Culture

Beyond Secular Cities: Temples As An Urban Experience

- The transition of the city from the abode of Gods to the space of reason and money is a recent phenomenon that was guided by the advent of industrialisation, instrumental modernity, and mercantilism.

- However, this supposed contradiction of urban life and religion, even in modern Western cities, is more of a convention (or even convenience) rather than any field-based evidence.

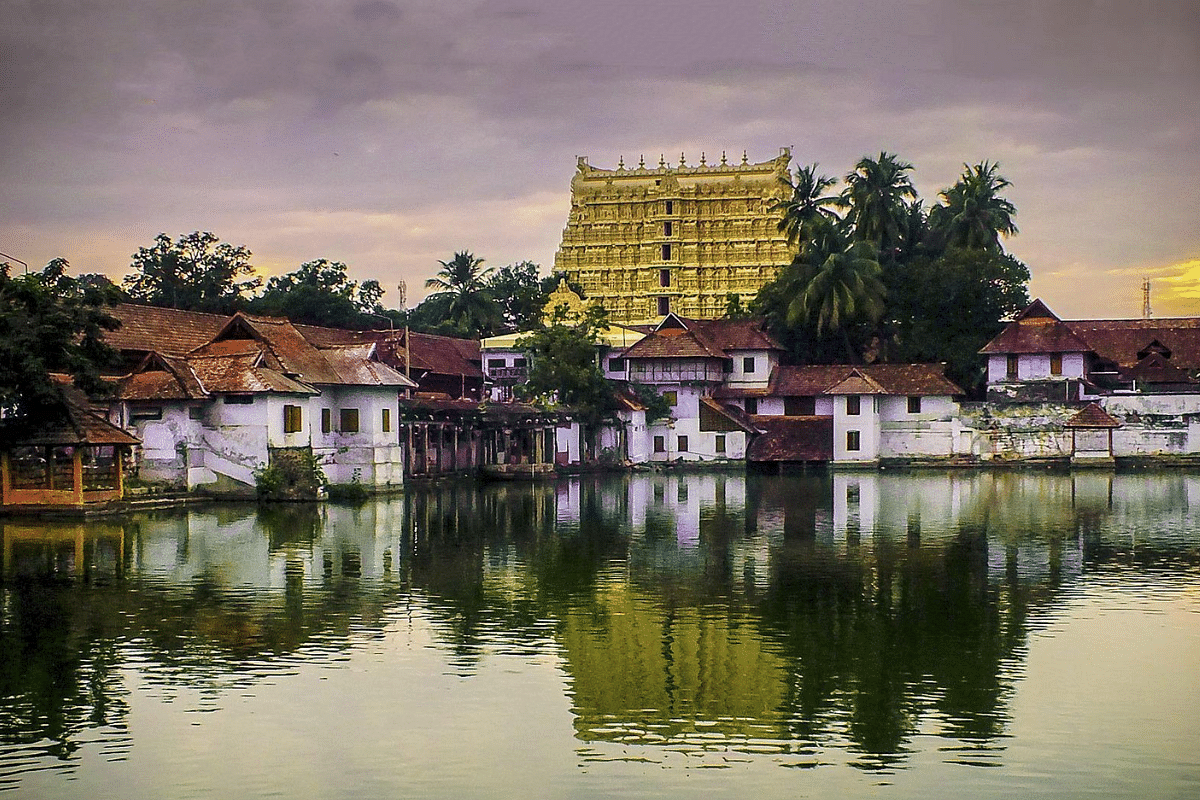

Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala

Today “the city” is seen as a manifestation of human reason, where agentic rational humans come together to build spaces for optimising resources, creating conveniences for a meaningful life, and generating surplus.

Since economy and rationalisation are the justificatory principles for a modern city, more often than not, a city is often represented as “Godless” — secular at best and rootless at worst.

In popular imagination, this idea of the city gets bolstered through its association with money, upward mobility, crime, and individualism — a space of transgression, where cultural and communitarian values are compromised.

The Tamil expression Kettum pattinam ser (if ruined, go to the city) captures this sentiment. Though it is not exactly a comprehensive rejection of the city, it does betray an uncertainty around the city as the locus of fulfilment and highlights its deceptive character as well as the alienation and ennui that follow.

A False Binary

The binary of city and God (and by extension of reason and faith), however, is not necessarily a historical fact. From the dawn of civilisation, cities have always had a metaphysical, if not strictly religious, foundation and were, in fact, the source of legitimation that created predictability to human actions.

Whether Mesopotamian, Greek, Chinese or Indian, cities were in perpetual quest for order or supreme reason that could lead to sets of justifiable beliefs and actions. In fact, the gods had a close relation with the city dwellers and often took part in the city’s cultural, political, and religious activities. The city walls often carried within them both temples and forums.

The transition of the city from the abode of Gods to the space of reason and money is a recent phenomenon that was guided by the advent of industrialisation, instrumental modernity, and mercantilism. However, this supposed contradiction of urban life and religion, even in modern Western cities, is more of a convention (or even convenience) rather than any field-based evidence.

For India’s first prime minister, the city was the externalisation of his grand modernist and secularist vision. It symbolised the coming of age for India, both as a territory and as a category of thought. In his scheme of things, the village and Gandhian ideals were India’s past; the future was not just the city but also Nehru himself as a model of modern subjectivity.

Announcing the foundational principles of Chandigarh, Nehru had declared: “Let this be a new town, symbolic of freedom of India unfettered by the traditions of the past ... an expression of the nation’s faith in the future.” Such articulations created conditions not just for statist celebration of planned geography, but also displayed the hubris of an unapologetic moderniser.

Nehruvian thinking on cities as products and producers of modern India as opposed to faith-ridden rural India guided institutional thinking and almost legitimated the binary of city and religion.

The fact of the matter is that the binary never really worked. As we know, people are not thrown into cities as modern secular subjects, but move over a period of time carrying traces of their cultural values. It is no wonder that India continues to remain the oldest continuing civilisation where life still revolves around temples, its rituals, and festivals.

Settlements and homes are still built around temples and everyday life is guided by it even when we speak of cities in states such as Tamil Nadu that have been under atheist politics for the last 50 years.

Chennai offers that uniquely intriguing experience. Often described as the gateway to South India and a cultural city, it has also been the site of anti-Brahmin, anti-Hindi protests threatening the idea of postcolonial nationhood. Due to the Dravidian political dispensations since 1967 (and even before that, through its social movements), Chennai for an outsider remains an enigma where the polity that declares itself atheist controls Hindu temples and their constant supply of donations.

That said, for city dwellers, more so for Tamil-speaking ones, this simultaneous rejection and appropriation of Hindu religious and charitable organisations offers an ironic compromise where ‘religion as practice’ is replaced by ‘religion for state’ as bountiful Kamadhenu. In this polity, religion is bad as faith, but good for economics.

The resources of the temples, thus, feed an ever-expanding wing of atheism bordering on demonisation of faith. If temples are still recognised in a tokenistic manner in an official letterhead or as an emblem, it is because temples have good aesthetics and can offer opportunities to promote the city as a destination for foreign investment due to its ‘culture’.

The City Beautiful

Singara Chennai is a case in point. It was the pet beautification project of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) government, introduced in 1996 in view of the information technology (IT) boom around the Old Mahabalipuram Road and later revived in 2021.

In its earlier avatar, the project focused on infrastructural development, particularly maintaining cleanliness and building flyovers. The aspiration was to make Chennai a Singapore, at least as a performative strategy.

The second avatar continues with cleanliness, but seeks to leverage the city’s coastline and its vibrant culture. However, the project remains a far cry from its desire of a Chennai free from garbage and wall posters, access to drinking water and toilets, popularisation of non-motorised transport, creation of space for children, elderly, and the disabled, and so on.

As per the plan, the city will promote culture through Chennai Day and Chennai Sangamam and heritage structures will be preserved. These developments will launch Chennai to the same status as other global cities, and will help attract foreign capital. New municipalities such as Tambaram, Kancheepuram, and Kumbakonam will be upgraded to corporations.

These are laudable goals, no doubt, but the heritisation of the city as tourist attractions or their aestheticisation are intended as secular exercises and, so, ignore a glaring reality; that is, the city’s deracination and elision of its religious spaces such as temples (that connects the present with the past) as living entities and organic presence.

Though heritage and culture are cited as sites of intervention, temples are not exclusively chosen other than appearing in some road signs or name boards. What explains this elision? Why does city planning leave out its temples as sites of belonging and believing? What, then, constitutes city experience outside of its temples?

Here is the dilemma: the institutional notion of the city as secular and the everyday notion of the city that runs around temple festivals and mada streets.

There are more than 600 functioning temples, and that number is growing. Every other day, there are processions of deities, kumbhabhisheks for new temples, or temple festivals spilling over to the city roads. Should we see this temple-building spree as a reaction of the middle class against state atheism? With all probability, the number of temples has gone up along with economic progress. That means people see urban experience increasingly through religion and temples. There is no evidence of the demise of religion among the educated and secular class in urban spaces.

Joanne Punzo Waghorne in her book Diaspora of the Gods tells us that most of these temples in Chennai were built in the last two decades by scientists and physicians. These professionals are taking temples wherever they go, thereby diasporasing the gods (the Jagannath temple on East Coast Road is an example).

What we see here is that the great temple tradition has made way for little traditions of modern swanky temples and also the street shrines; thus, urban temple construction has been democratised. This has vitalised the urban culture of the city and has established that religion, remains the core of Indian city life. And all these developments have taken place outside of the state institutional planning complex.

The New Temples

For Max Weber, the city is a community that offers a new form of association beyond religiously sanctioned social divisions (say, caste-ridden village in India). Much of contemporary theorising of the city as a space of meaning-making owe their origin to Weber. Key to the development of a modern city are the rise of the middle class, commodity culture, and global communication, which Weber believed non-Western cities could not achieve due to their foundations in familial, tribal, and sectarian identities.

Similarly, Robert Redfield saw cities as secular, heterogeneous, and disorganising, and contrasted this life with folk communities, which he thought are small, sacred, and homogeneous. Thus, the movement from the folk community to urban cultures meant a breakdown of cultural ethos. This narrow understanding led to a limited theorising of non-Western urban cultures. Unfortunately, postcolonial urban planning played into it instead of correcting the same.

Unlike the secularist belief that religion is the antagonist of modern values, the donors and champions of new temples in Chennai (as elsewhere) are not cultural dupes, nor have they been manipulated by a priestly class. They are career professionals, are world citizens, and know their science and engineering well.

It is this group that has leveraged its resources for community service and modern convenience into temple culture. No doubt these services were already available in the past, but by mainstreaming the same, they have redefined temples as spaces of modern everyday life. They not only do pujas and rituals, but also do charity, offer fellowships, arrange lectures, and do social service.

Earlier, the royal class and merchant class built temples; now the educated ones do. Today’s temples are multi-caste and multi-ethnic enterprises. The modern city dwellers want a lot more than economic opportunities and, so, cannot live with bread alone. They need God in their lives and seek the sanction of religious calendars for their plans. What it means is that the marketplace of the city needs gods and their abodes to be complete.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest