Magazine

The Next Frontier: The New Wave Of Innovation Will Come From Biology

- Biology could be the next hot area for disruption for Indian startups, both in food and agriculture, and medicine and healthcare.

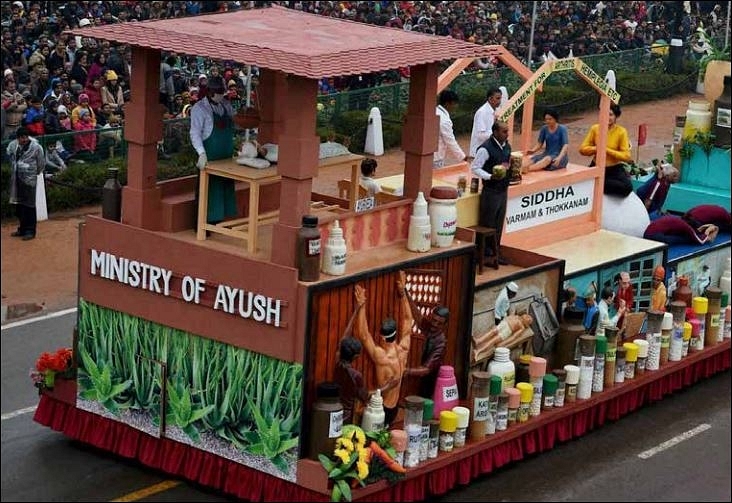

The Ayush Ministry has certified about 12,500 ayurvedic products.

There is no doubt that computation has induced enormous innovation, bringing many upsides as well as downsides to mankind, the recent Facebook scandal being an example of both: connectivity versus privacy. However, it is increasingly possible that biology is where the next wave of innovation will come from. If you define biology broadly, it is evident that agriculture and health both come under that rubric, and it’s fundamental to the very survival of Homo sapiens.

Let us consider briefly two areas in biology: the future of food, and the untapped wonders of medicinal plants.

Food And Agriculture

A recent study “Sustainable Food Security in India” in PLOS One paints a grave picture of poor nutrition in India, and predicts that based on climate change, low productivity and losses in the supply chain, India will have to import food massively to feed itself. Another report “What’s in store for the meat industry in India” contends that traditionally vegetarian India is moving towards meat, especially chicken.

There are several major problems. One is that India is one of the most water-stressed nations on earth, as misguided farm policies (including the Green Revolution and free electricity for farmers) have caused excessive exploitation of groundwater. With Himalayan glaciers shrinking and rivers damaged by deforestation, reduced precipitation and sand-mining, India is on the way to a crisis in water. There is also the strong possibility that China will divert the Brahmaptura/Tsang-po northwards in Chinese-occupied Tibet.

Another problem is that we have allowed our traditional genetic variants to die out, in the (in hindsight) foolish pursuit of Western strains of staple crops as well as livestock, with predictably disastrous results, as in the preponderance of A1-milk-producing Bos taurus taurus as opposed to the (better) A2 Bos taurus indicus, the native humped zebu cattle.

In grains, a report in the Hindu Business Line, “Speciality rice varieties of Kerala are storehouses of nutrition” suggests that we have abandoned well-adapted, nutritious local varieties for high-yield, nutrition-poor Green Revolution varieties (some may remember IR-8 from the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines). In addition, we have dropped coarse grains (such as jowar, ragi) from our diet and have taken on the problems of diabetes that come with wheat and especially rice.

A third problem is that the agricultural supply chain is severely deficient. Even though India is the number one or number two producer in the world for many vegetables and fruits, as much as half the crop is lost to pests or rots in the fields or does not provide an adequate return to the farmer. There are economic reasons such as the lack of price-discovery/futures markets/crop insurance, and too many intermediaries, as well as the near-absence of large-scale storage and processing capabilities, because successive Indian governments neglected agri-infrastructure spending. Besides, consumers face the problem of excessive pesticide and chemical use in food (including in the sale of spoiled meat and fish dolled up with ammonia etc).

Is there a way out of all this? There are several, and I have seen some startups working on a few ideas. One is in the use of sensors, drones, satellite feeds, big data and machine learning to make agriculture more efficient through highly-customised processes that use just enough water, fertiliser and pesticide, for instance see the World Economic Forum’s “How farm drones will transform the way your food is grown”. Another is in the use of blockchains to manage the supply chain to guarantee sourcing. For example, customers may be able to get truly organic, pesticide-free produce.

But there are even more radical solutions possible. In the long run, I believe the biggest change may come from the new technology of clean meat. I gave an overview of the state of the art in that domain in “Generating Meat in the Labs” in these pages in November 2017. Briefly, clean meat either converts vegetable protein to be a close analog of meat, or it grows genuine meat tissue in sterile lab conditions. These technologies are now coming close to market.

I had a chance to meet an interesting Chilean startup, the Not Company which has specialised in “not” products, for instance, Not-Mayo, which is indistinguishable from the real thing (I can vouch for it, having taste-tested their egg-free mayonnaise), and Not-Milk. These are vegan products made entirely from vegetables, and they have a bright future as both conscientious users (aware of the huge environmental cost of animal husbandry) and mainstream users find that the product costs the same, tastes the same, and they can virtue-signal with it.

What may be particularly exciting about the Not Company is their artificial intelligence system Guiseppe, named after a medieval European artist, who specialised in human portraits made entirely from vegetables and fruits. Guiseppe has the potential to provide plant-based analogs for virtually any food, with the appropriate texture and taste. If Indian innovators could create Guiseppe-like solutions (or license the technology) for clean meats/milk/eggs etc, a lot of the wasted fruits and vegetables in India could end up in high-value-added products.

