Magazine

Before Rao, After Rao

- Too little credit has been given to the man who actually conceptualised and drove economic reforms—P.V. Narasimha Rao.

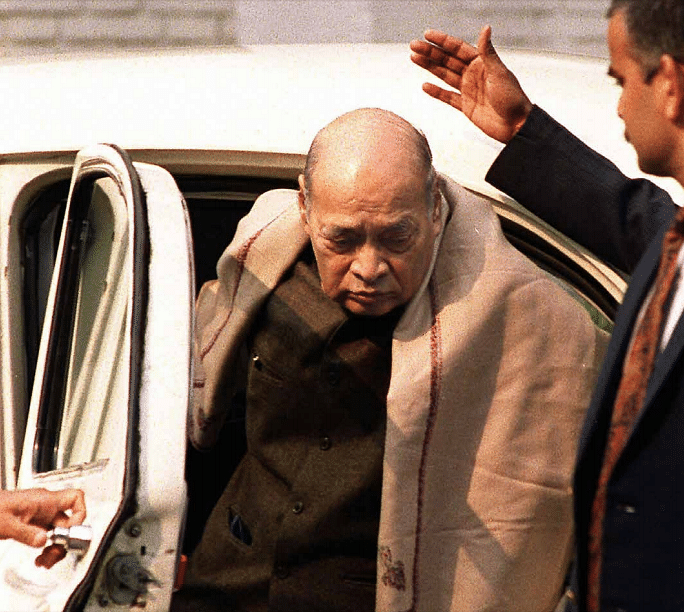

PV Narasimha Rao (RAVEENDRAN/AFP/Getty Images))

B NR should refer to the period of free India’s history Before Narasimha Rao. And ANR, After Narasimha Rao.When I meet young graduates who finished college in the last 10 years and try to explain to them our country as it was BNR, they simply do not understand. And yet, I think it is so important that they should know, lest we slip back into the dark ages again.

Firstly, there was a conviction that not only was India a very poor country, but that it would always remain poor. As a corollary to this national poverty, it was assumed that we would always be condemned to buy shoddy goods.

Our NRI cousins were almost like royalty. They not only drove good cars, they ate better chocolates, wore better underclothes, had better gadgets and above all had great confidence. We were in awe of them.

Whenever they landed at airports at midnight, we would be there, waiting to receive them. They wore fancy jeans (just imagine—we thought of lowly jeans as fancy items), they carried Walkmans, they had fine wristwatches and shoes that we could never dream off. We did not even know that there existed products called deodorants and disposable razors which were commonplace for them. They talked glibly and casually about watching different TV shows and movies on their VCR. We were acquainted only with the TV set in our neighbour’s home, where all of us gathered to watch Chhayageet and Chitrahaar.

Our neighbour, a person of great influence, had a black rotary phone. Our NRI cousins had never seen a rotary phone, which they thought of as a Graham Bell antique! We could not afford an air cooler, let alone an air conditioner—but the great cousins lived in homes that were centrally heated in winters and centrally cooled in summers.

Today my young graduate friends have the same laptops, smart phones, handbags, jeans and cosmetics as their NRI cousins—who are no more royals, just ordinary folk like us.

In the BNR days, Indian businesses had to deal with the JCCIE (Joint Chief Controller of Imports and Exports), the DGTD (Director General of Trade and Development) and the CCI (Controller of Capital Issues). Businesses were “controlled” at every step. Most of the time of senior employees was spent in figuring out as to which item was moving from the restricted list to OGL (Open General License) and when.

The whole point of being in business was to try and see how to maximise Duty Drawbacks and how to leverage the rare and precious paper known as an Import License.

One of the most profitable lines of business was to be a ghost exporter to the Soviet Union under the rupee-rouble trade programme. If you could wangle a government license to export basmati rice to the Soviets, then, by God, you had a license to print money. But such licenses were available only to the best connected folks in distant Delhi.

And then there was the MRTPC (Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Commission). Virtually all mid-sized companies were under this tyrant’s microscope. The august MRTP Commission was expected to ensure that no Indian company ever grew.

There were interesting employment opportunities too. You could become a clever Delhi fixer. You did not even have to get me licenses or approvals for my company. I would pay you just to suppress the license approvals of my competitors. And then there was FERA (Foreign Exchange Regulation Act). What a wonderful act it was! I had to do nothing except get a license. I could then go to any foreign company and tell them that the only way they could get into India was to give me 60 per cent share of their business, even though I brought nothing else to the table, but the license.

FERA had other aspects to it. Under FERA, any Indian could get $100 every three years to travel abroad. If you went more often, all you got was $8. I remember once being stranded at a foreign airport when my friend forgot to meet me when I landed. I had $8 which would have sufficed to get me a taxi to take me out of the airport and dump me on the street. I was expected by the Reserve Bank of India (who thought they had done me a favour by letting me have $8) to walk the next 10 miles, I suppose.In the stockmarket, we had something known as “budli”. Ask any of today’s Finance MBAs, and they will roll their eyes. Not that too many people understood budli. But everyone understood that there were cartels of brokers and making money by means of insider trading was just the way India that is Bharat operated. There was no SEBI. And who ever heard of fines when CEOs gave friendly tips to…their friends, who else!

We have come a long way, but every time I hear a sarcastic remark about those of us who wear suits and boots, I keep thinking of paan-chewing, dhoti-clad brokers whose cartels ruled Indian financial markets. Will we go back to those days in our anxiety to do away with suits and boots?

Today we buy Korean refrigerators, Indian cars (from Tata and Mahindra who were earlier prohibited from making cars), we travel relatively freely, we still have too many inspectors, but luckily not that many controllers.

The ANR world is one of modest hope, considerable energy and great enthusiasm. We can actually look forward to being RIs (Resident Indians) and not be consumed by envy when we meet NRIs.

Life is undoubtedly less comfortable for businessmen who relied on their skill for getting licenses in order to get wealthy. Life has become impossible for dhoti-wearing budli brokers who ruled the stockmarket. And the world has become a “neoliberal” hate object for trade unionists who hated computers (even if their children are happily writing code). But for ordinary businesspersons and middle class people, the world is much less hostile.

It is also an optimistic one for those aspiring to enter the middle class. They need not live with the feeling that they are cursed forever to be poor people in a poor country. The criticism that the ANR world has not done enough for the bottom quartile is not an insignificant one. But at least, we now talk of lifting them up—not of bringing everyone down. That is why we must all hope and pray that we do not reverse course.

The author is the former CEO of MphasiS, and was head of Citibank’s Global Technology Division. He is currently the Executive Chairman of Value and Budget Housing Corporation (VBHC), an affordable housing venture. Rao is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Swarajya.

This article was published in the July 2016 issue of our magazine. Do try our print edition - only Rs 349 for 3 print issues delivered to your home + 3 months digital access. Subscribe now!

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest