not to endanger the secular fabric, the country’s constitutional foundation is indeed weak.

In 1888, Sir John Strachey, a British Indian civil servant, argued while introducing India to trainee civil servants: “The first and most important thing to learn about India is that there is not and never was an India.”

Today’s secular-minded historians (the authors of A New History of India) believe India came into existence with the arrival of Mughals. For these ‘eminent historians’ (to use Arun Shourie’s expression), India was just a geographical expression. India, thus, was an empty signifier that can be filled by anyone (except those who believed in its intellectual and sacral nature) with any meaning.

Diana Eck rightly observed, “In the past three centuries, India has been seen by traders as a source of riches, by rulers as a part of empire, by missionaries as a mission field for winning souls, by romantics and seekers as the source of something missing in the heart and soul of the West.”

Both pre- and post-independence India saw the country as a fallen land to be rescued by colonial administrators and post-colonial leaders and academics.

Ironically though, Jawaharlal Nehru (not a great believer in India’s intellectual traditions) in his letter to Chinese Premier Chou En-lai in 1963 would invoke scriptural sanction (quoting from the Rig Veda and Vishnu Purana) for India’s sovereignty over the Indian side of the Himalayas.

Borrowing from Eric J Sharpe, Arvind Sharma refers to the ‘response threshold’, a condition wherein the believer can promote his own interpretation against the scholar. In the contemporary context when the subject of discussion involves an understanding of the present, the cultural insider can offer a pushback, a legitimate one at that, to that of the Western or Indian Orientalists.

An experiment with IKS will complicate the difference between the social participant and social observer, and create enabling conditions for Indians to create their own response threshold. That would also mean producing theory through analyses of cultural practices and not by importing them from elsewhere.

That should lead to, in due course of time, not just engagement with IKS in a conventional sense, but expanding or transforming the way standard disciplines like sociology or political science are taught. That would involve mainstreaming Indian political and sociological experiences and finding Indian theoretical equivalence for explaining Indian problems.

Mainstreaming IKS is that disruptive moment in academic history when we have a realistic chance to decolonise education and ourselves.

Almost 100 years ago, philosopher K C Bhattacharya cautioned us against cultural subjection “when one’s traditional cast of ideas and sentiments is superseded without comparison or competition by a new cast representing an alien culture.” When one has the conviction to shed a “slavery of spirit,” one experiences rebirth, a Swaraj of ideas.

This is not to deny everything that is positive about the West, but to assess, question, and adapt if required. The problem occurs when our education does not equip us to interrogate what we receive from outside the way we are taught to interrogate our own values.

Foreign ideas come to us through nicely packed social science curricula at a time when we have lost the window to our own cultural and moral universe. When we have lost our Indian mind and are not even aware of that reality, Western training comes to us as the only model to understand our reality and paralyses us in the process.

In this scheme of things, even an open-minded discussion of our IKS may appear as an experiment with the archaic. Bhattacharya was prophetic when he said Western education has not helped us understand ourselves, nor understand the relevance of our past, nor its promise for the future.

Taking a cue, it would be safe to believe that IKS is an antidote to these externally imposed values.

Also Read: Mainstreaming Indian Knowledge Systems Marks A Paradigm Shift In Educational Institutions

Jyotirmaya Tripathy is Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Madras. Views expressed are personal.