Economy

GST’s Critics, Including Chidambaram, Are On The Wrong Track. The CEA Explains Why

- Why Chidambaram should read Subramanian’s interview before dashing off more critiques of GST.

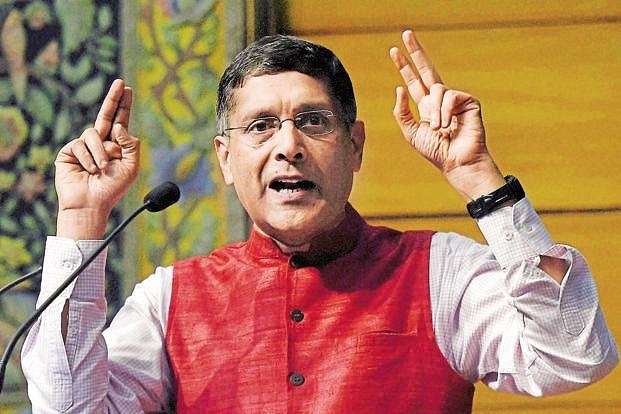

India’s Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian speaking at an event. (PTI)

The Chief Economic Adviser (CEA) to the Finance Ministry, Arvind Subramanian, has given an interesting interview to the International Monetary Fund’s quarterly publication, Finance & Development, where his answers to questions about the goods and services tax (GST) display a refreshing honesty that’s rare among professional economists.

We have been told by many economists and experts that our GST was badly designed and hastily implemented, but Subramanian explains why this was probably the only way to get it launched. What matters in the end is not a perfectly-designed scheme, but a readiness to keep correcting what needs correction. And who knows if a scheme is perfect without actually implementing it?

The interview is interesting because the CEA indirectly admits that in the real world theory rarely works as it is planned to. The GST structure, with far too many rates, has been criticised by many people, including out-of-work politicians like P Chidambaram, who rubbished the tax as very imperfect, and predicted high inflation due to its implementation.

The GST structure is now settling down (collections last month were well above last year’s average at Rs 94,000 crore), and is being constantly improved. That most experts, including Chidambaram and the Reserve Bank of India, have been proved wrong on GST’s impact on inflation is also there for all to see.

This is not to claim that the GST we have is the next best thing to sliced bread, but no one can design a perfect system in a complex economy without actually experimenting with it. What you need is agility in tweaking the scheme, not immaculate conception. The GST rates have been repeatedly tweaked and made better, and compliance is being systematically simplified.

Theory says that you need a single base rate, with some exceptions for merit goods that attract lower rates, and higher levies on non-merit goods. In short, a simple three-rate structure. But India not only has four basic rates (5, 12, 18 and 28 per cent), but also a super rate where a cess is added.

Subramanian explains why theory diverged from practice. “In principle, everyone bought into the view that it had to be simple. But… each state had its own political compulsions. One state was a producer of some good, and they would say, well, charge that at a lower rate. Unfortunately, politics required that we had to depart from this simple three-rate structure. Once it was implemented, there was a high rate, a 28 per cent slab. People realised that was leading to a lot of evasion; it was too high, and the GST Council… then started paring down the 28 per cent rate. So progress was made. There is still some way to go, and I’m hoping that over time simplicity will be achieved.”

A good GST is not necessarily a perfect one, but which keeps improving steadily.

Subramanian was asked about the impact of GST on the economy, and he gave a reply that went beyond revenues collected. He said: “there has been an almost 50 per cent increase in the number of registered GST taxpayers. We are going to see an increase in taxpayer registration, which will lead to better compliance over time. Our conservative estimate is that once it stabilises, we should get another 1 to 1.5 per cent of GDP extra revenue from the GST… Barriers to the movement of goods and services within India are going to come down. So, we also expect this huge increase in trade within India, and that’s like a kind of tariff cut in a sense. That should also add to trade and growth as well and make the Indian economy a much more attractive place to invest.”

So, GST is not only about moderate rates and higher revenues, but also the creation of a single national market for goods and services, with its own cascading benefits that may not be immediately visible.

Asked whether more work before implementation would have made the GST better, Subramanian gave a reply that should answers Chidambaram’s carping. “There is never a right moment to implement something as vast and as complicated as this. Preparation could have been better in some respects, but that’s not the way the real world and politics work. You have to seize the moment. What is important, then, is not whether you’re well prepared or not, but whether you have systems that can respond to the problems.”

Now, compare this reasonable statement with Chidambaram’s unwarranted criticism, where he called the National Democratic Alliance’s GST “very, very imperfect.... It is a mockery of the GST.” For good measure, he claimed that this is not the GST the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) envisaged.

Maybe that’s why the UPA could never implement GST. It was too concerned about perfection, when perfection was impossible to guarantee.

Chidambaram should read Subramanian’s interview before dashing off more critiques of GST.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest