Ideas

How To Reform Civil Services Recruitment – A Radical Approach

- Piecemeal changes in the recruitment process will serve no purpose. Here are a few radical changes that can be undertaken.

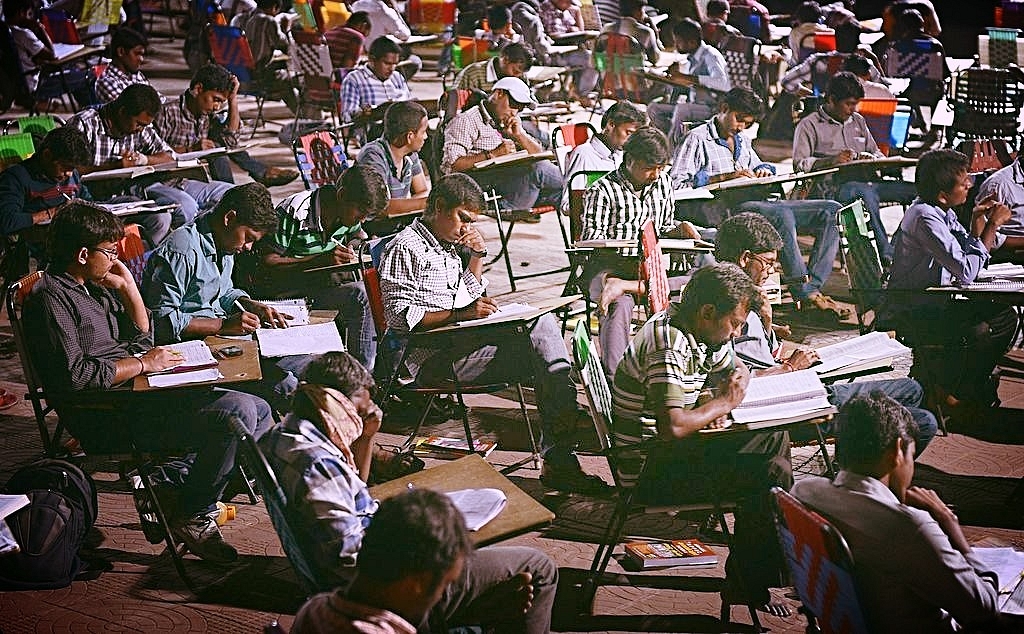

Indian students preparing for an examination (NOAH SEELAM/AFP/Getty Images)

The civil services are seen as the backbone of governance for the Indian state. Over time, and with changes in technology, economy and society, the quality requirements for selection of civil servants have changed. The Government of India and Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) understand these new requirements. They have undertaken steps to recruit the best from the available talent pool and train them to meet the equilibrium of efficient governance and understand the needs of the citizenry.

Recently, the Shri B S Baswan Committee report has been in the news. It seeks to recommend changes in the recruitment pattern to match the needs of today. The report and its recommendations are yet to be made public.

Civil services recruitment in India needs radical reforms. The piecemeal approach of tweaking subject papers, both in the preliminary and main rounds or changing the age and subject requirements will not cut it. My key recommendation is to change the eligibility criterion for aspirants, from holding an undergraduate degree to being a high-school graduate.

Other recommendations and the reasons thereof are as discussed.

Changing the eligibility criteria

There is no direct link between a graduate’s area of study and the civil services. Higher education in India, with some exceptions, is not up to the mark. So, a student spending three to five years of their time on a bachelor’s degree isn’t necessarily making the most fruitful use of time, energy and resources as far as the civil services are concerned. On the other hand, recruitment directly after Class 12 would allow the government and the UPSC to train recruits for a period of three to five years (depending on the service), as per the needs of the administration.

As per the 2015-16 report of the Human Resource and Development Ministry, the gross enrolment ratio (GER) in higher education in India is a meagre 24.5 per cent. For scheduled castes, it is 19.9 per cent and the figure is even lower for scheduled tribes, at 14.2 per cent. Thus, recruitment after class 12 would promote inclusiveness in governance structures and social equity. Further, it would boost gender parity, which is minimum at the level of higher education.

At the undergraduate level, 40 per cent of our students are enrolled in the arts/humanities/social sciences stream. Then comes science, at 16 per cent, engineering and technology at 15.6 per cent and commerce at 14.1 per cent. The highest number of students is enrolled in the Bachelor of Arts programme, after which come the Bachelor of Science and the Bachelor of Commerce programmes. Only 5.55 per cent of the recognised programmes account for 83 per cent of the total students enrolled in higher education. In our country, where even engineering and management education is at the lowest stratum, arts and sciences are treated as akin to untouchables of the past. With the maximum students enrolled under such programmes, what kind of governance-specific or even personality level would be developed is hard to say. Also, 50-60 per cent of civil services recruits come from either an engineering or medical background.

It can be concluded that changing the eligibility criterion to class 12 graduate would increase the recruitment base and thus promote equity and merit. Anyhow, the recruitment is done through rejection, which can be done at any stage. So, why not at an earlier stage, when time and resources can be utilised productively?

Changing the age criterion

With the change in eligibility criterion, the logical age qualification would then become 17-21 years of age, for the general category. The government recognises a person to complete their class 12 by 18 years of age. A one-year margin on either side shall be provided to the students to accommodate brilliance or a late start. A maximum of two immediate attempts, like the joint entrance examination (JEE), shall be provided to the general category, three to the non-creamy layer of other backward castes (OBC) and four to the scheduled castes and five to the scheduled tribes (though the two- and three-attempt rule is recommended for unreserved, OBCs and others respectively).

The advantages of such a step are manifold. First, a young recruit is more susceptible to training and can respond positively. Second, political neutrality, the very essence of the civil services, can be instilled. As one grows with age, it is very difficult to maintain political neutrality after having been in the thick of it for long. Third, those who fail to get selected for the civil services would not, unlike today, waste their productive years in giving the examination year after year, with the dedication and hope of working for the government. Fourth, the students in undergraduate studies and, most importantly, in postgraduate and research studies would not neglect their course and research to gain selection in the civil services.

It is not a hidden fact that many students take admission to postgraduate and research courses not to pursue specialisation or to undertake research, but because it is the easiest medium to continue to prepare for the civil services examinations. The teachers and research guides are lenient enough in our universities to help a student achieve their dream of becoming a civil service officer (not civil servant) but at the expense of research and education.

It can be concluded that this would not only provide a group which can be well-trained but is also politically neutral and open-minded. It will also help students in streamlining their career choice at an early age and will avoid the capture of seats in colleges just to prepare for the civil services. Thus, it will not only lead to a larger pool of good bureaucrats, but also good engineers, doctors, teachers, researchers, scientists and social scientists, among other professionals.

Changing the training module, pattern and duration

I recommend that the training duration for Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Police Service (IPS) and Indian Foreign Service (IFS) be five years, which, in case of other civil services, may be three to five years. In this manner, they may be conferred with a bachelor’s degree in case of a three-year module and an integrated master’s degree in case of the five-year module.

The training programme may be prepared depending on the requirements of a generalist service in this information technology age. It may be incorporated by getting the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), Indian Institute of Science, Education and Research (IISER), Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), among others, on board. It would work in the direction of incorporating history, diplomacy, economics, management, science, engineering, management, agriculture, urban development, ethics, philosophy, culture and other subject-specific requirements of the services. It will help in creating efficient and modern generalist officers, which is the need of the hour. Moreover, service-specific training immersion programmes may be designed at the end of each semester or trimester.

It can be concluded that this would be in the direction of creating a comprehensive training programme incorporating both theory and practical modules, helping produce efficient and vibrant officers. Such training is far more efficient than the three-, four-, five-year university programme, which is redundant when seen in the light of the poor higher education environment in India. Thus, the citizenry would be served by young, dedicated, vibrant and experienced professionals.

Designing the examination calendar

The civil services (preliminary) examination may be conducted online in December and the marks declared almost immediately like in the case of BITSAT and GRE. In a democratic country, such an approach is highly recommended. Moreover, in case of failure, the student will have the time to re-focus on other examinations that may be conducted later in the year.

The civil services (mains) examination may be conducted in April, just after the board exams.

The civil services personality development test (interview) may be conducted in June-July and the results declared in the same month.

The pattern of the examination and the syllabus shall definitely be different from the current pattern. But its discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

When to undertake such a reform?

The minimum time-gap between notification and execution of the reform shall not be less than four years. It will serve two purposes. First, the people already preparing for the examination would not be at a disadvantage. Second, the people who will take the test under the new format must have enough time to introspect, decide and prepare. To illustrate, if the Union Public Service Commission notifies such a change in the pattern in January 2018, then a change in the examination pattern must not be made before December 2022 (if this calendar is followed).

Summing up

Piecemeal changes in the recruitment process will not work. Radical changes in the eligibility criteria of education and age are necessary. A comprehensive training programme serves a better purpose than a redundant university degree in knowledge creation, professional experience and personality development. Such an approach would further enable millions of youth in the country to utilise their quality productive years more efficiently and in a planned and organised manner. Moreover, the students in colleges would focus on specialisation, research and development. Overall, it would take the nation forward on the path of inclusivity, equity, good governance, research and development.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest