Magazine

“There Is A Unique Relationship Between Figural Imagery And Ideas In Hindu Art.”

- In an interview with Swarajya, Dr Heather Elgood shares her views on how Asian art is collected, viewed, perceived and conserved across the globe.

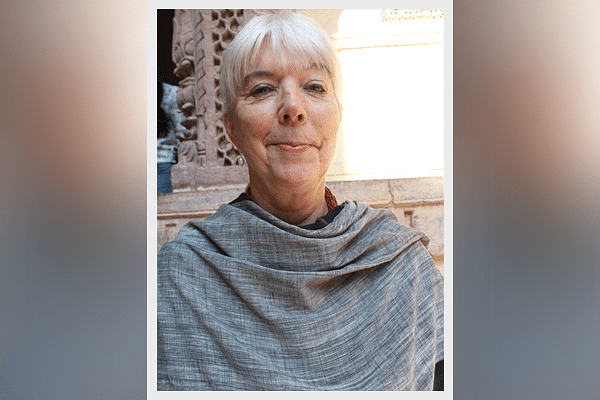

Dr Heather Elgood

Dr Heather Elgood is course director, Post-Graduate Diploma in Asian Art, Department of History, Art and Archaeology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. She was awarded an MBE in 2015 for “Services to Higher Education and the Arts”.

Dr Elgood’s course at SOAS is an object-based study of the arts of Asia, with students who come from diverse academic and professional backgrounds, getting access to reserve collections at the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

SOAS occupies a strange place in colonial and postcolonial spaces, having been established in 1916 with the purpose of studying the Empire to be able to govern it better. It has gradually become a site of postcolonial discourse that now seeks to decolonise histories of lands, objects, stories and people. Most recently, this debate occupied media attention in the United Kingdom, when students at SOAS asked for “white” philosophers like Plato, Kant and Descartes to be dropped from the university’s syllabi.

Dr Elgood’s course has created a postcolonial, highly international corpus of graduates, who now occupy influential positions in the art world. She plays a nodal role in how Asian art is collected, viewed, perceived and conserved across the globe.

In conversation with Deepika Ahlawat, she shares her views on the subject. Excerpts:

How would you describe the work you do?

I work at SOAS, University of London. I am Course Director of the Postgraduate Diploma in Asian art. I am also a specialist and lecture on Indian temples, sculpture and manuscript painting.

What got you interested in art, particularly, Indian art?

I started with an interest in painted manuscripts. This led me to study Mughal painting and to visit India to study the collections and libraries in the research for PhD. From this exposure to India, I grew to love and be fascinated by the culture and the religious art and architecture. It is rare to find a culture where there is, still, a living relevance of mythology and iconography. There is a unique relationship between figural imagery and ideas in Hindu art. This has fascinated me and made the study infinitely enriching.

What are the opportunities and challenges for Indian art, now and in the near future?

There is a growing interest in contemporary art, which has, in my view, sidetracked the study of the ancient art and architecture of India. It is not only simpler but more commercially viable to trade in contemporary art in modern India. This is disappointing and will prevent the continuance of live craft traditions seen in block printing and other areas of the craft. I hope that India supports its museums as a vital part of its heritage and with respect for its history and cultural identity.

Would you describe art/heritage as a public or private matter?

I think art/heritage has, in the past, been both. It was a matter of intimate royal or court patronage in the context of the Indian rulers; however, it has also been of public concern in the construction and worship of lay devotees in the great temples of India. Art/heritage should continue to act in both a public and private capacity. Its purpose in the past was efficacious with a direct relationship with ritual practice in the context of the temple, and a private intimate art in the Hindu illustrated texts. The idea of art as decorative is a recent phenomenon in interior design or in the public municipal architectural sense.

What is your favourite piece/object from your collections/studies and why?

This is one of the large panels of cave three at Badami in Karnataka. This iconographic programme consists of a number of gigantic scenes showing forms of Vishnu. One of these is an impressive figure of the avatar – Vamana, the dwarf. It shows the full, fleshy rounded forms derived from the early Gupta classical style. The panel reveals a vital group of figures emerging from the rock face. It also tells a story with remarkable attention to detail.

It is full of imminent movement and Vishnu striding forth as the dwarf becomes a giant as his footstep towers above the secular figures beneath him. This sculpture emanates power, not only on a human muscular level, but also can be read for its symbolic iconography. It is done at a time when the figures of the deities are depicted with a degree of realism before the ninth century-eleventh century in North India, when they become stylised and more abstracted.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest