Politics

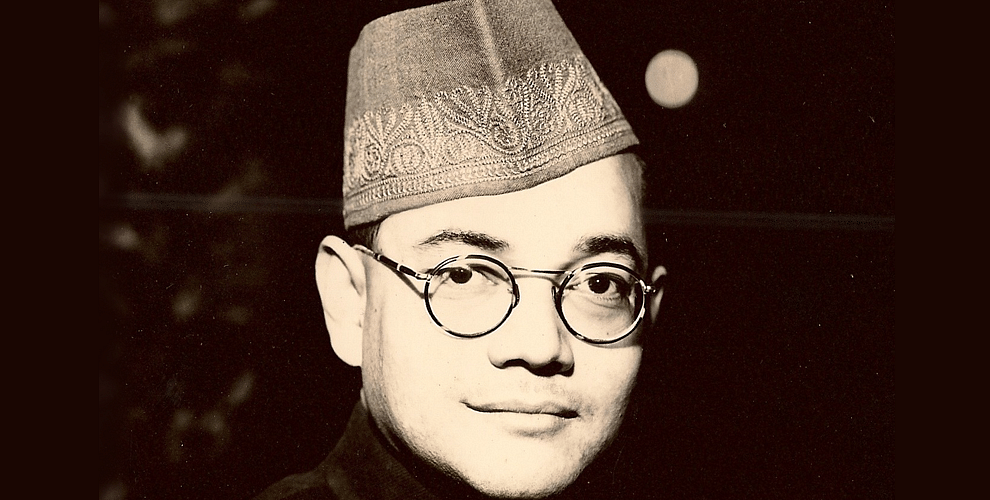

Why can't we know the truth about Netaji's death?

Beginning today, Swarajya will be carrying a series of articles on the mystery surrounding Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose’s death and how successive Indian governments have blocked all attempts to unravel it. We begin with the latest such incident of stonewalling—this time by a government which had promised to reveal the truth.

The office of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has triggered off a storm in both mainstream and social media after it turned down two separate RTI requests of S.C. Agrawal and this writer concerning the secret Subhash Chandra Bose-related files. The development by itself is a good one because commotion is a prerequisite to creating an atmosphere conducive for resolving controversial matters.

There is nothing new in our government’s not wanting to end the mysteries surrounding Netaji’s life and fate. One cannot bring about a closure to a controversy by continuing to sit on over 100 secret files that deal with it. The official narrative, that the Government of India formed two commissions of inquiry and a committee to resolve the Bose ‘death’ mystery, does not take into account the fact that on each occasion the authorities were forced to act under public pressure. Left to them, the statement of Interim Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1946—that Bose had died in Taiwan (the known as Formosa) in August 1945—was gospel.

Hopes of disclosure of the truth regarding Netaji’s fate were raised when, in 1999, the first NDA government instituted the Mukherjee Commission of Inquiry. Then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was not only India’s first truly non-Congress chief political executive, but also someone who openly said that he admired Netaji.

Never mind the present posturing, the Indian National Congress did not even think it fit to have a portrait of Netaji in Parliament House. It was Vajpayee, foreign minister in the Janta Party government, who helped Samar Guha, member of Parliament and close associate of Bose, in his mission. When the portrait was unveiled on 23 January 1978, for Vajpayee it was like the nation had ‘repaid’ its debt to Netaji, albeit “30 years after independence”. The same day he remarked that “historians and scholars should find out why the Congress government had done injustice to Netaji by ignoring him all these years”.

If it wasn’t for Vajpayee, Guha would not have succeeded in 1970 in compelling an unwilling Indira Gandhi government to set up the Khosla Commission of Inquiry—which turned out to be a fraudulent one later on.

When it emerged during the course of inquiry that Indira Gandhi’s government was unwilling to let Justice Kholsa—her father’s friend and her biographer—make an on-the-spot investigation in Taiwan, Vajpayee and 25 other lawmakers wrote to the PM that the commission “should be given facilities to visit Taiwan”.

And so, when the Mukherjee Commission was formed following a Calcutta High Court order, everyone hoped that, with Vajpayee as PM, things would proceed unlike they had under Congress regimes. But as it turned out, the Vajpayee government did not allow Justice Mukherjee to visit Taiwan either, taking a stand that would have pleased Indira Gandhi. The judge eventually visited the country in 2005 after this writer was able to get information from the Taiwan government that there was no evidence of Bose’s death, and passed on the same to the commission.

The Mukherjee Commission report made public in 2006 rapped the government—which for most part meant the one headed by Vajpayee—for putting “a spoke in the wheel of this inquiry”. Both the Prime Minister’s Office and the L.K. Advani-led Ministry of Home Affairs were indicted for not fully cooperating with the inquiry, which concluded that Bose had flown towards the USSR even as fake news of his death was planted.

In any case, in retrospect, one should give credit to the BJP for setting up the Mukherjee Commission. It can be safely hypothesised that had there been a Congress government in place in 1999, there would have been no such chance. In 1986, the Rajiv Gandhi government had ducked a Rajasthan High Court directive regarding the need for an inquiry into Netaji’s mysterious disappearance. With the blatant rejection in 2006 of Justice Mukherjee’s report, the Congress cast itself again as the villain in the story. Lawmakers, including those from the BJP ranks, accused the Congress government of a cover-up in Parliament.

Senior journalist and Rajya Sabha MP Chandan Mitra, for one, said he could not understand why certain Bose files were kept classified in the name of ties with certain friendly foreign nations. Mitra’s newspaper The Pioneer had given constant coverage to the Mukherjee Commission inquiry and had even deputed senior editor Udayan Namboodiri to accompany Justice Mukherjee to Russia.

“Are the friendly countries more important or are the people of India more important?” Mitra asked. “It is not a political question, it is a question of our nationhood.” He predicted that “the people of this country will not rest quiet even if it takes three more generations” to get to the truth about Bose.

In 2012, following the release of this writer’s book India’s Biggest Cover-Up, the demand for declassification of Netaji-related files began making news for the first time. On 9 April 2013, a letter signed by Netaji’s nephew D.N. Bose on behalf of 24 members of the Bose family was handed over to then Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi by Chandra Kumar Bose, the spokesperson for the family. Modi was more than receptive while receiving the letter, and he promised to do something about it.

In August 2013, BJP leaders such as Najma Heptulla, Venkaiah Naidu and Smriti Irani joined Trinamool Congress member Kunal Ghosh in taking the Manmohan Singh government to task in Parliament following its refusal to release some Bose files. There was a media report that on 23 January 2014, Modi had written to Singh that something should be done to settle the mystery. The same day, which was Netaji’s birth anniversary, then BJP chief Rajnath Singh visited Bose’s birthplace in Cuttack and said that “the entire country is impatient to know as to how Netaji died and under what circumstances”. He made a solemn promise that if or when the BJP is in power, the matter would be settled.

This is a backgrounder to the BJP’s present ‘U-turn’ as is being talked about in media and political circles now, even though it manifested a few months ago when both PM Modi’s office and Home Minister Rajnath Singh began toeing the old ‘Congress line’.

Now, the real takeaway that the BJP leaders may not realise at the moment, but will at some point in time, is that the party’s nationalistic image is going to take a big hit if they renege on their promise to settle the Netaji case. Not only that, the BJP now runs the risk of filling the boots of the Congress as the main villain in the story.

There is still time. This writer is hopeful that Prime Minister Modi and the BJP will not want to go down in history as the leader and party which put paid to the decades-old quest to know the truth about the fate of the man but for whom India would not have become free in 1947.

Following Monday’s development when the PMO’s refusal to declassify Netaji-related files was greeted with snide remarks of ‘U-turn’ by the Opposition and dismay by the people who have been following the issue keenly, the author issued a press release. Details are made available below.

Click here to read the press release and the government's response to the RTI application

PMO refuses to place Netaji files RTI query before Narendra Modi

The Prime Minister’s Office has turned down a request to place an RTI query before Prime Minister Narendra Modi which wanted to know whether there is “any information available to the Prime Minister showing that Subhas Chandra Bose was alive or was possibly alive long after his reported death in August 1945”.

“There is no provision under the [RTI] act to place the application before the Hon’ble Prime Minister,” wrote PK Sharma, the Central Public Information Officer (PMO) to applicant Anuj Dhar, a writer and former journalist who’s been attempting to settle the controversy surrounding Netaji’s disappearance.

Dhar also wanted the PMO to “confirm whether or not there are matters so secret that they are known only to the Prime Minister of India. And if yes, within the ambit of such ultra secret matters and records/information related to them, is there any information concerning the survival of Subhas Bose long after his reported death?”

The PMO responded: “As per records, no such information is available.”

Dhar says that the answer is misleading. He says he is sure that “such a class of ultra secret information exists” and only Prime Minister Modi can clear the air on the Netaji issue.

“Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had himself stated in an official statement that certain highly secretive matters are known only to the Prime Minister, who passes the same on to his successor only. How is that the PMO is not aware of that simple fact?” he asks.

Dhar claims that Government of India is fully aware what happened to Netaji and demands that all documents relating to Netaji, especially those from the intelligence agencies, should be put in public domain.

However, the PMO doesn’t seem in favour of the idea. In his application, Dhar cited the numbers of 22 secret PMO files about Netaji and sought their copies. But the office declined to release them saying the disclosure would “prejudicially affect relation with foreign State and also there does not seem any larger public interest in the matter”.

The office hasn’t specified with which “foreign State” India’s relations would sour in case the secret Bose files were declassified.

“The Modi PMO’s stance will do nothing to check the longstanding conspiracy theory that Bose died in Soviet Russia, and that the first Prime Minister of the country had something to do with it,” says Dhar.

“To say that there is no larger public interest in declassification is an affront to not only the Netaji admirers but all those who favour transparency,” says Chandrachur Ghose, who runs a website (www.subhaschandrabose.org) about Netaji. In 2006 Chandrachur and Dhar were informed by the Ministry of Home Affairs during an RTI proceeding that the disclosure of certain Top Secret records relating to Bose’s fate would lead to “law and order problem across the country, especially in West Bengal”.

“We want all Netaji files declassified to settle all controversies,” said Chandra Kumar Bose, the spokesperson for Netaji’s family. Chandra Bose had met Narendra Modi before the general elections with the demand and given a patient hearing.

“Unless India declassifies its own Bose records, it cannot approach the Russians and others for the disclosure of their holdings,” Dhar adds.

The PMO, however, informed Dhar that since 2006 two files concerning Netaji have been declassified and sent to the National Archives.

Dhar’s 2012 book India’s Biggest Cover-Up asserts that the Government knows about Bose’s fate and has kept the people in the dark due to political complications the disclosure would entail.

PMO’S RESPONSE TO DHAR’S RTI APPLICATION

The responses are carried in bold typeface under the relevant questions asked in the RTI application.

To

Shri Syed Ekram Rizwi

Central Public Information Officer

Deputy Secretary, Prime Minister’s Office

South Block, New Delhi – 110011

Subject: Information about the fate/possible survival of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose

Dear Sir

This is an application under the Right to Information Act.

In the spirit of the RTI age, the Prime Minister’s personal commitment to transparency, his admiration for Netaji and the extraordinary nature of the subject matter, I request that this application be placed before the Hon’able PM himself.

PMO response: “There is no provision under the [RTI] act to place the application before the Hon’ble Prime Minister.”

I’d like to have the following information/records:

1. Is there any information available to the Prime Minister showing that Subhas Chandra Bose was alive or was possibly alive long after his reported death in August 1945? If yes, please detail it with supporting records. If the PM is not aware of any such information or records (stored in either the PMO record room or elsewhere—for example the intelligence agencies’ archives), kindly state so categorically.

2. Please confirm whether or not there are matters so secret that they are known only to the Prime Minister of India. And if yes, within the ambit of such ultra secret matters and records/information related to them, is there any information concerning the survival of Subhas Bose long after his reported death?

PMO response for 1 & 2: “As per records, no such information is available.”

3. Please provide photocopies of the following files kept in the PMO record room. Or, allow me an access to these files so that I may select relevant records for photocopying.

2(64) 66-70 PM (Vol VI), 2(381) 60-66 PM, 2(67)/78-PM, 870/11/P/10/93 Pol (Vol 2), 870/11/P/11/95-Pol, 870/11/P/16/92-Pol, 915/11/C/6/96-Pol, 915/11/C/9/99-Pol (Vol 1), T-2(64)/78-PM-NGO, 870/11/P/17/90-Pol, 800/6/C/3/88-Pol, 2/64/86-PM,2/64/86-PM

Annexure: 2/64/78-PM, 2/64/78-PM Annexure, 2(64)/56-66-PM (Vol 1), 2(64)/56-66-PM (Vol 2), 2(64)/56-67-PM (Vol 3), 2(64)/56-68-PM (Vol 4), 2(64)/56-70-PM (Vol 5), G-16(4)/2000-NGO (Vol 1), G-16(4)/2000-NGO (Vol 2)

PMO response: “The information sought is exempted under section 8(1)(a), read with 8(2), of the RTI Act, 2005, as disclosure of the class of information may be prejudicially affect relation with foreign State and also there does not seem any larger public interest in the matter.”

4. In an RTI response to me earlier, (No.RTI/219/2006-PMA, dated 3 November 2006) then Director and CPIO stated that “as regards classified files held by PMO on the subject an exercise is being undertaken to review them for declassification”. I wish to know how many classified files related to Netaji were reviewed under this exercise, how many of them have actually been declassified as a result and sent to the National Archives since 2006.

PMO response: “Two files…have been declassified and sent to NAI.”

If you deny me the information sought in part or full, kindly give cogent reasons for doing so as the information is being sought in public interest over a matter of public importance.

I thank you for your consideration of this application.

Yours sincerely

Sd/ 11 July 2014

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest