Economy

Why Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari Is Right In Admonishing Cement Companies For Increasing Prices

- Why Union minister Nitin Gadkari is unhappy over the unjustified increase in cement prices, which is hurting the country’s infrastructure development initiatives.

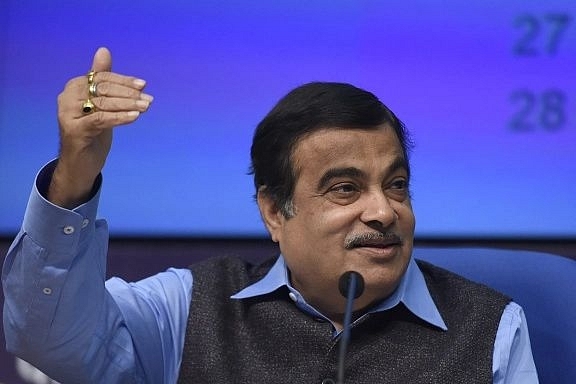

Union minister Nitin Gadkari at a press conference in New Delhi. (Sonu Mehta/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

Nitin Gadkari, Union Minister for Transport and Medium, Small and Micro Enterprises, on 4 June (Tuesday) criticised cement manufacturing companies for raising prices without any justification. The minister had in the past one year charged the cement companies with cartelisation a couple of times.

In July last year, the Narendra Modi government had threatened to impose price controls on cement. Gadkari, in particular, holds the cement companies responsible for being a hurdle in constructing more cement roads in the country.

Accusing the cement manufacturers of forming a cartel, the Union minister said the price increase by the firms was unjustified when the input costs have not increased.

In Chennai, except two companies — Parasakti and Penna — cement firms charge upward of Rs 350 for a 50-kg bag of portland pozzolana cement, while ordinary portland cement ruled between Rs 370 and Rs 400 a bag. The manufacturers hiked prices in February and March this year.

Announcing its results for the January-March quarter this year, Chennai-based India Cements said that selling price in the quarter had gone up 6 per cent compared with last year. This has led to the Builders Association of India, which had won a case against the Cement Manufacturers Association and its members for forming a cartel, demanding the setting up of a regulatory authority to check prices.

In March this year, cement production increased to a record 33.12 million tonnes (mt) before dropping in April to 28.73 mt, according to Trading Economics website. Cement production in the first half of last fiscal increased 14.4 per cent to 163 mt.

However, one problem with the cement industry is the capacity utilisation. In 2018, cumulative cement production capacity in the country, the world’s second biggest producer, was 502 mt.

The housing and realty sector consume 65 per cent of the country’s total production, while public infrastructure offtake is 20 per cent, with industrial development making up the rest. But only 65-70 per cent of the capacity is being utilised, though it was 71 per cent last year.

The cement industry is freight intensive and hence transportation is uneconomical. This has led to cement manufacturing being region specific with the highest capacity of 32 per cent being installed in the south.

According to an analysis released by Ambuja Cements management in October 2018, input costs rose 11 per cent last year compared with 2017. Landed cost of slag, an important component, increased 55 per cent but the cost of fly ash dropped 4 per cent.

Use of cheaper activated gypsum and procurement from competitive sources help cut gypsum prices by 5 per cent, the company said, adding that it took up various other measures to improve its manufacturing efficiency.

The January-March quarter this year has seen corporate India performing below par. Companies in only cement and sugar sectors made good profits.

The Economic Times reported that fuel prices declined for cement companies and the sector would gain from Modi government’s thrust on road construction and low-cost housing. The financial daily also said revenue growth was likely to be good for cement companies in northern, southern, central and eastern parts of the country.

Despite these, there is some justification in Gadkari’s outburst against the cement companies. One, public infrastructure consumes 20 per cent of the cement produced in the country. Two, cement companies have been breathing easy after the Modi government raised customs duty to 200 per cent for imports from Pakistan following a terrorist attack on a Central Reserve Police Force convoy at Pulawama in Kashmir. The cement segment gained from this since the higher duty put a stop to consignments, which attracted 7.5 per cent duty until then, coming from the neighbouring country. Would cement companies have raised the prices had imports from Pakistan continued?

The third reason why Gadkari seems to be justified in his anguish against the hike is the ruling by the Competition Commission of India (CCI) against the Cement Manufacturers Association and 11 cement firms in 2016. The case was filed in 2010 and the CCI ruling in August last year saw the cement companies being penalised to the tune of Rs 6,300 crore. The cement companies got a stay from the Supreme Court in October, where they have appealed against the CCI judgement.

The findings of the CCI, based on the Builders Association of India complaint, are interesting. The CCI had asked its director general (DG) to submit a report on the builders’ plea. The DG said that two group of companies had a pan-India presence, controlling 40 per cent of the market share, while a few producers enjoyed strong presence in one or two regions of the country enjoying a 50 per cent market share.

The DG’s probe primarily focussed on 21 cement companies that enjoyed a 75 per cent market share in the country and the industry was oligopolistic in nature. The DG also found that no company had the power to operate independently in the market and this has helped the companies to enjoy an over 25 per cent profit operating margin.

An interesting finding by the DG was that cement prices rose faster than input prices. Within a span of six years between 2004-2005 and 2010-11 cement prices doubled to Rs 300 a bag. The probe also found that there were frequent changes in cement prices — sometimes twice a week during the period.

Though the investigating official was told that cement price hike was based on market feedback, there was no formal or systematic mechanism or documentation to justify the cement producers’ decision to hike prices. The DG also pointed to a 2010 report by the Tariff Commission saying cement prices were unreasonably high and there was scope for correction.

The probe found that prices of cement of various companies moved in the same pattern and direction and close to each other. The DG found that cement production capacity increased from 157 mt in 2005-2006 to 287 mt by 2010-11 but capacity utilisation dropped to 73 per cent. The cement companies failed to give a convincing reply for the drop in capacity utilisation. The probe hinted that cement firms under utilised their capacity to raise prices and thereby earn “abnormal profits”.

Finding that cement despatches by the manufacturers were identical, the DG said decision to increase or cut despatches indicated “some kind of meeting of mind” or in short cartelisation. Another curious aspect the probe found was that while capacity utilisation dropped, the price index increased. This, the DG, said was a deliberate attempt to cut supply and raise prices.

The investigation revealed the 20-50 per cent hike in cement prices during the last quarter of 2010-11 fiscal over the third quarter was mainly due to supply control by reducing capacity utilisation.

With cement demand being inelastic, any cut in prices wouldn’t increase sales and would only cut profit margins. Hence, there was collusion by the cement firms in controlling supply and they used the media to signal hike in prices.

Though ACC Limited and Ambuja Cements had come out of the Cement Manufacturers Association, the companies kept in touch with the association and took part in its meeting. Cement prices were hiked after such meetings. The DG said the manufacturers’ association provided a platform for cartelisation.

The manufacturers’ association denied any cartelisation and dismissed the DG’s charges as vague and contended that no materials had been placed on record and witnesses were not questioned during the probe. Various cement companies, too, denied cartelisation.

The CCI went into the detailed report of the DG and heard the responses of the cement companies. The commission said it had no hesitation in holding the view that the cement companies were interacting with each other. The cement manufacturers’ association was used as an anti-competition platform, the CCI said and added that it had found economic evidence, too, to support its view.

There seems to be little change in the situation despite the CCI findings. The Centre would do well to ask the Supreme Court to dispose of the cement companies petition quickly, while it should mull setting up a pricing authority on the lines of National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority.

Such initiatives will help the government in completing its projects with minimal cost overruns in sectors such as infrastructure and social welfare, in which houses and toilets are being constructed to benefit the economically weaker sections.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest