Economy

How Vallabhbhai Patel Started India’s Efforts To Better Ease Of Doing Business

- When Liaquat Ali Khan tried to throttle business in India, and quoted Nehru to justify himself, it was Patel who spoke up on behalf of industries

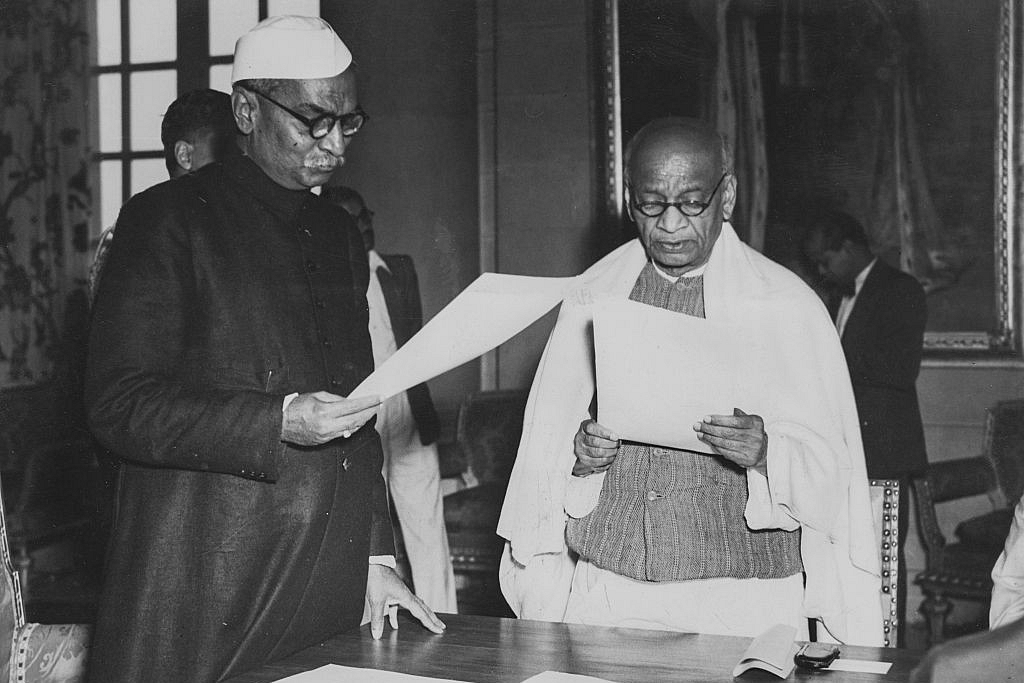

Indian President Rajendra Prasad (left) swearing in new cabinet minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel as India becomes a republic, January 30th 1950. (Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

India’s first deputy prime minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was the first top-rank political leader in independent India to understand that doing business needs to be easy for a country to prosper. This little story below is from my research for two upcoming books — The Man Who Saved India on Patel’s legacy and a yet-to-be-named history of the Indian free markets. As India celebrates a 30-rank jump in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business ratings, it might be useful to understand the economic mind of Patel.

On 7 January 1948, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the deputy prime minister of India gave a speech at a luncheon meeting. The lunch was for businessmen and organised by Badridas Goenka. Goenka was the chairman of the Imperial Bank of India from 1933 to 1955 and later became the first chairman of the State Bank of India, the largest bank in the country when it was formed in 1955.

In that speech, Patel hit out at Liaquat Ali Khan, the finance minister of the interim government of India in 1946–47 from the Muslim League party, who had presented the budget for the interim government before Indian independence on 15 August 1947.

“It is profitless to think of the past,” Patel told a roomful of worried and irritated leaders of the industry many of whom had contributed significantly in cash and kind to the national freedom movement. “Nevertheless, the world knows its history how the budget was prepared and why. The framer of the budget has now gone to Pakistan. He very well knew that it would not be for him to face the music.”

The music is what Patel was facing in that room that day. As perhaps the chief fundraiser for the Congress, and for Gandhi, since the 1920s, Patel was at the forefront of the party’s relations with industry.

He was also the prime antagonist against the Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah in partition negotiations before and after the creation of Pakistan.

But that day Patel was not only speaking against the recently departed, as a separate country, that is, Pakistan and its leaders. He was also making not so veiled barbs at one of his closest allies and rivals, Jawaharlal Nehru.

After all, what had upset the industry leaders?

The budget presented by Liaquat Ali Khan in the interim government budget of 1947–48.

That budget has one of the most troubled histories of any budget in the world. To start with, a Muslim League member was never supposed to deliver it. The government had been formed by Patel’s party, the Indian National Congress, in September 1946. The League had declined the first offer by the then Viceroy Lord Wavell to join the government. At that time relations between the Congress and the League was at an all-time low and when the League finally decided to join, it demanded a key portfolio like home, defence or finance. Wavell suggested home. But Vallabhbhai Patel was adamant that the home ministry could not be given to the Muslim League before a protracted and bitter partition of India. So the consolation prize was the finance ministry handed to Liaquat Ali Khan, Jinnah’s right-hand man, one of the founding fathers of Pakistan, and soon to be the new nation’s first prime minister.

What was in that budget?

Liaquat Ali Khan introduced a clutch of new taxes. “The most important of these was a special income tax of 25 per cent of business profits exceeding Rs 100,000 per annum.” And that was not all.

There was to be a capital gains tax, an increase in export duty on tea, and even a proposal to decrease the percentage of earnings of companies for dividend from 62 per cent to 42 per cent.

“The budget really stirred up the entire business community, both Indian and British, who were soon up in arms against Liaquat. The stock exchanges in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras were closed indefinitely in protests against the tax proposals. The big business houses and press under their control denounced the budget as a murderous one intended to destroy the economy by choking off all business activities in the country.”

As Maulana Azad writes: “Liaquat Ali framed a budget which was ostensibly based on Congress declarations, but in fact, it was a clever device for discrediting the Congress. He did this by giving a most unpractical turn to both the Congress demands. He proposed taxation measures which would have impoverished all rich men and done permanent damage to commerce and industry. Simultaneously, he brought forward a proposal for appointing a commission to inquire into allegations regarding unpaid taxes and recover them from businessmen.”

But Liaquat was a wily politician. He insisted that he was only following the principles that Congress leaders like Nehru and Maulana Azad had espoused and took inspiration directly from the criticism of such Congress leaders against the business community. In fact, he went to the extent of declaring he would have never thought of his budget proposals had it not been for the statements of Nehru.

As soon as the budget was announced, a cornered Nehru dissented and disassociated from it — including writing to the Viceroy against it.

What Patel, therefore, was doing at the luncheon speech was not just chastising Liaquat Ali Khan but also, in a sense, dissociating himself for any tinge of Nehru’s socialist economics.

Patel even went to the extent of hitting out strikes — the favourite tool of labour “agitators”. “The maximum should be produced and then distributed equitably. Instead, the labour fights before even producing the wealth.”

This is but a small glimpse of the seminal quarrels of economic thinking in India right from before it even attained its modern shape and form as a nation in 1947. As we will see through the course of this book, debates and quarrels like these defined, shaped and framed the contours of India’s tryst with the free markets.

This article was originally published on Hindol Sengupta’s blog at Medium and has been republished here with permission.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest