Economy

Quarterly ‘Hafta’ For Private Sector: Haryana’s Law For 75 Per Cent Reservations In Jobs Is Anti-India

- The new law is set to do more damage than good, especially with all the prevailing loopholes and workarounds. For the private corporations, the law amounts to corruption, red-tapism, and investment apprehensions.

- If the law stands the test of the judiciary, the private corporations must brace themselves for a quarterly ‘hafta’ in Haryana.

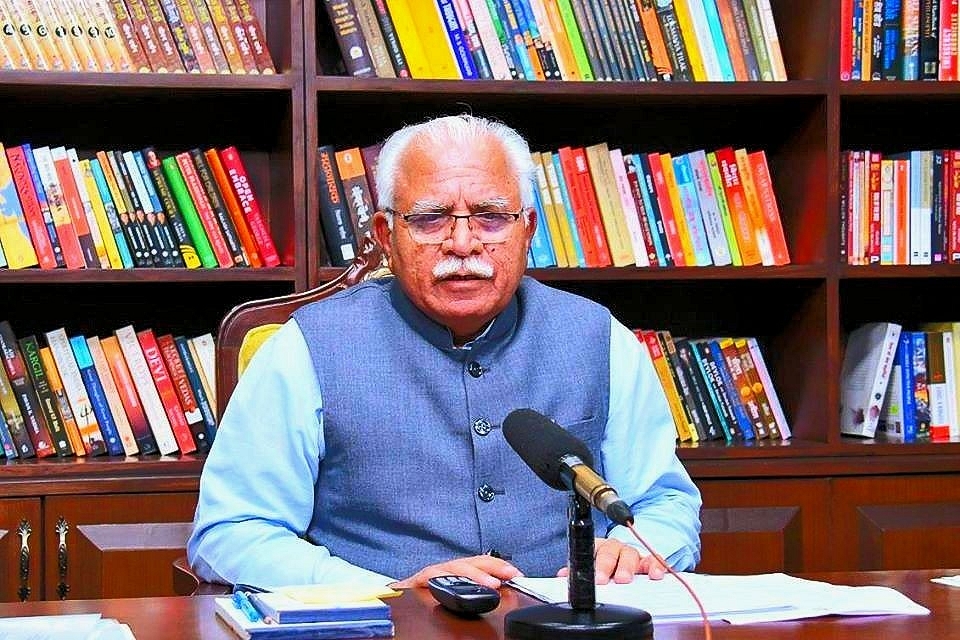

Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar. (Facebook)

As the central government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) advocates the idea of ‘one nation, one market’ for our farmers, the state government in Haryana, under the leadership of the BJP, has notified the act implementing 75 per cent reservation for people with the domicile of Haryana, not exceeding monthly salary or wages of Rs 50,000.

To begin with, the Haryana State Employment of Local Candidates Act will be implemented for 10 years from the date of commencement, will extend to all companies, societies, trusts, limited liability partnerships, partnership firms, or any person employing more than 10 people.

However, the bill will not extend to central government and state government-operated enterprises, directly or indirectly owned by either of them.

For the government, the objective behind the law was to curb the inflow of migrants that target low-paid jobs, especially those in the blue-collar professions. As per the government, the inflow of migrants has had an adverse impact on the local infrastructure, led to an increase in slums which has consequently led to environmental and health issues.

Interestingly, within the statement of object and reasons, the availability of the local workforce has been directly linked to the efficiency of the industry. Bye-bye, merit. Hello, regionalism.

From the perspective of this law, the gross domestic product (GDP) of Haryana, by sector, paints an alarming picture. For 2019-20, agriculture’s contribution to the GDP was merely 16 per cent. For industries, it was 33 per cent and dominated by the services sector with 51 per cent.

Gurugram, in the vicinity of New Delhi and as a part of the National Capital Region (NCR), is seen as the employment and development capital of the state. However, in recent years, smaller hubs have emerged in Panchkula (adjacent to Chandigarh), Karnal, Sonipat, Panipat, Faridabad and Ambala amongst others.

Thus, it would be wrong to see the law from the perspective of jobs in the agriculture or manufacturing sector alone, and for the services, the sector is not restricted to Gurugram and has a greater share in the state’s GDP. Even the upper salary cap of Rs 50,000 per month will bring a lot of workers across sectors under the purview of the law, especially the recent graduates.

Yet, the new law is set to do more damage than good, especially with all the prevailing loopholes and workarounds. For the private corporations, the law amounts to corruption, red-tapism, and investment apprehensions for the following reasons.

Firstly, the compulsory registration of employees with a gross monthly income (income before deductions) less than equal to Rs 50,000. The law gives the employer the freedom to restrict the number of employees from a certain district to 10 per cent of the total employees.

However, it is not a compulsory requirement. Employees availing of the reservation will have to register themselves on a designated portal.

The companies will also be required to furnish a quarterly report detailing the number of local candidates employed for the quarter on a designated portal.

The compulsory registration, quarterly reporting, and gross income open up opportunities for dummy hiring.

For instance, what if, for the sake of registration, companies hire gig workers with salaries as little as Rs 5,000 per month or on a contractual basis where wages are paid for the work done? Thus, can a company get workers merely to fill the numbers while hiring them for a job that requires them to show up for one day in a month?

Two, the exemption clause. The government shall have a designated officer not below the rank or equivalent to that of a deputy commissioner. For claiming an exemption from the law, the employers can appeal to this designated officer in a manner prescribed by the government, citing the lack of desired skill, qualification, or proficiency amongst the available candidates.

For a private company, of any size, to have their recruitment process validated by a government officer violates all the ethos of ‘ease of doing business’. As per the law, the designated officer can either accept the appeal of the employer, reject the claim, or worse, direct the employer to train local candidates to achieve the desired skill and qualification.

Thus, the law wants the designated officer to double up as human resources or education consultant for independent tax-paying private companies in Haryana.

For the company, the obvious workaround is to keep the bar of the skill required high enough to have its claim to the designated officer accepted.

For instance, can a service company keep proficiency in a foreign language, a skill that might be required once a year to interact with a foreign client, as criteria for the job? What if companies start overstating criteria? What happens to jobs that require technical or academic qualifications or skills achieved with elaborate training? Will universities be forced to ignore better talent from Delhi if they are operating in Gurugram or any other city?

Three, the appalling powers of the designated officer. The law allows for an authorised officer, an officer of the state government not below the rank or equivalence of the sub-divisional officer, to examine the quarterly reports furnished by the companies on the number of local employees.

The authorised officer has been given the powers to call for any record, information, or document in possession of the employer for the purposes of verifying the information furnished in the quarterly report. Thus, the authorised officer can call for any internal company records pertaining to employees. So much for not making villains out of entrepreneurs.

The authorised officer has also been given the power to enter any premises of the company, at any time between 0600 hours and 1800 hours with a single day notice to carry out the functions listed in the act, defying the independence of the private corporation.

The officer can also enter the premises to determine if the functions of the law are being complied with. The officer will also have the right to examine ‘any’ record, register, document if they have a reason to believe that an offence under this act is being committed.

Thus, from quarterly reports to extempore inspection, the law expands red-tapism in the business and could lead to bribing of authorised and designated officers. Think of it as a ‘quarterly hafta’ imposed on the private companies operating in Haryana, not by virtue of money necessarily, but enforcement of human resources policies.

Any authorised or designated officer can use the provisions to harass any private individual, group, company, or corporation. So much for ease of doing business.

The law also has scope for a general penalty and the provision for the employer to appeal to an appellate authority (an officer of the government not below the rank or equivalence of the Labour Commissioner) to appeal against the order of a designated officer.

Interestingly, the government has also inserted a backdoor exit for itself to tackle any embarrassment that may follow the implementation of this law.

As per a provision, if there is any difficulty in giving effect to the provisions of this act, the government, within a period of two years of the commencement of the act, make such provisions not inconsistent with the provisions of this act to remove the difficulties that hinder the implementation of this law.

Thus, tomorrow, the government can list certain sectors or industries where the law may not apply, may require reservation less than 75 per cent, or any other provision that makes for better and easy application of the law.

Irrespective of what it may do to the state, its local employment growth, or its environment, the law sets a bad precedent. By endorsing a law like this, the BJP government in Haryana, and consequently the BJP government at the Centre, are allowing for the creation of sovereigns within the Indian state when it comes to private sector employment.

Already, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Telangana have flirted with the same idea, and now that precedent has been set by the biggest political party of India, the regional parties governing several states would want to follow the BJP to secure the local vote bank. There’s no silver lining here, only a disaster in the making.

A point must also be made about the political compulsions that may have led to this, given the Jannayak Janata Party (JJP) with 10 MLAs in an assembly of 90, and critical to the coalition government of the BJP, had this as a poll promise.

Pulling the plug on the law would have had a destabilising effect on the government in Haryana, a peril the Centre would not want to risk with the ongoing farmers’ protests.

Yet, the law, with its workarounds and loopholes, only creates an atmosphere of investment apprehension, red-tapism, harassment of private corporations, and blatant corruption.

The law goes against everything the BJP has stood for at the Centre in the last six years, from national integration to GST (goods and services tax) to farm laws. It’s bad optics, bad policymaking, bad politics, and bad precedent. It is anti-India.

If the law stands the test of the judiciary, the private corporations must brace themselves for a quarterly ‘hafta’ in Haryana.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest