Politics

West Bengal Has 1.04 Crore Excess Voters As Per This Demographic Reconstruction Research

Prof. Vidhu Shekhar and Prof. Milan Kumar

Aug 12, 2025, 08:35 AM | Updated Sep 01, 2025, 03:30 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

![Voters in West Bengal. [Representative Image]](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2025-08-11/t448gqiq/Bengal-excess-voters.jpg?w=610&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

![Voters in West Bengal. [Representative Image]](https://swarajya.gumlet.io/swarajya/2025-08-11/t448gqiq/Bengal-excess-voters.jpg?w=310&q=75&compress=true&format=auto)

For a democracy to function, the legitimacy of its elections depends first and foremost on the accuracy of its voter rolls. If the list of who can vote is swollen with names that no longer correspond to real, eligible residents, the very foundation of electoral integrity is at risk.

Unfortunately, West Bengal’s voter reality does not reflect this. Our study, Electoral Roll Inflation in West Bengal: A Demographic Reconstruction of Legitimate Voter Counts (2024), which uses rigorous demographic accounting grounded entirely in official data to reconstruct West Bengal’s legitimate electorate, finds that West Bengal has 1.04 crore voters too many.

The figures emerge from a reconstruction exercise that relies only on official datasets, including past electoral rolls, census-derived age profiles, survival rates, births, and net migration figures. We start with a verified baseline roll, project how it should change over two decades given births, deaths, and migration, then compare it to the Election Commission’s current list.

The result gives a gap so large that it would, on average, add more than 35,000 unverifiable entries to each assembly constituency. In many elections, even those not close, that margin is enough to tilt the scales.

Before exploring the implications, it is necessary to understand the process and methodology of demographic reconstruction undertaken in the research to arrive at the figure.

Reconstructing the Electorate

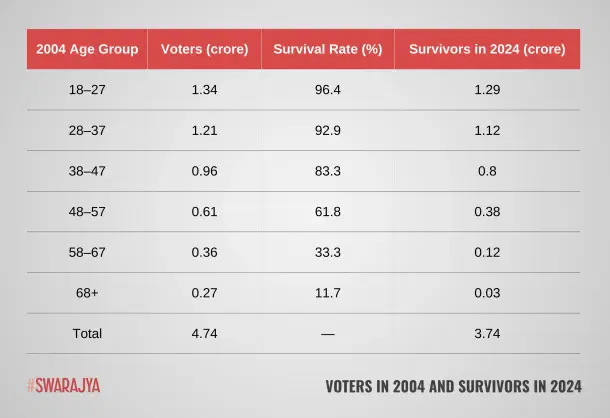

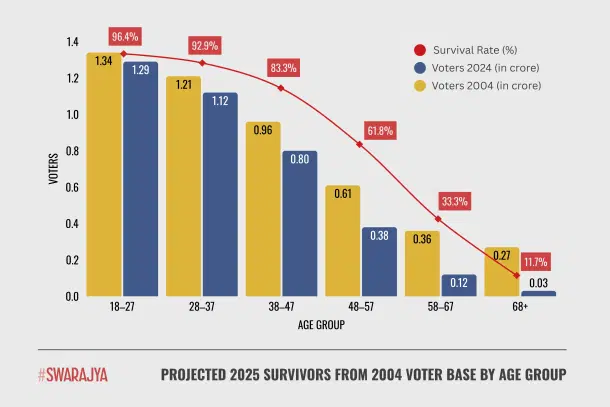

Our starting point is the 4.74 crore registered voters on the 2004 electoral roll, which was used for voting in the 2004 General Election. This voter list was chosen because it was the available official voter count after the 2002 intensive revision of the voter roll in West Bengal and therefore served as a reliable baseline.

Step 1: Ageing the 2004 roll

In the first step, we divided the 2004 voters into age cohorts. We used age distributions from the 2001 Census, aged each cohort forward by three years to align with 2004, and then applied official survival probabilities from the Sample Registration System life tables to account for deaths in each group.

This yielded the age-cohort-wise breakdown of the 2004 electoral roll. We then aged these cohorts forward another 20 years, again applying survival probabilities, to estimate how many of the 2004 voters would still be alive in 2024.

As expected, survival rates are much higher for younger cohorts, for example, 96.4% for those aged 18–27 in 2004. They are far lower for the oldest, with only 11.7% of those aged 68 and above in 2004 (88+ by 2024) still alive.

From the original 4.74 crore, about 3.74 crore would be alive and eligible today. This survivor count is the first building block of our estimate.

Step 2: Estimating new voter additions (1986–2006 birth cohorts)

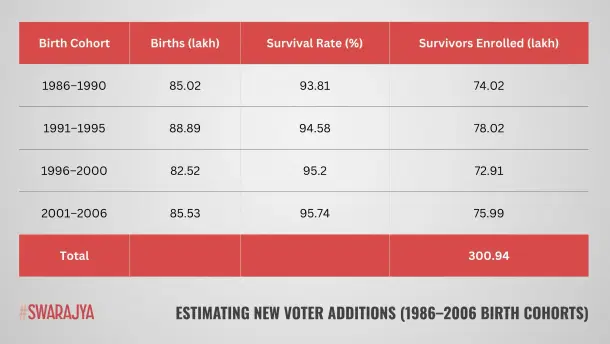

The second stage of the reconstruction is to account for citizens who turned 18 and became eligible to vote after 2004. This covers those born between 1986 and 2006, who would have reached voting age between the 2004 General Election and the 2024 roll.

For each birth year in this range, we used annual birth estimates from the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, which in turn are based on crude birth rates applied to state-level population figures.

These birth cohorts were then subjected to age-specific survival probabilities from the Sample Registration System life tables, allowing us to estimate how many members of each cohort would still be alive in 2024.

We then applied a 92.8% registration rate, deliberately higher than the historical 91.3% (2004) and 91.8% (2011), to err on the side of overestimating legitimate voters. This conservative bias makes our excess figure a lower bound.

This computation was done year by year for all 21 years in the range 1986–2006. For ease of presentation, we aggregate the results into five-year blocks.

On this basis, we estimate that approximately 3.01 crore new voters joined the electoral rolls between 2004 and 2024. These additions form the second building block of our reconstructed legitimate electorate.

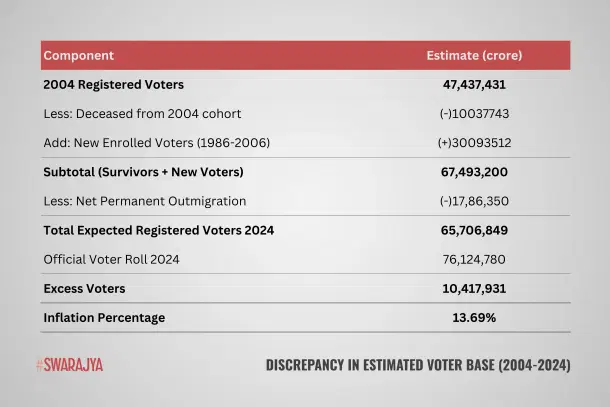

Adding the survivors from the 2004 roll to the new voter cohorts gives a combined total of 6.74 crore. This figure is calculated without deducting for any migration or other eligibility losses. It reflects only the effects of births and deaths. Even on this generous basis, the total remains well below the official 2024 electorate of 7.61 crore.

Step 3: Adjusting for net permanent migration

The final stage adjusts for permanent migration. West Bengal has been a consistent net outmigration state for decades, with working-age adults moving out for employment and education opportunities in other states.

We used Census migration data for 2001 and 2011, which records those whose last usual residence was outside their current state for over one year, the standard threshold for permanent migration. We calculated compound annual growth rates for both outmigration and in-migration flows, then extrapolated to 2024.

The negative in-migration figure reflects West Bengal’s declining attractiveness. The number of people from other parts of India residing in the state has declined over the years according to census figures.

Between 2004 and 2024, West Bengal lost approximately 18 lakh voters to net permanent migration. This estimate is conservative, as post-2011 outmigration to high-growth states such as Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Karnataka appears to have accelerated, but our model assumes steady linear growth rather than the likely sharper increase.

Putting the pieces together

With the three building blocks in place, namely survivors from the 2004 roll, newly eligible voters from the 1986–2006 birth cohorts, and the adjustment for net permanent migration, we can now estimate the legitimate voter population of West Bengal in 2024.

It is important to stress that every assumption in our reconstruction errs on the side of overstating the legitimate electorate rather than understating it. The 2004 roll is treated as fully accurate, the registration rate for new cohorts is set higher than historically observed, and migration is projected at a steady rate without factoring in the probable post-2011 acceleration in outmigration.

Even with these generous assumptions, the result still shows more than one crore names on the roll with no demographic basis. This 13.69% inflation should therefore be seen as a lower bound. The actual level of excess registration may be even higher.

A roll too full for democracy’s good

An electoral roll is not just an administrative list. It is the starting line of democracy. When that list carries more than a crore names with no demographic basis, it is not a harmless error. It is a structural weakness.

West Bengal’s rolls have gone more than two decades without a comprehensive, door-to-door verification. The result is a register that has drifted far from demographic reality, inflating the denominator on which turnout, representation, and legitimacy rest.

The solution is not cosmetic tinkering but a full Special Intensive Revision supported by ongoing demographic audits that reconcile rolls with death registrations, migration records, and credible identity verification. Without this, the gap between the official roll and the real electorate will only widen, eroding trust in every future contest.

In a state where political margins are often measured in thousands, the stakes of ignoring this inflation could not be higher. Every election conducted on these rolls operates with a foundation that cannot withstand demographic scrutiny.

Note: The authors would like to acknowledge the Economic Truth Initiative (@Finskeptics) for providing analyst support in data gathering.

Also Read: Bihar Has 77 Lakh Excess Voters As Per This Demographic Reconstruction Research

Dr. Vidhu Shekhar is currently a Faculty member at Bhavan's SPJIMR, Mumbai. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from IIM Calcutta, an MBA from IIM Calcutta, and a B.Tech from IIT Kharagpur. Dr. Milan Kumar is currently a Faculty member at the Indian Institute of Management Vishakhapatnam. He holds a Ph.D. from IIM Calcutta.