Magazine

1952 General Elections: Like An Exam For An Infant

- Studying the first general elections of a young republic reveals the permanent and impermanent traits of the Indian democracy.

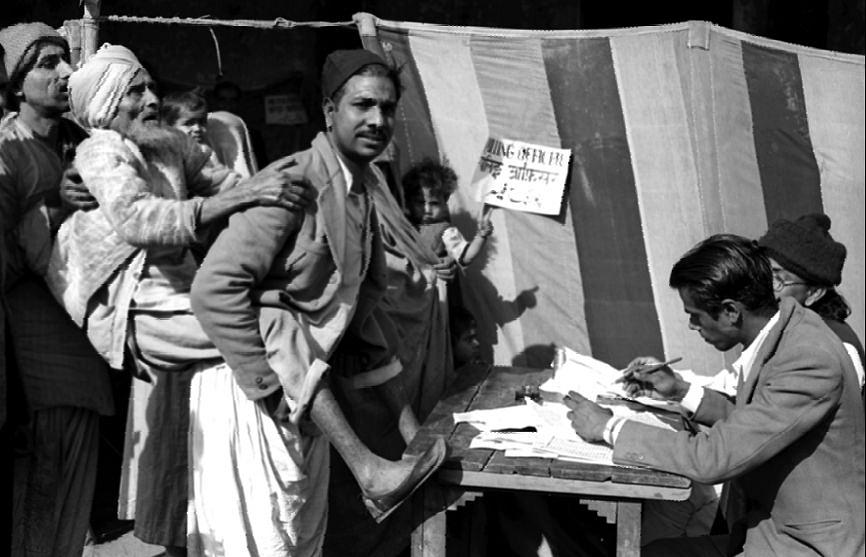

A blind old man is being brought to a polling booth by his son, to help him to cast his vote during the first general elections in 1952, near a polling station in Jama Masjid area in Delhi.

2019 is a big election year in India — the 17th general election in independent India and the largest that we have ever witnessed. This might be a good time to revisit the elections of the past, and there is no better place to start than the first general elections held in 1952. A historic election when a largely illiterate nation, with less than 20 per cent literacy, exercised the right to vote — a right extended universally to all adults by the newly-promulgated Constitution.

This wasn't of course the first election held in India. There had been several elections for both the central and provincial legislative bodies since the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919. The first ‘general’ election for the central legislative body was held in 1920. There were several more in 1923, 1926, 1930, 1934 and 1945, as well as major provincial elections, notably in 1936-37 and 1946. But the franchise was limited to a very small minority of the population in those elections. So 1952 is the first election that engaged the whole of Indian society.

Even though this was such a major event, the turnout was not too special — it was fairly low at 45.7 per cent. The outcome was also very predictable with the Indian National Congress emerging as the clear winner with 364 seats and a vote share of 45 per cent. However, it is worth emphasising that even in this very first election, 55 per cent of the people did not vote for the Congress – the party that had been central to the nationalist movement and the freedom struggle.

Fragmented Political Landscape

Now let's take a look at some facts concerning this election. There were as many as 53 parties in the fray. Of these, 22 parties won at least one seat. While 53 may not seem like a high number, it is worth noting the fragmentation of the political landscape even at such an early stage.

Let's take a look at the 22 parties that won at least one seat. We see a poor correspondence between vote share and seats. Some examples:

- The Socialist Party with 10.6 per cent of votes won just 12 seats

- Communist Party of India (CPI) won 16 seats with just 3.3 per cent of the votes

- The People’s Democratic Front (PDF) won seven seats with 1.3 per cent votes

With the exception of Congress, parties with a strong presence in certain regions like CPI and PDF enjoyed more success than a national party like the Socialist Party, whose much greater vote share did not translate into a large number of seats

Parties With At Least One Seat In The 1952 Lok Sabha

Assessing The Ideological Firmament In 1952

Today, we tend to think of the Congress as the nation’s pre-eminent centre-left political party. But this was not quite the case in 1952. Back then, it probably made more sense to think of the Congress as a centre-right formation, albeit led by a rather Left-wing leader in Jawaharlal Nehru.

In 1952, the prime opposition to the Congress emanated from the Left, and not the Right. The Right was still a very marginal player in 1952. The Hindu nationalist vote was split between several parties and the Swatantra Party's formation was still seven years away.

Here is an attempt to classify the 22 political parties into five different ideological categories, with Congress being a category unto itself.

Ideological Categories In 1952

Here is how the vote shares and seats stacked up among these categories in 1952.

Seats And Vote Share By Category

A couple of observations are in order here:

- In the first general election, parties that could be categorised as ‘Left wing’ got 23 per cent of the votes and 50 seats out of 489. Much more impressive than the corresponding figures for the ‘Left’ in 2014.

- Both the Left and the Right were heavily splintered in 1952. While the Left vote to this day remains splintered, the Right vote has both increased its share of the pie and also consolidated behind a single party — the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — the successor of Bharatiya Jan Sangh.

So let's take a closer look at each of these categories — at the parties which challenged the Congress.

The Left:

Among the seven political parties that could be branded as belonging to the ‘Left’ in 1952, the most important by far was the Socialist Party, with over 10 per cent of the national vote and Jayaprakash Narayan (popularly known as JP) as its tallest leader.

The CPI, interestingly, was the second largest party in the Lok Sabha in terms of seats, with 16 of them. Its vote share, however, was less than one-third of that of the Socialist Party.

1957, the year CPI came to power in Kerala, was only five years away. Interestingly, in 1952, the party did well outside Kerala. Among their 16 seats, eight were in Madras state, five in West Bengal, one in Orissa and two in Tripura and none in Travancore/Cochin.

In contrast, the Socialist Party had a more diverse presence across more states than CPI. Their 12 seats were won across eight separate states.

The Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party was another fairly major party accounting for nearly 6 per cent of the votes. It was founded by Acharya Kripalani, a stalwart of the freedom struggle. Six of its nine seats were won in Madras. Soon after the election, the party merged with JP's Socialist Party.

The People's Democratic Party was a breakaway of the Communist Party which won all its seven seats in Hyderabad. Many of its leaders were involved in the Telangana rebellion of the late 1940s against the feudal lords of the region.

Now, let's move to the Right.

The Right

The consolidation of the Right was still a distant dream in 1962. The Bharatiya Jan Sangh had a vote share of 3 per cent that year, far lower than the vote share of major Left wing parties like the Socialist Party and Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party. Interestingly, two of the three seats won by the Jan Sangh were in West Bengal, a region we do not typically associate with the Hindu Right today.

While the Jan Sangh was the most important party representing the Hindu Right, there were others in the fray. Ram Rajya Parishad and Hindu Mahasabha won seven seats between them. This was four seats more than Jan Sangh, and with a combined vote share as high as that of the Jan Sangh.

While Hindu Mahasabha needs no introduction, the Ram Rajya Parishad was a party established only in 1948. Founded by Swami Karpatri of Dashanami Sampradaya, it was a traditionalist party that led the agitation against the Hindu law reform of the 1950s.

Among the other parties on the Right (outside of the Hindu Right), we had the Ganatantra Parishad. This was a party dominated by princes and landlords, but with a regional Orissa focus. All six of its seats were in Orissa. Later, it became a part of Swatantra Party in the 1960s.

The other ‘conservative’ party was Krishkar Lok Party headed by N G Ranga. Ranga, a critic of co-operative farming, would later collaborate with Chakravarti Rajagopalachari to found the Swatantra Party.

Now let's move to the subaltern/caste-oriented parties.

The Subalterns: Caste-Based/Minority Focus Parties

The Scheduled Caste federation was headed by none other than Dr B R Ambedkar. Interestingly, Ambedkar lost the election in 1952 against the Congress candidate. This party was founded in 1942. It later morphed into the Republican Party of India in 1956.

Two caste-based parties — Tamil Nadu Toilers and Commonweal — won seven seats in Madras. These two entities were both Vanniyar parties focused on serving Vanniyar interests. Their somewhat pretentious names are amusing, given their agendas which were no doubt parochial and narrow.

One may notice the absence of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in this list. That is because the DMK decided to boycott the 1952 elections with this protest:

“In order to show our protest to the Indian constitution that was prepared according to the dictate of a single party [Congress Party] without understanding the views of the Dravidians … Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam would not field candidates in the 1952 election…”

Parties With Statehood Agenda

Among regional parties that called for a separate province or autonomy, we had three outfits — the Jharkhand Party, Shiromani Akali Dal and the Travancore Tamil Nadu Congress Party.

Shiromani Akali Dal was a Punjab-based party that would later lead the Punjabi Suba Movement for a separate state. It is worth noting that in 1952, there existed a larger East Punjab province that included Haryana. There also existed Patiala and East Punjab States Union — a state comprising of eight princely states.

Jharkhand Party grew out of the demand for a separate Jharkhand state. Interestingly, its demand for a separate state materialised in 2000.

The Travancore Tamil Nadu Congress Party was another regional outfit seeking a separate Tamil state for the Tamil speaking regions of the Malayali majority Travancore-Cochin province.

That was an overview of all the parties that opened their account in 1952. But we have not discussed the Congress and its performance yet.

Congress Performance In 1952

The Congress, not surprisingly, was a very clear winner with 364 seats and 45 per cent of the votes. It swept most states. But what’s striking is that it was particularly dominant in the Hindi belt. Notice the percentage of seats won by Congress in some of the major states of north India:

However, the party was far less dominant in states like Madras and Orissa, where it was up against regional parties like the Vanniyar parties in Madras, PDF in Hyderabad and the Ganatantra Parishad in Orissa. It also struggled in Rajasthan, where the Right wing parties put on their best show with Jan Sangh, Krishikar Lok Party and Ram Rajya Parishad winning five out of 20 seats.

Multi-Seat Constituencies

Besides the results, it is also worth noting another feature of the 1952 elections that distinguishes it from general elections in our times.

Until the 1960s, the Lok Sabha elections had multi-seat constituencies. In 1952, though the Lok Sabha had 489 seats, there were only 401 constituencies in all. 314 out of the 401 constituencies had one seat, 86 had two seats and one had three seats. These multi-seat constituencies existed for the purpose of reservations, with the same constituency electing one general and one SC/ST candidate, an example being Allahabad East, which elected two candidates, both from Congress — Jawaharlal Nehru and Masuriya Din (a Pasi SC candidate).

Takeaways

That brings us to the conclusion of this survey of the first major general election held in Indian history. A key takeaway from this examination is that the Congress was far from being the only player in town in 1952. What caused the Congress to win with a thumping majority was the fragmentation of the opposition, on both the Left and the Right.

The other takeaway for us is the decline of the Left over the years, relative to where it started in 1952. The Left parties of all hues accounted for 23 per cent of the vote in 1952. In 2014, the share of the Left was barely 5 per cent. A huge change.

The third takeaway is of course the opportunity lost by the Right back in the 1950s-1960s by not consolidating itself under a single banner. Notice the fragmentation between Jan Sangh, Hindu Mahasabha and Ram Rajya Parishad even in this election. In the 1960s, the Right yet again failed to consolidate, as the Jan Sangh-Swatantra Party alliance never materialised until 1971 when it was too late.

Above all, 1952 election reminds us of the transience of political life. There are few things that we can take for granted in politics, and that many of the parties that are dominant today may be altogether non-existent a few decades from now.

There is much to learn for all parties concerned from this examination of our nation’s politics when it was still very young.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest