Magazine

TeamIndus: The Dream Is Still Alive

- A highly underrated private mission was aiming to put a rover on the moon. Everything was moving on track, but the exploration fell apart right when it was gaining momentum.

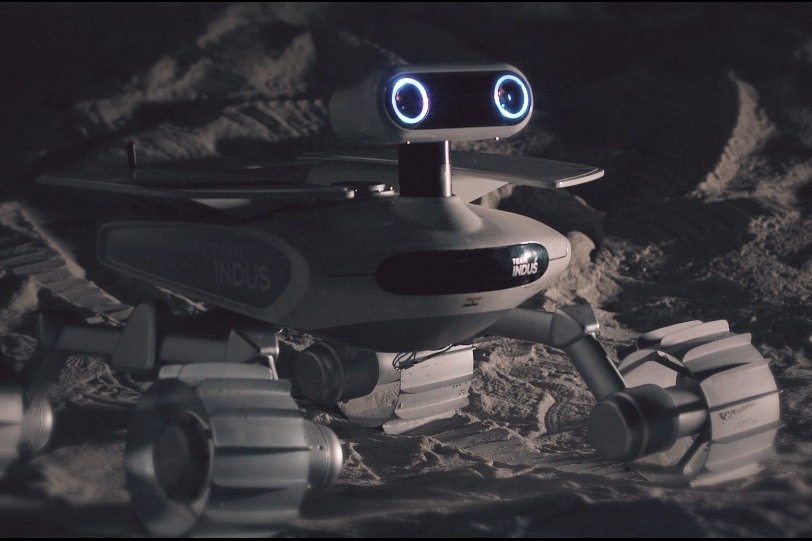

The ECA rover developed by TeamIndus.

Looking up at the night sky from India, one may point to a part of the moon that may look like a pair of hands, believed in Hindu mythology to be those of Ashtangi Mata, the mother who sent her twins up into the sky to be the sun and moon. These hands, which are seen as an old man or, alternatively, as the face of a man (among other things) in the West make up an area of the moon that came to be born from the fierce strike of a protoplanet-sized object – 250 kilometres in diameter – 3.8 billion years ago, close in time to the birth of our planet. The resulting dark lava plain, spread 1,200 km across, was christened 'Mare Imbrium', Latin for 'sea of showers' or 'sea rains'.

It was here, in this curious geological puzzle on the moon that is littered with grooves and gashes, that the Chinese rover Yutu landed in December 2013, and where five years later, in 2018, India was set to touch down by way of an unprecedented private mission.

The ball for this highly underrated operation got rolling in 2010 when a daring Indian private aerospace player called TeamIndus formed a young, skilled, and ambitious team to compete in the Google Lunar XPRIZE. According to the terms of the contest, a largely privately-funded space company had to put a rover on the moon, get it to move a distance of 500 metres, and capture and beam high-definition video and pictures back to Earth. TeamIndus was the only Indian entry in the race, and in no uncertain way, a last-minute one at that. Representing India in the contest was their motivation. As the company’s co-founder Dhruv Batra told Swarajya earlier this year, they felt like “if there was a competition of such a large magnitude happening anywhere, India had to have a representation in it”.

And represent they did. After an early phase, when they made mistakes amidst uncertainty on whether they would find acceptance or be actually able to pull off a feat of this enormous magnitude, things started to fall in place for the team. Backed by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), some of whose towering figures, like Krishnaswamy Kasturirangan – who conceptualised the successful Chandrayaan-1 moon mission, were mentoring the team at nearly every important stage. TeamIndus was taking giant strides.

The technology, which was the most critical part of their operation, underwent several stages of development and testing. The spacecraft design, which began taking shape as early as 2012, went through numerous iterations over the years. It was tested for landing and imaging in December 2014 by an international jury of five rocket scientists – and the test proved successful. TeamIndus won a prize of $1 million for the successful landing – a clear sign that they were on the right track.

Similarly, the rover 'Ek Choti si Asha' or ECA, which was to move across the surface of the moon, was shaped and reshaped by improvements over several years. The resulting ECA 5.0 version, which was a step up from the previous models in several respects, including upgraded cameras, was ready by June 2016, and a year later, with some improvements thrown in, an upgraded rover was ready and raring to go with the mission date less than a year away.

At the end of 2017, TeamIndus space technology was reviewed by six members of the Google Lunar XPRIZE judging panel and the view was unanimous. They all came away impressed with what had been created by a “small team with a big heart”, as director Chanda Gonzales described at the time. The chairman of the panel had said, “we have come away from this rigorous exercise impressed by the readiness of TeamIndus. They are clearly on the right trajectory to make history.”

At the time, even as they were collecting laurels on the technical side, the company was stoking public imagination, too, with even an anthem, composed by Ram Sampath in collaboration with singer Sona Mohapatra and band Sanam, set for the mission. Fair to say, a momentum was building up for this private moon exploration project to succeed despite reports, especially the two-part series “Does TeamIndus still have a shot at its moonshot” in The Ken, suggesting that TeamIndus was facing a problem of funds and the mission was standing on shaky ground. There was still, however, a sense of cautious optimism about the company’s chances.

And then came the bombshell, some would say not unexpected. TeamIndus and ISRO’s commercial arm, Antrix, called off their launch contract signed for the mission in January 2018 – the TeamIndus spacecraft was set for launch to the moon aboard ISRO’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, but now that was not to happen. That dealt a blow to the aerospace start-up as they were left carrierless, and marooned in their journey, with the announcement coming just a couple of months before the contest deadline of 31 March 2018.

The cancellation of the launch contract was linked to TeamIndus’ inability to pay up for the launch service – the same paucity of funds that was talked about in 2017 but not taken, perhaps, with as much seriousness as it deserved. The cautious optimism from before was quickly withering away. The grand Indian moon launch – or “Har Indian ka moonshot (every Indian’s moonshot)”, as the company’s slogan went – that was to be a spectacular moment for India, and Indian industry, was in the end not to be, even though TeamIndus kept scampering through to find a launch provider outside the country. The dream of seeing a rover traverse on the moon through an operation designed by an Indian private player had fallen apart.

In the months since, TeamIndus has not given up on the dream. It is still committed to becoming the world’s first private space exploration mission. Its challenge, besides sorting out the funds and getting the launch technology absolutely dead-on, is to find an alternate launch provider. In January this year, TeamIndus revealed that they had raised a little over 50 per cent of the cost of their moon mission, which is pegged at $60 million. They will have to find ways to plug that gap. Whether private industry will step in to improve the chances of the mission’s success remains to be seen.

The road ahead is tough, and there are no two ways about it, but that is to be expected; the programme, after all, promises to open doors to space exploration beyond the reaches of Earth and moon, and create a space ecosystem that could serve the needs here on Earth as well as beyond. There may be plenty of critics, who would argue instead for investment on Earth rather than beyond.

However, it must not be forgotten that it was because of the investment in space technology in the yesteryear that today we have such applications of everyday use as the global positioning system (GPS), which helps us navigate here on our planet, or direct-to-home (DTH), using which we earthlings are able to watch television directly through satellite transmission. From the technology that TeamIndus is striving to develop, governments or private players will be able to help out in critical areas like disaster relief and provide connectivity to remote areas across the country and elsewhere, and possibly be able to assist, for instance, in providing medical assistance virtually to people who may have no access to medical care in the vicinity. Such are the gains to be had from space exploration missions, and to see them somehow as far removed from everyday reality would be a folly. At the same time, there should be no pretence about striving to expand the frontiers of scientific knowledge and discover new things – and for its own self rather than for geopolitical or economic gains.

Today, we may not be able to identify all the exact applications that will emerge from a moon mission of the kind TeamIndus is striving to undertake, but we know from the past that it is likely to produce something substantial. If not now, then eventually and could even be something extraordinary – perhaps pave the way for humans to live on Mars?

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest