Ideas

Time For A New Generation Of Scholars To Study Savarkar

- Current debates about Savarkar are often based on flimsy grounds, and he is caricatured by both the left and right for partisan reasons.

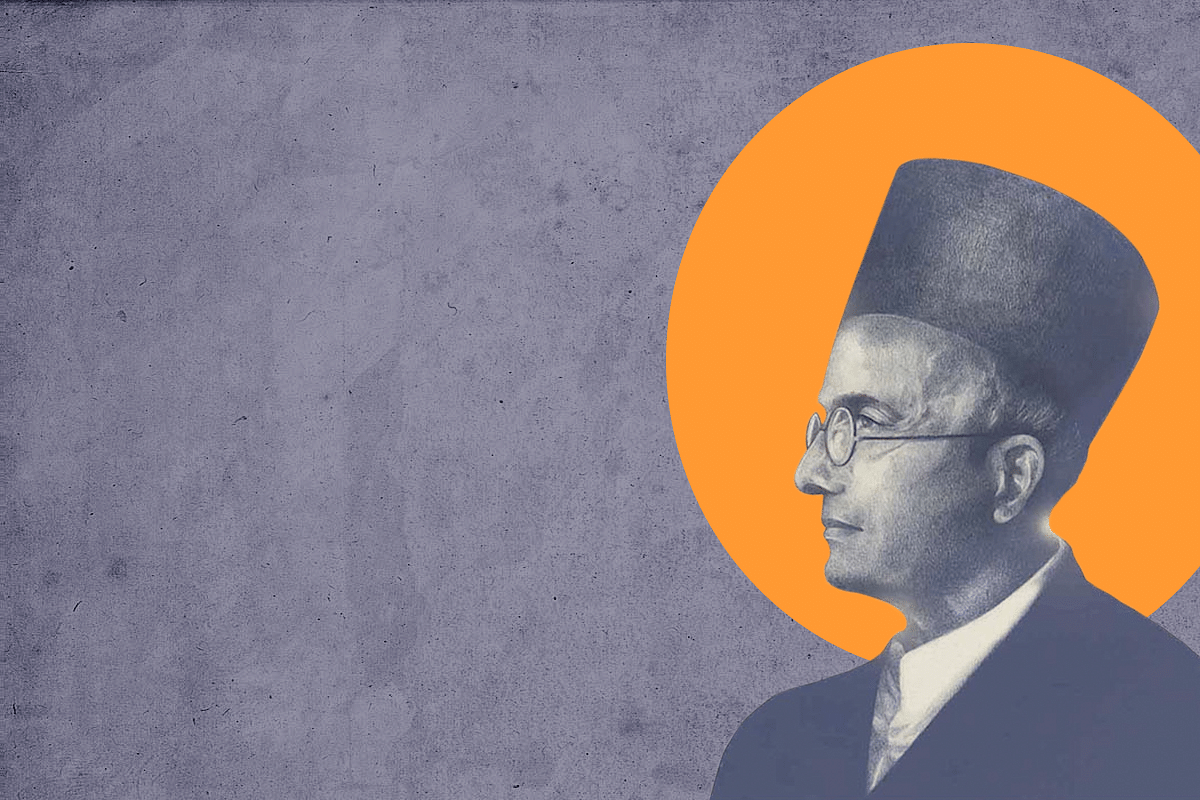

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was freed from internal exile in May 1937. Twenty-seven long years had passed since he had been illegally arrested by the British police on French soil in March 1910. These years out in the cold included a decade of intense suffering in the brutal Cellular Jail in the Andamans. Savarkar was then shifted to Ratnagiri on the condition that he would not take part in any political activity. His final release was widely welcomed. There was a lot of interest about his next move. Two young socialist leaders, S. M. Joshi and Achyut Patwardhan, who would later become heroes of the 1942 underground movement, even went to Ratnagiri to persuade Savarkar to join the Congress Socialist Party.

Savarkar reached Mumbai a few days after he became a free man. The public meeting organised in his honour was led by an eclectic group of leaders from the city. There was Jamnadas Mehta, a follower of Lokmanya Tilak, a member of the Democratic Swaraj Party, and the man who had led the campaign to free Savarkar. There was Comrade M. N. Roy, who had once worked with Lenin in Moscow, and had emerged a few months earlier from his own incarceration. There was Senapati Bapat, who was a member of the revolutionary group founded by Savarkar in London, and who had by then moved into the Gandhian camp, as had the late V. V. S. Aiyar, another old comrade from the India House days. There was Khurshed F. Nariman, the lawyer who was recently the Congress mayor of Bombay, and a steadfast admirer of Savarkar. There was Lalji Pendse, the Marxist intellectual and independent trade union leader.

This was a generation whose lives had been electrified by the example set by Savarkar in his early years. In his speech that day, Savarkar assured his admirers that he would be with them in the struggle for Indian independence. He then said he agreed with the socialists that people should be freed from the clutches of religion; what he disagreed with was the attempt to undermine the rights of one religious community to satisfy another religious community. He told the audience that his final goal was a united Indian nation where each citizen had equal civil and political rights. Savarkar also said that his struggle against untouchability was a complement to the wider socialist struggle, and that the Left should realise that oppression is not always just an economic issue. He then gave the examples of B. R. Ambedkar and N. S. Kajrolkar, who had to deal with untouchability despite not being poor. These broad themes — of protecting Hindu interests, building a modern nation state and fighting caste oppression — would continue to feature in his speeches after he plunged back into national politics as president of the Hindu Mahasabha.

There is one charming episode from around this time that throws more light on the admiration that even political rivals had for Savarkar. In his autobiography, the film maker J. B. H. Wadia has recounted how M. N. Roy, who usually preferred Western clothes, once arrived at the breakfast table in the Wadia home dressed in a white dhoti-kurta. Roy explained to his puzzled host: “I am going to pay my respects to Veer Savarkar and I thought I should do it in the fittest manner possible. I am sure the old man will be pleased to see me dressed as a full-fledged Indian rather than as a Westernized revolutionary.”

Such a warm reception for Savarkar from across the political spectrum seems almost unbelievable today. He is now an enigma to most people. It is unfortunate that not enough is known about Savarkar, despite all the noise surrounding his name — “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”. One important reason is that most of his own writing is in his native Marathi. The few who have dipped into the Savarkar literature have restricted themselves to Essentials of Hindutva, arguably one of his weakest works, though also the most influential.

The other reason for the veil of ignorance is that both his supporters as well as detractors have preferred to cherry pick what suits their political agendas. The former prefer to remember Savarkar for his astonishing escape bid at Marseilles harbour or the harrowing punishments he had to face in the Cellular Jail or his intense dislike for the Muslim politics of his day. The latter prefer to focus on his mercy pleas to the colonial government or his possible involvement in the Gandhi murder conspiracy.

The man who even his political rivals once respected has thus been lost in a fog of either hagiography or demonisation. Savarkar deserves better. He was a Hindu nationalist who attracted the ire of religious conservatives for his merciless attacks on social traditions; he was a Mazzini liberal who had a fascination for military power; he wrote about the historical divide between the two main religious communities, agreeing with Jinnah that these were two nations, but hoped to unite them under a common democratic Hindustani nation state; he took a hard line against the Muslim politics of his day but had read the Quran as well as tried his hand at writing Urdu poetry; he was an avid student of history who believed that India has to move forward into the age of science rather than seek inspiration from religious texts. This essay tries to provide some vignettes of Savarkar that will hopefully lead to more rational debate about him as a public figure.

Sceptics may reasonably wonder whether the widespread admiration for Savarkar recounted earlier came when there was a high tide of public sympathy just after his release, and that the tide later receded. That is not so. One of the political groups that Savarkar collaborated with in the years before independence were the Indian liberals led by Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru. He was invited to some of their meetings well after the initial euphoria following his release had petered out. The philosopher of armed revolution actually worked in tandem with the constitutionalists for some time.

In one of the annual conferences of the Indian Liberal Federation, the veteran liberal V. S. Srinivasa Sastri gave an interesting insight into Savarkar: “I wish to say a word about Mr. Savarkar personally … I had expected to see a gentleman perverse and obstinate and loud. But what did I find? I found a somewhat thin-looking, quiet Maharashtra chap, speaking slowly and deliberately, seldom raising his voice, but always apparently in full possession of his mind and knowing exactly what he wanted. I was still more surprised that in his talk all that day there was nothing to remind me of his unparalleled experiences. Those who know anything about Mr. Savarkar know that his life has been marked by the greatest hardships and a considerable amount of what he would think was undeserved persecution. He was for many days in absolute danger of his life and passed through concealment and flight several times over before he found safety. Even after all this I was, as I said, agreeably surprised to find no note of bitterness in his speech, nothing certainly anti-Government, nothing anti-British. I at once conceived a great admiration of the man …”

This was followed by another mention in a speech by R. P. Paranjape, the brilliant mathematician who was the principal of Ferguson College in Pune when Savarkar had to face disciplinary action as a student for his political activity: “People know a great deal about Mr. Savarkar and Mr. Sastri has spoken to you his impressions of him. My own acquaintance with Mr. Savarkar goes a long way, about forty years back, when he was a student under me in College, while I was a Principal. I had occasion then to take certain disciplinary steps against him, and to a certain extent I claim to know something of the life of Mr. Savarkar. All the same on this occasion he has behaved as a real self-respecting and patriotic person should. One should not judge of Mr. Savarkar from simple newspaper reports. He bears me no grudge and I bear him no grudge for anything that happened in his life some forty years ago. As a matter of fact, when about a few years ago I first saw him after his release, he felt as a pupil meeting his old Guru. And in recent times his attitude on various public questions has been such as every liberal here can almost fully endorse.”

Here were the true disciples of Gopal Krishna Gokhale heaping praise on Savarkar. It is interesting that he too had similar affection for their master. Savarkar was from the Tilak school of politics, and yet he recounted in his book on his years in the Andamans how he broke down when he was told that the Gokhale, the main rival to Tilak in the Congress, had died. His surprised jailor asked Savarkar why he was crying at the death of an enemy. “We had differences but we were not enemies. He was one of the best products of our age, and an undaunted patriot and a sincere servant of India,” Savarkar replied. Savarkar would tell his followers in the revolutionary camp that they should aspire to match the deep learning of moderates such as Gokhale and R. C. Dutt.

Savarkar continued to have admirers from different political persuasions even after he was acquitted in the Gandhi murder trial, a far cry from his political untouchability today. In May 1952, Savarkar was in Pune to dissolve Abhinav Bharat, the revolutionary society he had set up many decades ago to fight for Indian freedom. In his speech on the occasion, which remains relevant even today, Savarkar explained that revolutionary organisations such as Abhinav Bharat have no place in a constitutional republic, and that anarchy would otherwise be a threat to national stability. He added that opposition parties — be they in the Hindutva or communist camps — should respect the fact that the Indian people have handed the task of running the government of free India to the Congress party. It was the duty of all citizens to support the elected national government, even as they had the right to criticise it.

Among the people on the stage with Savarkar that day were Senapati Bapat, Keshavrao Jedhe of the Peasants and Workers Party, and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh chief M. S. Golwalkar. A few years later, in May 1958, Savarkar was felicitated by the Greater Bombay Municipal Corporation to mark his seventy-fifth birthday. The felicitation was chaired by the mayor of Bombay, Comrade S. S. Mirajkar of the Communist Party of India, an unthinkable event today. A few years earlier, Asaf Ali had described his old India House comrade Savarkar as someone who lived in the spirit of Mazzini and Shivaji, which was apt considering the fact that the Italian revolutionary and the great Maratha king were his political heroes.

Savarkar died in 26 February 1966. His body was burnt in the electric crematorium in Mumbai because the atheist did not want any religious rites performed. Among those who paid their last respects to the departed revolutionary were several distinguished Mumbai citizens, including Comrade S. A. Dange. The Marathi magazine Satyakatha, the voice of the literary establishment of the day, had a special section on Savarkar in its May 1966 issue. Marathi writers of the stature of V. V. Shirwadkar “Kusumagraj” — who was later to win the Jnanpith Award in 1987 — paid tributes to him in that issue. The great Marathi poet described Savarkar as a modern Prometheus, who stole fire from the Gods to bring light to humanity, and who was made to suffer for his selfless act. The historian Y. D. Phadke wrote a more critical piece on Savarkar in the same issue. Meanwhile, Acharya P. K. Atre wrote 14 special editorials on Savarkar in his newspaper over the next fortnight. Two days after Savarkar died, Comrade Hiren Mukherjee of the Communist Party of India stood up in the Lok Sabha to demand that parliament pay homage to Savarkar. Dange described him there as a great anti-imperialist revolutionary while Indira Gandhi said Savarkar was a byword in daring and patriotism.

The point of repeating all these examples is to show that Savarkar had admirers from all walks of life till the very end of his life. At the same time, as in the case of his reaction to the death of Gokhale, Savarkar too could offer personal support to the very rivals whom he bitterly lashed out against in political battles, in a sense reciprocating what he experienced from those who often opposed him politically. For example, in 1940, he issued a statement after Jawaharlal Nehru was sentenced to four years in jail. “The news of the sentence of four years imprisonment passed on Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru must have come as a painful shock to every Indian patriot. Inspite of differences as to principles and policy which compel both of us to work under different colours, I shall be failing in my duty as a Hindu Sabhite if I do not express my deep appreciation of the patriotic and even the humanitarian motives which had actuated Pandit Jawaharlalji throughout his public career and my sympathy for the sufferings which he has consequently had to face.”

In 1943, Savarkar was part of the All-Party Conference led by the Allahabad liberal Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru when he publicly called upon Gandhi to end his fast because it was important “to leave no stone unturned to save his precious life”. Savarkar was also among several leaders such as B. R. Ambedkar, M. N. Roy and Rajaji who stayed away from the 1942 Quit India movement. Each had his own reason. Savarkar had called on Hindu youth to join the army to acquire military skills. His reason was that nationalists should build their capabilities to prepare for the freedom that was inevitable at the end of the war, and that getting stuck in jail was a strategic error.

Yet, when the Congress leadership was arrested in August 1942, he spoke out for them. “The inevitable has happened; the foremost and patriotic leaders of the Congress Party, including Mr Gandhi, are arrested and imprisoned; the personal sympathies of the Hindu Mahasabhites, and Hindus in general, go with them in their suffering for a patriotic cause,” Savarkar said in a statement, though he also reiterated that his party would not support the Quit India resolution. He later lashed out at party workers who heckled Gandhi during a prayer meeting in New Delhi days before the assassination, calling their act undemocratic. In a public meeting in Pune, when Savarkar was heckled by young socialist students, he scolded them by saying that decency demands that they hear him out just as he would listen to them.

Savarkar was a political realist. The Hindu Mahasabha had vehemently opposed the partition of India in August 1947, but it was quick to extend support to the new national government, at a time when the socialists and communists had misread the transfer of power as a case of false freedom. The socialists had boycotted the celebrations while the communists were preparing for armed rebellion. In his biography of Savarkar, Dhananjay Keer noted that Savarkar encouraged Shyama Prasad Mukherjee to take up the offer to join the first government headed by Jawaharlal Nehru. Savarkar had petitioned the Constituent Assembly that the official flag of the new nation state should be the saffron one, but he hoisted the tricolour outside his Mumbai home on 15 August 1947, since that had been decided by the government of free India. He would later welcome the Constitution as well, and especially its abolition of untouchability.

Savarkar was an early supporter of the moving spirit of that constitution, B. R. Ambedkar. In her pioneering Ambedkar biography, the American scholar Elinor Zelliot writes that Savarkar backed the Dalit march led by Ambedkar in 1927 for access to the public tank in the town of Mahad, south of Mumbai. “Support for the satyagraha came from a number of sources, among them Veer Savarkar, the revolutionary whose interest in the Depressed Classes may have stemmed from his desire for a stronger Hinduism, but whose support nevertheless was bold and unorthodox,” she wrote.

This was at a time when Savarkar had focussed a lot of his energy on social reforms, and some of his provocative essays in Marathi magazines such as Kirloskar will shock even contemporary social conservatives. In one essay, on how two phrases define two cultures, he compared the Indian quest to seek solace in the past while the European nations prided themselves for their up-to-date knowledge of the world, from new technology to the cut of a suit.

He wrote in a Marathi essay, as translated by Mint newspaper: “So, reformers who rock the boat, who become unpopular, who disturb the social balance, who hurt religious sentiments, who turn their back on majority opinion, who think rationally—all these reformers face the inevitable consequences of their actions. Every reformer has had to face these challenges. This is because social reform—by definition rooting out any evil social custom—means taking on the persistent social beliefs of the majority.” The three reformers he specifically mentioned in his essay were Buddha, Jesus and Mohammad.

Savarkar would later invite Ambedkar to inaugurate the Patit Pavan temple in Ratnagiri, which was open to all castes. Ambedkar could not attend the inauguration because of his work load in Mumbai. The admiration for Ambedkar was transparent. In one of his essays on social reforms, Savarkar would pour scorn on a culture that believes it gets polluted with even the shadow of an Ambedkar but thinks it gets purified with cow urine; a culture that sees God in an animal but treats a Godlike person such as Ambedkar like an animal. In January 1942, when Ambedkar turned 50, Savarkar praised his “personality, erudition and capacity to lead” and said: “The very fact of the birth of such a towering personality among the so-called untouchable castes could not but liberate their souls from self-depression and animate them to challenge the super-arrogant claims of the so-called touchables”.

Dhananjay Keer later wrote that the only three truly intellectual political leaders of that time were Ambedkar, Savarkar and Roy. However, Phadke argued in his 1966 essay that Savarkar was in fact quite unlike his contemporaries such as Gandhi, Nehru and Roy, who adapted their views as they learnt from experience. Savarkar remained rooted in the views that he embraced as a young man, falling prey to dogmatism. Ambedkar himself accused Gandhi of a similar flaw: “In the age of Ranade leaders depended upon experience as a corrective method to their thoughts and their deeds. The leaders of the present age depend upon their inner voice as their guide.”

Savarkar was also an uncompromising modernist — “a child of Enlightenment rationalism,” as the writer Pankaj Mishra, no fan of Hindu nationalism, has quite rightly pointed out. He strongly believed that India could be a successful nation state only if it embraced modern science, social equality, machinery and military power. His attacks on Hindu social practices were harsh enough for many religious organisations to pass resolutions condemning him. Savarkar welcomed the machine age as a way to liberate humankind from drudgery. Like many others in the Indian House group, Savarkar was deeply influenced by the utilitarian philosophy of Herbert Spencer, and had in an essay described Sri Krishna as the first utilitarian.

Savarkar was very clearly inspired by the ideals of European nationalism, especially the Italian Risorgimento. Like nationalists of every hue in that generation, the central question that Savarkar grappled with was how to integrate India into a territorial nation state, just as the Italians had done in 1860 and the Germans in 1871. Savarkar was famously galvanised by the example set by Joseph Mazzini, the revolutionary who helped integrate Italy into a united nation state. He was also an admirer of Kemal Ataturk, calling on Indian Muslims to learn from the Turkish example, and join the modern world rather than getting trapped in the pages of the Quran.

Another improbable person he had a high regard for was Lenin. Savarkar translated a Russian article on the revolutionary Soviet law giving women the right to choose their sexual partners as well as divorce their husbands. He never formally backed these ideas, but the very fact that he presented the translation for his readers to think over tells us a lot. In his Marathi memoirs, Narayan Sadashiv Bapat, once a member of Savarkar’s inner circle at Ratnagiri, who later became a Royist, wrote how Savarkar would urge his colleagues to read Lenin. Some lectures on Lenin were given by a young Nathuram Godse, who later committed the heinous crime of killing Gandhi, an act that put Savarkar in the dock. The scholar D. N. Gokhale writes in his Marathi book on Savarkar about how a meeting had been held at Savarkar’s house in Ratnagiri to discuss the Lenin biography written by Godse (a book that this writer has for long tried to find). Bapat also remembers that the Savarkar brothers, in their newspaper, passionately defended the communists accused in the Meerut Conspiracy Case.

Soon after he was released from internal exile, Savarkar was elected to preside over the prestigious annual Marathi Sahitya Sammelan in Mumbai. He welcomed newer Marxist and Freudian approaches to literature, but also added that reducing literature to only economic or sexual explanations severely limits its scope. The second half of the speech was incendiary — an incredible call to writers to put down their pens to pick up the gun, because their artistic freedom could only be protected under the umbrella of effective national security. Savarkar had touched upon a similar dilemma in one of his Marathi plays, where a young warrior tells Gautam Buddha that he too dreams of a world where poets rule, but he has to pick up the sword to defend his country till there are others in the world who do not follow the Tathagata’s message of peace.

That speech at the literary conference is one example of how Savarkar’s love of rhetoric could overcome his love of reason. As Janaki Bakhale of Columbia University perceptively notes in a recent essay on Savarkar: “Both Mazzini and Savarkar saw themselves as literary figures and succeeded more in the realm of writing than in politics. Neither was a systematic thinker. Both were cosmopolitan nationalists, stipulating that the nation should be based more on a common political project than on ethnicity, religion, culture, or language”.

In a review of Hindu Pad Padshahi published in the May 1926 issue of the Modern Review, the historian Jadunath Sarkar pointed out that Savarkar’s work on the Maratha rebellion against Muslim rule was an example of romantic rather than professional history writing. In a Marathi essay on the social reformer and writer Prabodhankar Thackeray — father of Bal Thackeray — the historian Y. D. Phadke mentions how the former would joke about the Savarkar style of history writing. However, Savarkar wrote to light the spark of armed revolution against British Rule rather than as a detached academic calmly balancing evidence. Another famous historian, R. C. Majumdar, wrote the introduction to Hindu Pad Padshahi.

The opening remarks made by Savarkar in this book give us some insight into his views on the communal question, which is where he most strongly departed from the mainstream of Indian nationalism as well as attracting the ire of generations of critics. It is well known that Savarkar was a relentless critic of the Muslim politics of his time, as well as the attempts by the Gandhian Congress to accommodate its demands. Savarkar asked during his presidential speech of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1937: “Are the Mohammedans ready to join … a truly national Indian State without asking any special privilege, protection or weightage on the fanatical ground that a special merit attaches to them of being Mohammedans and not Hindus?”

Savarkar argued that Hindus would be committing political suicide by abandoning their identity as long as Muslims refused to give up their identity as a separate people. There was no common ground for an integral nationalism, a position that Ambedkar too took in his writings on the partition of India. Savarkar’s key political point during these years was that the demand put forth during the constitutional negotiations in the last decades of British rule — that the Hindu and Muslim communities should have equal seats in a future parliament — in effect gave every Muslim citizen two votes while every Hindu citizen had just one vote. Savarkar was furious that this contradicted the key democratic principle that each person should have one vote.

However, he repeatedly said his final goal was not just a secular Indian State but a world commonwealth where human beings lived as human beings. He enigmatically ended The Essentials of Hindutva with the following statement: “A Hindu is most intensively so when he ceases to be a Hindu; and with a Shankar claims the whole Earth for a Benaras”.

Savarkar saw the central theme of medieval Indian history as a heroic Hindu rebellion against Muslim domination, led by men such as Prithviraj Chauhan, Rana Pratap, Shivaji Maharaj and Guru Teg Bahadur. Yet, Savarkar also argued in the opening pages of Hindu Pad Padshahi that it is the task of modern societies to overcome the strife of the past. One paragraph is especially resonant: “Especially our Muhammadan countrymen, against the deeds of whose ancestors the history under review was a giant and mighty protest, which we hold justifiable, will try to read (this book) without attributing, solely on that ground, any ill feeling by us towards our Muhammadan countrymen of this generation, or towards the community itself as such. It would be as suicidal and as ridiculous to borrow the hostilities and combats of the past only to fight them out into the present, as it would be for a Hindu and a Muhammadan to lock each other suddenly in a death grip while embracing, only because Shivaji and Afzul Khan had done so, hundreds of years ago.” He added that people should read history not to perpetuate the old strife but to seek a way out of it by identifying the causes of such strife.

However, Savarkar tied himself in a knot on this central issue of his politics. He was a passionate defender of Hindu political rights. He wrote incessantly about the clash between the two communities over centuries. He said that Hindus and Muslims are two nations, or two separate people. Yet, he also argued for a secular democratic state where both communities would live in peace, without convincingly explaining how the circle would be squared. (Savarkar used the word nation in the contemporary sense of a people rather than in the modern sense of a nation state.)

In a perceptive analysis, Ambedkar pointed out the fundamental contradiction in Savarkar’s quest to force two warring communities to live together in a common nation state, rather than accept partition. After complimenting Savarkar for his clarity as compared to the vagueness of Congress policy, Ambedkar wrote: “It must be said that Mr. Savarkar's attitude is illogical, if not queer. Mr. Savarkar admits that the Muslims are a separate nation. He concedes that they have a right to cultural autonomy. He allows them to have a national flag. Yet he opposes the demand of the Muslim nation for a separate national home. If he claims a national home for the Hindu nation, how can he refuse the claim of the Muslim nation for a national home?”

The parallels between Savarkar and the Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the father figure of the Israeli Right, are striking. What Jabotinsky wrote in the very beginning of his famous political tract, The Iron Wall, is very close to the Savarkarite view: “Emotionally, my attitude to the Arabs is the same as to all other nations — polite indifference. Politically, my attitude is determined by two principles. First of all, I consider it utterly impossible to eject the Arabs from Palestine. There will always be two nations in Palestine – which is good enough for me, provided the Jews become the majority. And secondly, I belong to the group that once drew up the Helsingfors Programme , the programme of national rights for all nationalities living in the same State. In drawing up that programme, we had in mind not only the Jews, but all nations everywhere, and its basis is equality of rights.”

“I am prepared to take an oath binding ourselves and our descendants that we shall never do anything contrary to the principle of equal rights, and that we shall never try to eject anyone. This seems to me a fairly peaceful credo. But it is quite another question whether it is always possible to realise a peaceful aim by peaceful means. For the answer to this question does not depends on our attitudes to the Arabs, but entirely on the attitude of the Arabs to us and to Zionism.”

Savarkar had a similar political programme, with the same internal tensions. These comments in the course of his presidential speech at the Calcutta meeting of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1939 are perhaps the clearest indication of what Savarkar meant: “The Hindu Sanghanists Party aims to base the future constitution of Hindustan on the broad principle that all citizens should have equal rights and obligations irrespective of caste or creed, race or religion, provided they avow and owe an exclusive and devoted allegiance to the Hindustani State. The fundamental rights of liberty of speech, liberty of conscience, of worship, of association, etc., will be enjoyed by all citizens alike. Whatever restrictions will be imposed on them in the interest of the public peace and order of National emergency will not be based on any religious or racial considerations alone but on common National grounds.”

“No attitude can be more National even in the territorial sense than this and it is this attitude in general which is expressed in substance by the curt formula ‘one man one vote’. This will make it clear that the conception of a Hindu Nation is in no way inconsistent with the development of a common Indian Nation, a united Hindustani State in which all sects and sections, races and religions, castes and creeds, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Anglo-Indians, etc., could be harmoniously welded together into a political State on terms of perfect equality.”

“But as practical politics require it, and as the Hindu Sanghanists want to relieve our non-Hindu countrymen of even a ghost of suspicion, we are prepared to emphasise that the legitimate rights of minorities with regard to their religion, culture and language will be expressly guaranteed: on one condition only that the equal rights of the majority also must not in any case be encroached upon or abrogated. Every minority may have separate schools to train up their children in their own tongue, their own religious or cultural institutions and can receive Government help also for these, but always in proportion to the taxes they pay into the common Exchequer. The same principle must, of course, hold good in case of the majority too.”

In an essay in the New York Times, the Israeli historian Avi Shlaim wrote that Jabotinsky was banking on the fact that Zionist determination would break the Palestinian national movement of the day, creating space for moderate Arab opinion to emerge, in turn creating opportunities for serious negotiations between the two communities. Is that what Savarkar also wished? It is hard to know.

Savarkar inevitably spoke in favour of political liberty, modernity, social reforms and industrial development. However, his burning passion was a strong nation state. Savarkar often argued that an effective democracy has to be backed by military power; he once wrote that swords and cannons define the boundaries and rights of states. A tricky question worth pondering over is whether Savarkar saw democracy as a building block of a strong Indian nation state or as a requirement in itself for citizens (as was the case with Ambedkar).

In a speech in 1961, as part of a Mrutyunjay Divas celebration in Pune, Savarkar argued he would prefer a strong dictatorship that is able to protect Indian interests to a weak democracy that is unable to do so. This was in contrast to his usual defence of liberty, a strange outburst by the lion in winter. Among the leaders he mentioned to bolster his case for military strength were Hitler, Lenin, Stalin, De Gaulle and, hold your breath, Mobutu Sese Seko of the Congo. He was also careful to add — echoing Mazzini — that the citizens of a strong nation would also eventually overthrow such dictators, as was the case with Napoleon.

This essay began with the excitement unleashed after Savarkar was released from internal exile. His subsequent political career was not very successful. One challenge was that he was at the head of a smaller party that did not have the organisational strength of the Congress. An equally important point that often comes up in Marathi writing on Savarkar is that he had become too much of a loner in his later years, even refusing to meet his old India House friend Mirza Abbas when he visited Mumbai in 1950. There was a tinge of bitterness of well, and it is worth speculating whether this was related either to the physical torture he had to experience in Cellular Jail or the fact that he had been overshadowed in national politics by Gandhi. Some of his London comrades said they missed the signature laughter that echoed through the rooms of India House in the old days.

Savarkar eventually failed to build an organisation to further his political programme. Keer writes that Savarkar could never nurture Shyama Prasad Mukherjee the way Gandhi nurtured Nehru. Others have speculated whether the style of leadership that Savarkar perfected while leading a revolutionary group was inadequate for an electoral party such as the Hindu Mahasabha, where the focus had to be building a mass base rather than individual acts of daring.

The stormy petrel of early 20th century Indian politics could never occupy the centre stage after his final release from incarceration. The socialist intellectual Narahar Kurundkar wrote in a Marathi essay that younger political activists who could have joined Savarkar had already been pulled into the Gandhian movement by 1937, while Savarkar was left in the company of older traditionalists who were incapable of appreciating his deeper political programme. That, says Kurundkar, was one of the grand tragedies of Indian politics.

Savarkar will always be a controversial figure, but there is no doubt this brilliant revolutionary needs to be understood better. The current debates about him are often based on flimsy grounds, and he is caricatured by both sides for partisan reasons. The time is ripe for a new generation of scholars to grapple with the Savarkar enigma.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest