Ideas

Where Shyam Meets Shiva: How Night Ragas Unravel The Several Destinations Where The Two Emerge Together

- The night ragas of Hindustani music represent that space where Krishna and Shiva appear to merge in a bhakta's imagination.

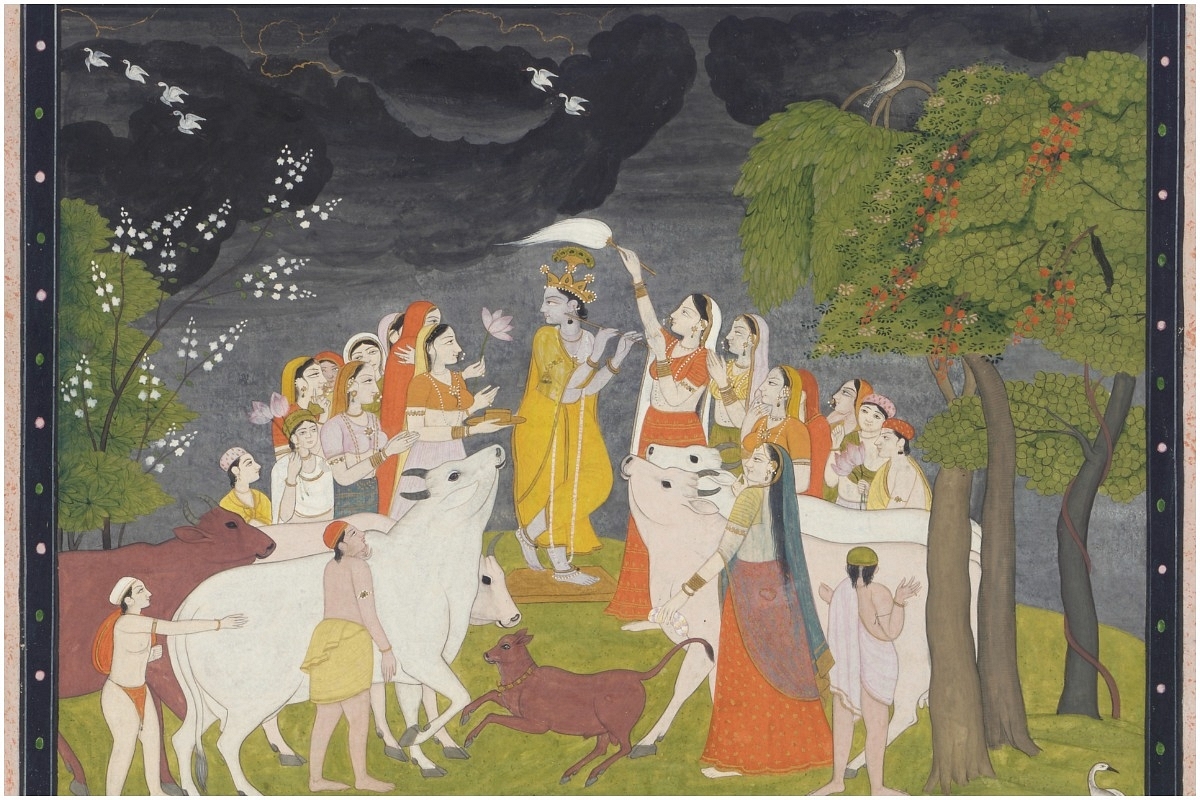

(Wikimedia Commons)

The Ganga of Kedar -- Shiva, and the Yamuna of Keshav -- Krishna,

originate in Uttarakhand. Devbhoomi is the first common ground from which flow the eternal representatives and prateek of Shiva and Krishna. There are other realms, seen and felt, heard, unheard, thunderous, where Shiva and Krishna appear to pull a bhakta, together, towards the Gangotri and Yamunotri of their eternal affection, towards grounds that emerge as similar, towards elements and colours that meet and separate. Initially.

Then, the two rivers, distinct, flow and take their own paths. One meanders towards Braj, the other towards Benaras.

Why am I mentioning Shiva when I should be singing only to Krishna on Janmashtami? Let me try to give the longest answer in the shortest sentence. Bhakti.

Krishna and Shiva. Where can they be found? In the rhythm and laya of the tandava and the leela, in naad, the sound of eternity that Shiva breathes out, the brahmanaada, the sound of Krishna's flute, darkness and blue, the colour of their encompassing jataa and kesh. In their Ganga and Yamuna, in Shiva's Nandi and in Krishna's gau, in the path opened by them for us, towards Kailasha and Govardhan. Composure. Eyes. Darkness. Blue. Music. Colour. Their vehicles. The parvats.

The night. The night ragas.

Ragas in Hindustani music, the night ragas, often present that stroke of blue, the broad and thin brush of darkness, where Krishna and Shiva appear to merge in a bhakta's imagination.

Malkauns. A raga often in use to paint and fill over the outlines of the billowing night of pining and love, and of bhakti.

They seem to appear together in Malkauns...

Breathed into the bansuri by Pandit Hari Prasad Chaurasia, who himself, as a musical entity, represents Krishna's own creation as our spiritual and civilisational heritage. In this composition, follow the meditative expanse of the madhyam and gandhar to understand the commonalities that engage with the playfulness of Krishna and the quiet gaze of Shiva.

...as if Shiva is telling Krishna, I keep my share of Malkauns, you keep yours, as the raatri of their kesh and jataa gently unfolds over the dark, dark contours of the Himalaya and the Govardhan.

A destination where I found Shiva and Krishna pouring their presence in art was in two artistes who performed as one. The duet -- of Pandit Rajan and Sajan Mishra. Pandit Rajan Mishra and Pandit Sajan Mishra Benaras defined -- in gharana, in depth of art, in playfulness, in their rendering of the bandish dedicated to Shiva and Krishna, and in ragas that seem to open the ear to the awakening beauty of Shiva and of Krishna.

When seen placed in darkness, the beauty emerges as boldly as a lamp does, at the base of the Govardhan, or snow on the peaks in the backdrop of Kedarnath, under the full moon.

Pandit Rajan Mishra passed away earlier this year due to Covid. This author could not gather the strength to write an obituary to Pandit ji. And yet, in all strength, I state that it was Pandit ji's art in the duality and singularity of his duet with his dear brother Pandit Sajan Mishra, where Shiva and Krishna would be offered compositions that stand unparalleled, unmatched, unbound, and will.

Pandit Rajan and Sajan Mishra represent Shiva's Kashi and Pandit Rajan Mishra would tell this author during several interactions how the boatmen on Kashi's Ganga inspired them in singing for Krishna.

Chhayanat. Chhaya -- the shadow, the delving hues of something on something, the shadows of the night on the moon or the moon on the night perhaps. The shadow of love on the moonlit washed ground of the leelas. The playfulness of love and love making in the leelas. Nat -- the main entity here and its play in Chhayanat is a stage in itself, meant to offer or to discover the glimmer of the peacock feather, the raas, Girdhari and the crescent moon.

"Mor bole" -- a celebrated bandish in Chhayanat is one that many, such as this author, chase, for the canvas of the raas, for the moonlight arriving in its rishabh. Pandit Rajan and Sajan Mishra build a gentle and patient progression into the early night, each moment of the raas and its intimate interactions with love.

The drut khayal, "Bhari gagari mori dhulkaye chhail", too, is a popular celebration of Krishna.

The sweet accusations against Krishna in the bandish have occupied us for generations and decades of singing and embracing this bandish. Pandit Rajan Mishra covers the context of Jamuna in immense depth and altitude of his art.

I choose Shivranjini. The transition from Chhayanat to Shivranjani is like the journey of Krishna himself. Some years ago, Pandit Rajan Mishra mentioned it to this author that there is one raga that's rarely used for singing bandish that's dedicated to Krishna. We were talking about ragas rarely used or sung. As it was destined to happen, Pt Rajan and Sajan Mishra sang Shivranjini at Delhi's Kamani Auditorium one evening. It was a concert I attended, to stumble upon several unfelt and unknown sorrows that are enclosed in the raga, and particularly in the context of Radha and Krishna.

I met the brothers after the concert. While I was touching their feet, as was the staple gesture on meeting them, they were as teasing as ever. Noticing that I had cried: "Suna, fir, Shivranjini?," Pandit Rajan Mishra asked, asking everything in just three words. The composition: "Radhe, tumhre nain Shyam basey". Radha, Krishna resides in your eyes, dear.

Shyam. Krishna. The darkness. Of the night. And Shivranjini.

Shivranjini. A raga meant for Shiva. To please Shiva when he is angry, perhaps. Kashi and Krishna, they were easily found in Pt Rajan Mishra and Pt Sajan Mishra's sadhana. Ash and tears blend well in the blue and the dark of Shyam, as Shiva watches over and pulls towards the inclusivity in both dark and blue. Explaining these common grounds in ragas, musically, in swaras, is a journey as vast as that from Braj to Benaras, for another time.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest