Current Affairs

Side effects of Gandhism?

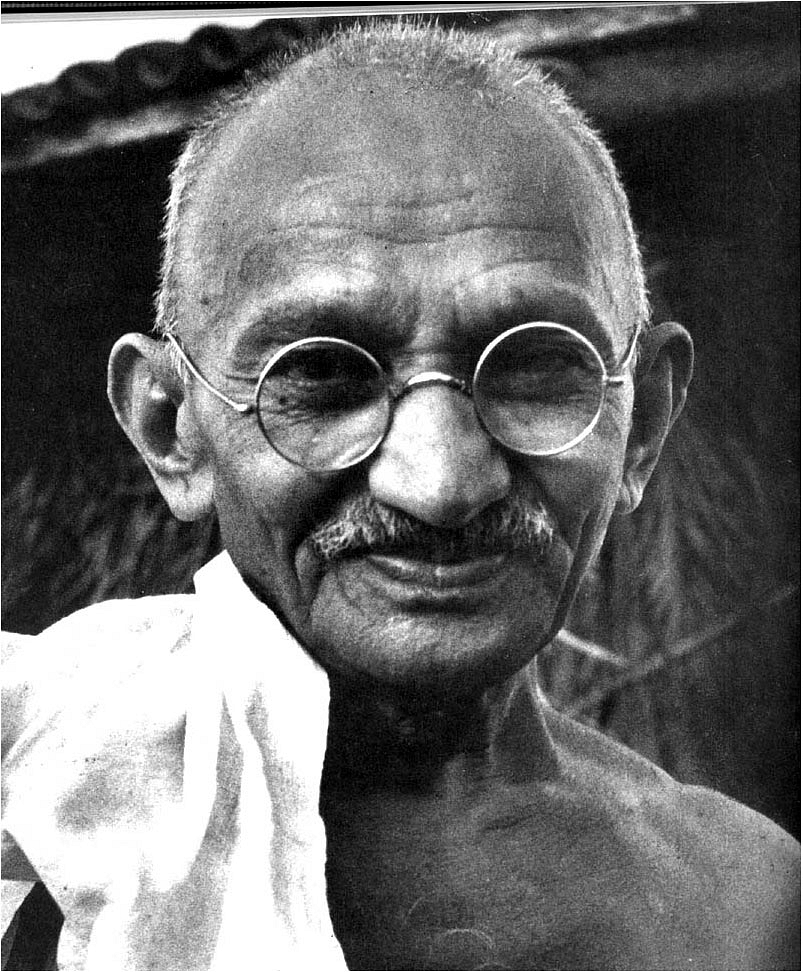

Mohandas K. Gandhi is referred to as Bapu, the Father of the Nation, in India for his enormous role in the subcontinent’s freedom struggle. A man around whom the freedom movement coalesced, Gandhi was one of the most formidable forces in the reforging of an old, forgotten nation (the political task was left to the capable hands of Vallabhbhai Patel). As much as modern India owes the lawyer-turned-satyagrahi, one must wonder if his “gift” (the revitalisation of moralpolitik) to the people of India has not had some unforeseen side effects.

Ever since its independence, India’s leaders have sought to cast themselves as the conscience of the international community. Before 1947, such a pose was quite understandable, given the premium the Indian National Congress placed on concepts such as ahimsa and satyagraha. Post-independence, however, the same mantra found few admirers among world leaders. Burdened with the responsibility of facing aggression, espionage, and insurgency as well as rebuilding the world after a devastating war, ideas not backed with resource had little applicability. As a poor country that was the recipient of international largesse, India’s leaders frequently irked Washington, London, and Moscow with their unwarranted moral pronouncements on international affairs. As Loy Henderson, US ambassador to India, 1948-1951, expressed, “India was making no contribution to the solution of world problems…and that Nehru displayed little sense of the practical realm.” Or as Josip Broz told Nehru, it was not necessary for India to have an opinion on every international matter, and India should focus on her own economy and well-being first.

As the Cold War dragged on, New Delhi’s commentary grated on everyone’s nerves. Not only did Jawaharlal Nehru and his successors frequently criticise the United States and the West, he did so in moral terms. Of course, New Delhi saw India’s own actions as beyond reproach. Indian diplomats opined on the Korean War, the French in Vietnam and then in Algeria, the Suez Crisis, the Americans in Vietnam, race tensions in the United States, nuclear tests conducted by the slowly increasing number of that elite club, and a wide assortment of other issues. New Delhi was quieter in its condemnation of the invasion of Hungary and the Prague Spring, and when Nehru did condemn the Soviet-led invasion of Hungary in 1956 (after some arm twisting by Jayaprakash Narayan), he was quickly reminded by Moscow of India’s dependency on the USSR in the United Nations (for the veto on Kashmir) as well as for arms (India’s own purchases as well as the refusal to sell to Pakistan). Even among the smaller countries, BP Koirala expressed his frustration with the Indian diplomatic corps, which he found moralising and arrogant in their dealings with lesser powers. Annoyance with India was not low in the United States either – Senator William Knowland, a powerful Californian Republican, added pointedly: “I think the time is coming when we had better start taking a realistic view of just who our friends are.” In his opinion, giving aid to India was like “giving aid and comfort to the enemy.”

Undoubtedly, part of the frustration in Foggy Bottom and Downing Street was that India adamantly refused to align itself with the West even though it was a democracy, and later, shared the West’s concerns on Chinese ambitions in Asia. Instead, India chose to sit out in the “generation’s great battle” and score cheap points by issuing vacuous moral judgement. Worse, many saw India’s position as hypocritical, always remonstrating with other states to eschew violence but not hesitating to “liberate” either Goa or Bangladesh through force. There always remained the feeling that New Delhi offered no real solutions to world problems yet extracted its 15 minutes of fame through its sanctimonious speeches. The West’s unstated response probably was close to Jim Hacker’s sentiment (Yes, Prime Minister) when he said, “Well, we can’t really defend ourselves against the Russians with a performance of ‘Henry V.'”

This tenor is not a monopoly of the foreign policy elites but is prevalent in domestic policy circles too. It is not uncommon to hear, “गरीब क्या करेंगे ? (what will the poor do?),” किसानो का हक़ छीना जा रहा है (farmers are being denied their rights),” or मजदूर को क्या मिलेगा ? (what will the factory worker get?)” in India. Over time, the focus groups may have changed, but the mentality of moral vacuousness remains vibrant. It is difficult to oppose such slogans and not appear heartless at the same time, but that was the strength of Gandhism – Gandhi realised that it would be impossible for any half-civilised society to turn down the Indian demand for freedom if couched in moral rather than confrontational terms. It is this quality, unfortunately, that is being abused by those who seek power in India – NGOs, politicians, labour unions, activists, anyone. After all, as HL Mencken reminds us, “the urge to save humanity is almost always a false front for the urge to rule.”

The purpose of this article is not to cast aspersions on Gandhi – rather, it is to damn those who are more comfortable with rote learning and uncritical parroting of ideas of which they understand little rather than positing genuine solutions, of posturing rather than proffering. Perhaps they think the citizenry is stupid, but even if that were so, should it not be part of their job to get their idea across? The problem with this suggestion is that it requires an idea worthy of getting across and a plan of action that can break it down to its logistical details – far easier to rule by moral vacuousness. It cannot be stated with certainty that such pseudo-moralpolitik arose from Gandhi’s method, but the timing is uncanny – moral rectitude as Gandhi understood it was not the language of Tatya Tope or Bal Gangadhar Tilak. And again, the fault lies not with Gandhi, who understood what he was saying and doing, but with his zombie-like followers who aped him unquestioningly. Sycophancy, rather than engagement, has become the medium of social activity, and unless this cruise control model is not challenged, political debate (or any debate) will remain the empty shell that it is. So stop; think; gather evidence. And most importantly, question – association is not a substitute for either achievement or action.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest