Politics

Bihar Has 77 Lakh Excess Voters As Per This Demographic Reconstruction Research

Dr. Vidhu Shekhar and Dr. Milan Kumar

Jul 12, 2025, 12:30 PM | Updated Aug 03, 2025, 09:44 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

What if an entire city, say Pune, vanished from India’s map, yet its residents continued casting votes in every election? This is not a thought experiment. It is Bihar’s electoral reality.

Our study, Demographic Reconstruction and Electoral Roll Inflation: Estimating the Legitimate Voter Base in Bihar, India (2025), uses rigorous demographic accounting grounded entirely in official data—vintage electoral rolls, age-specific survival probabilities, birth cohort estimates, and net interstate migration—to reconstruct Bihar’s legitimate electorate.

The finding is stark: 77 lakh names on the state's current voter list cannot be explained by any demographic logic.

These are phantom voters, untraceable through demographic reasoning, yet fully present in the democratic electoral ledger.

As of July 2025, the Election Commission lists 7.89 crore registered voters in Bihar. Our reconstruction puts the true eligible population at 7.12 crore, implying an inflation of 9.7 percent, an average of more than 30,000 excess entries per constituency, with likely pockets of far more severe distortion.

In a state where electoral margins are razor-thin, such inflation has real consequences. The 2020 Bihar Assembly election was the closest in the state’s post-independence history: nearly 20 percent of all seats, the highest share across 14 assembly cycles, were won with a margin under 2.5 percent. Seventeen of those were decided by less than 1 percent.

In such an environment, the presence of unverifiable names is a grave democratic fault line. Inflated rolls are active enablers of distortion, opening the door to fraud, false turnout narratives, and illegitimate mandates.

Reconstructing Bihar’s Legitimate Voter Base

To estimate the true size of Bihar’s eligible electorate in 2025, we carried out a three-step demographic reconstruction rooted in publicly available data. Each step was executed rigorously: estimate how many 2003 voters are still alive, add the number of new eligible voters since then, and subtract those who have permanently left the state. What emerges is a data-backed correction to the official voter roll.

Step 1: Estimating Survivors from the 2003 Voter List

Any credible reconstruction of Bihar’s legitimate electorate must begin with a voter roll that reflects administrative integrity. The year 2003 offers precisely that, when the Election Commission carried out a Special Intensive Revision (SIR), a door-to-door verification of voters. In contrast, the years that followed saw summary revisions without comparable diligence or consistent pruning of the deceased, the migrated, or the duplicated.

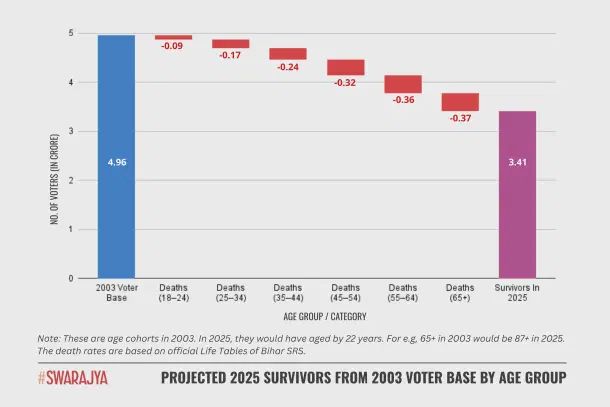

The 2003 roll recorded 4.96 crore voters. Unfortunately, like most Indian rolls, it did not record age. To estimate how many of those voters are still alive, we used the 2001 Census to derive an age distribution, aged each group forward to 2025, and applied official life-table survival rates from the Sample Registration System. These official life tables allow us to model cohort-wise mortality with demographic precision.

As expected, survival probabilities fall steeply with age. Among voters who were aged 18 to 24 in 2003, over 90 percent are likely to be alive in 2025. For those aged 65 and above in 2003, fewer than one in fourteen are expected to survive.

The result: of the 4.96 crore people on the 2003 roll, only 3.41 crore are likely to be alive in 2025. The full cohort-wise breakdown is presented below:

This estimate is built entirely from official demographic data and forms the first foundational pillar of Bihar’s legitimate electorate, accounting for biological reality.

Step 2: Estimating New Voter Additions (1985 to 2007 Birth Cohorts)

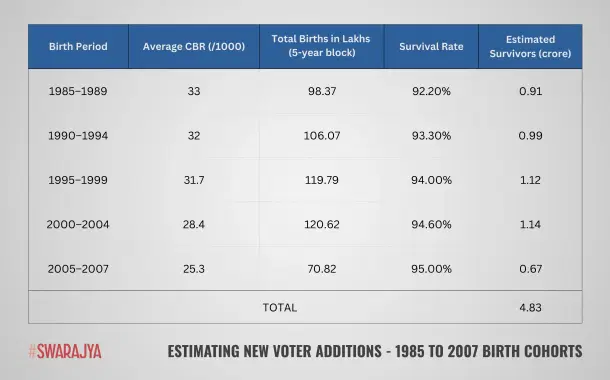

The second pillar of our reconstruction involves estimating how many new voters became eligible between 2003 and 2025 due to turning 18 years old. This calculation covers individuals born between 1985 and 2007.

To estimate their numbers, we began by calculating the size of each birth cohort using official demographic data. This involved applying Crude Birth Rates (CBRs) from the Census of India, the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), and the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence to estimated annual population figures for Bihar. We then accounted for mortality in the cohorts by applying Bihar-specific age-related survival probabilities.

While we did this for each year from 1985-2007, a summary age-bracket-wise table of findings is presented below:

The analysis estimates that approximately 4.83 crore individuals born between 1985 and 2007 will be alive and eligible voters in Bihar in 2025. This figure robustly captures the demographic reality of new electoral participation over the stated period.

Step 3: Adjusting for Permanent Net Outmigration

Migration is the third, and most neglected, pillar of electoral accuracy. Bihar has long been a high outmigration state. Ideally, voters permanently settled outside the state should no longer appear on Bihar’s rolls, but deletions rarely happen unless voters voluntarily initiate them.

To estimate this effect, we utilised detailed migration data from the 2011 Census, focusing on adult interstate migrants who had resided outside Bihar for more than one year, effectively capturing permanent migrants ineligible to vote in Bihar.

From 2011 Census data, we identified migrants residing outside Bihar for periods between one to four years and five to eight years. These two categories totalled 49.65 lakh permanent adult outmigrants from 2003 to 2011, translating to an annual migration rate of roughly 5.5 lakh individuals.

For the subsequent period from 2012 to 2025, we conservatively assumed that this annual migration rate remained unchanged, even though structural trends suggest migration may have accelerated. Applying this constant rate gives us 72 lakh additional permanent outmigrants over the 13-year period from 2012 to 2025.

As for people who moved into Bihar, we included the entire 8.8 lakh estimated permanent inward migrants, even though many are likely temporary workers or dependents.

Inward migration to Bihar remains minimal. We used the 2011 Census figure of 7.06 lakh interstate migrants residing in Bihar as a proportion to estimate approximately 8.8 lakh inward migrants in 2023. Even though many of these might be temporary residents, we cautiously considered all as permanent.

This gives us a net permanent outmigration of 1.12 crore individuals between 2003 and 2025 who should no longer be eligible to vote in Bihar.

- Permanent out-migrants from 2003 to 2011: 49.65 lakh

- Permanent out-migrants from 2012 to 2025: 72.00 lakh

- Less inward migrants: 8.80 lakh

- Net permanent outmigration from 2003 to 2023: 1.12 crore

This deliberately conservative figure assumes stable migration rates and fully permanent inward migration.

Final Estimate: Phantom Democracy by Numbers

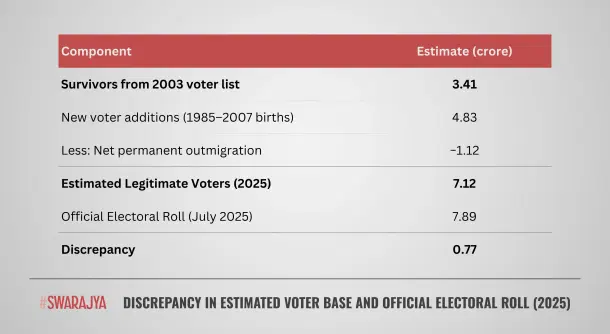

When we combine all three components of the reconstruction, i.e, the survivors from the verified 2003 voter roll, the eligible additions from post-2003 birth cohorts, and the adjustment for permanent migration out of Bihar, we arrive at a stark numerical reality:

The discrepancy of 77 lakh excess voters is not a statistical quirk. It is the result of faulty inclusions, structural inertia, institutional gaps, and a lack of automated purging mechanisms. The numbers translate into something very tangible at the constituency level.

Most assembly constituencies in Bihar have between three and four lakh registered voters. A distortion of 77 lakh across the state implies that 25,000 to 50,000 entries per seat could be phantom. In tightly contested races, this margin is not incidental; it is often decisive.

The consequences ripple through every layer of the democratic process. It alters voter turnout calculations, distorts the denominator in representation ratios, and opens the door for manipulation, particularly through double registration or fraudulent ballots. Moreover, it weakens the legitimacy of mandate claims and undermines public confidence in the electoral machinery.

This is not a data anomaly. It is a democratic fault line. The accuracy of a voter roll is a foundation on which electoral legitimacy rests. Bihar’s bloated rolls are a mirror reflecting deeper systemic failures. The question is no longer whether there is a problem. It is whether there is political and institutional will to fix it.

The Ledger of Democracy Must Be Fixed

Our analysis identifies 77 lakh names on Bihar’s rolls that cannot be justified by births, deaths, or continued residence. This finding is not opinion-based. It emerges from rigorous demographic analysis built entirely on official data and conservative assumptions.

One gap is the absence of an automatic mechanism to remove voters who permanently migrate out of state. Form 8 exists for voter deletion, but relies entirely on voluntary compliance, something few voters initiate. Election officials seldom act without formal requests, and no mechanism systematically tracks interstate migration.

This oversight permits voters to remain registered simultaneously in multiple states. Individuals who relocate, for instance, from Patna to Pune, frequently appear on both voter rolls.

Other institutional weaknesses further inflate rolls. Urban slums, marked by high mobility and weak documentation, are particularly prone to unverifiable enrolment. So are border districts, where administrative oversight is thinner and the risk of inclusion of undocumented international migrants is real and persistent. These known vulnerabilities persist without effective resolution.

Collectively, these issues have distorted voter rolls, pushing them far from demographic reality. The perceived high voter enrolment masks a proliferation of ghost entries and duplicates, affecting electoral outcomes and eroding public trust.

This is not just a Bihar problem. States such as West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and others exhibit similar patterns and inadequate voter roll management. If Bihar’s rolls are inflated by nearly ten percent, the national implication is potentially millions of excess entries.

The Election Commission’s ongoing Special Intensive Revision in Bihar is a step in the right direction. It has been long overdue since 2003. However, if this revision is conducted with loose standards, weak verification protocols, relies only on passive administrative declarations, or accepts suboptimal documents as proof of citizenship, it will fall short.

For instance, Ration Cards, which have been known to be forged in the lakhs in several states, cannot be treated as reliable identifiers. Aadhaar, which was never intended to verify citizenship and has been repeatedly linked to enrolment frauds, is also insufficient. A credible voter list cannot be built on such documents.

Effective reform demands field verification, integration of death and migration records, and legislation mandating automatic removal upon death or relocation.

An election begins not when votes are cast, but when voter rolls are compiled. If the rolls themselves are inflated, the legitimacy and value of every vote is compromised.

The integrity and credibility of India’s democracy depend on clearing this anomaly and fixing the foundational ledger.

Note: The authors would like to acknowledge Economic Truth Initiative (@Finskeptics) for providing analyst support in data gathering.

Dr. Vidhu Shekhar is currently a Faculty member at Bhavan's SPJIMR, Mumbai. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from IIM Calcutta, an MBA from IIM Calcutta, and a B.Tech from IIT Kharagpur. Dr. Milan Kumar is currently a Faculty member at the Indian Institute of Management Vishakhapatnam. He holds a Ph.D. from IIM Calcutta.