Medicinal Plants, And Healthcare In General

The fact that a Chinese scientist won a Nobel Prize in medicine recently by deriving products out of a traditional Chinese medicine is a hopeful pointer for Ayurveda and more generally AYUSH in India. There is a tremendous amount of medicinal botanical knowledge gathered over centuries that is languishing in Sanskrit texts unread, but there is some reason for optimism.

The Hortus Malabaricus is a monumental 12-volume encyclopaedia of the flora of the Western Ghats, written in Latin for a Dutch official in Kerala, Van Reede, around 1783. This is still one of the finest sources of information about medicinal plants, and after it was translated into English recently by Professor Manilal and published by Kerala University, it has been a source of “prior art” to fend off predatory bio-piracy.

The source material came from the palm-leaf manuscripts in Malayalam of the vaidya family of Itty Achuthan Kollat, the principal author, who, along with three Konkani Bhat vaidyas, compiled this staggering work of intellectual property.

There is a Tropical Botanical Garden and Research Institute in Palode, outside Thiruvanthapuram, and it has an Itty Achuthan Vaidya Memorial Herbal Garden, which I visited. In a conversation with the director of the institute, Dr A G Pandurangan, who was kind enough to give me an hour of his time, I learned a number of interesting facts. It is now considered almost certain that Carl Linnaeus, the 18th century European botanist, who is said to be the founder of the classification of plant species, studied and referred to the detailed drawings and descriptions in the Hortus.

On five acres of land, the garden is now growing all 674 species of medicinal plants described in the Hortus, except for 23, and there they have tried to simulate the typical conditions under which they flourish. There is a small building and a life-sized statue of Itty Achuthan in a posture where he is checking the pulse of a patient. There are roughly 12,000 Ayurvedic formulations that are in regular use by vaidyas, but many are yet to be documented, and their active ingredients yet to be identified. There are apparently 7,500 species of medicinal plants known, of which 3,000 species are coded in different systems, and the rest are the traditional knowledge systems of tribal populations.

As an example, there is Arogya Pacha, Tricopus zeylanicus travancoricus, an intellectual property of the Kani tribe of Agastyamala Biosphere reserve nearby. Its leaves and fruits have a rejuvenating property without any steroids, and is also useful for sports medicine. In an arrangement with the Kani tribe, a commercial product has been brought out by Arya Vaidya Pharmacy, Coimbatore, and royalties are accruing to the tribe.

Another example is guggul from the Rajasthani tree, Commiphora mukul, whose gum can be used in treating arthritis and cholesterol and is an ingredient, for instance, in the Ayurvedic guggula tiktakam for skin diseases, including non-healing wounds.

The fact that traditional healer Laxmi Kutty Amma, also from the Kani tribe in nearby Kallar, Thiruvanthapuram district, was awarded a Padma Shri in 2018 is an indication that, at long last, the native healer is getting well-deserved attention. As a specialist in treating poisons using medicinal herbs, especially for snakebites, she is an embodiment of knowledge passed down orally over time.

Ethnopharmacology and ethnomedicine are areas where Indian innovators can arrive at equitable deals with the traditional holders of the IPR. The World Intellectual Property Organisation recently brought out a new publication, “Documenting Traditional Knowledge — A Toolkit”, that may be put to use immediately.

There is an estimated medicinal plant demand of Rs 4,000-5,000 crore, growing at as much as 15 per cent a year. Ayurvedic companies typically depend on tribal communities to procure the plants from forests, as opposed to cultivating them. Often, alas, the primary producer may get a paltry amount, and that needs to change: an equitable amount of royalty needs to be paid by commercial end-product providers.

Now that Ayurveda has a bit of cachet, a proper certification and testing mechanism needs to be implemented, that can also monitored by AYUSH, which has certified about 12,500 products, although it has codified in the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library nearly 800,000 Ayurvedic formulations. The Chinese have managed to keep control over their traditional medicine, with standards defined and controlled by China; whereas in India these may end up being undermined, or, worse, owned by foreigners.

There are also Geographical Indications (GI) which have been subverted: for instance, Texmati, which is a cross between basmati and an American long-grain rice, has been sold in the US for some years. There are large numbers of Indian wild and cross-bred rice variants including black rice from the Northeast that are appropriate candidates for GIs. However, the numbers of GIs or patents generated remains disappointingly low. I think even Arogya Pacha does not have an Indian patent yet, and certainly not global patent protection.

In addition to Agastyamala, a tropical forest, there are several other Biosphere Reserves in India, including the Nilgiris (Bandipur/Nagarahole/Mudumalai/Wayanad) in the South, and Sundarbans and Nandadevi elsewhere. Every one of these is likely to have its own set of medicinal plants and traditional techniques for using them, preserved in the lineage of the local populations. (Interestingly enough, both Agastyamala and Nandadevi have claimants for the legend about the mountain with the mrta-sanjeevani plant that Hanuman picked up and carried to Lanka! We can safely assume that vaidyas have treasured the medicinal plants in both locations for long.)

Substantial knowledge exists about medicinal plants and Ayurvedic formulations; by collaborating with the AYUSH Ministry, and creating mechanisms to give royalties to the ultimate traditional knowledge owners, innovative Indian firms should be able to certify, manufacture and bring to market these bio/ethno-pharmaceutical products.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest