Economy

Demonetisation: How India Will Benefit In The Long Run

- Former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh’s government not only did not try but worsened all the problems – corruption, black money and lack of governance – considerably.

- India is still paying a price for it and will continue to pay a price for it, for quite some time to come.

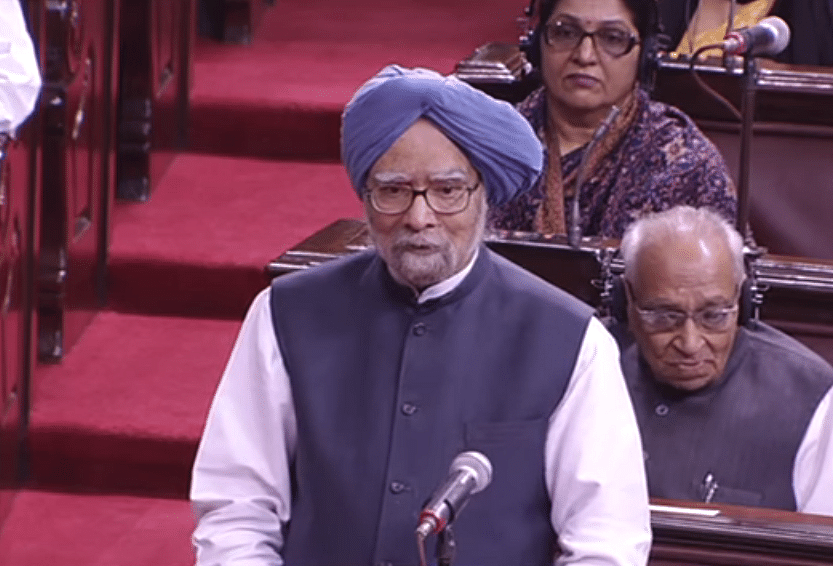

Manmohan Singh in the Rajya Sabha.

Former prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh has written a op-ed for The Hindu today. A reader of this blog brought it to my attention. I consider this op-ed a far more effective intervention than his speech in the Rajya Sabha. He has used two of my favourite expressions that I attach to economic policy-making. Or, rather the perils of policymaking: the law of unintended consequences operates and that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. I agree with both.

We can ignore his last sentence. It is theatre. We can even condemn these sentence as being grossly hypocritical:

His government not only did not try but worsened all the problems – corruption, black money and lack of governance – considerably. India is still paying a price for it and will continue to pay a price for it, for quite some time to come.

The share of high denomination notes was in ‘currency in circulation’ was 26.7 per cent in March 2001 and it jumped to 47 per cent in March 2004. By the time, UPA demitted office it had gone up to 84 per cent. In March 2016, it stood at 86.4 per cent. It was partly a response to the high inflation that the Indian economy suffered and endured under UPA and also a facilitator for storing ill-gotten wealth. So, one should dismiss the previous sentences highlighted above, with the contempt they deserve.

However, this framework of his is correct:

The ‘withdrawal of specified bank notes’ is a move that can benefit a society for a long time to come. Whether it does so or not is not possible to evaluate today nor even well into the future because, by then, the benefits may not be correctly traceable to this move which happened in November 2016. But, the costs are real, immediate and palpable.

So far, the public has been prepared to pay that price. However, it is a risk – and there is no other way to put it – that this tolerance for pain and inconvenience can fade, wane and disappear. Their assessment of the net balance of benefits and costs might shift. That is the risk that the Prime Minister Narendra Modi has taken. That risk could turn out to be a wrong one or a right one. We would not know. A risk, by definition, is one because it can result in gains or losses.

If he underestimated or misjudged the execution challenge, then the risks to him are personal (reputation, standing and image), are to his party’s election prospects and to the economy (short-term growth loss and deterioration in living standards for several (thousands or millions?).

That is why, on occasions, policymaking is entrepreneurship. Just as a gross error by an entrepreneur would be ‘punished’ by the market, a policy error would be punished by the electorate. When the market punishes the entrepreneur, the investors lose.

Of course, the big difference between commercial entrepreneurship and policy entrepreneurship is that the consequences are borne more by the society and the economy than by the policy entrepreneur. So, the care involved in exercising judgement and taking risks must be much higher. There is no way for outsiders to prove that it has not been done so. That can only be inferred in hindsight and after lapse of reasonable period.

As of now, these are still early days and too soon to conclude if events have delivered a judgement or that the developments are such that a judgement can be delivered or that it should be delivered today. No. Not yet.

This post was first published on the Gold Standard blog and has been republished here with permission.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest