Politics

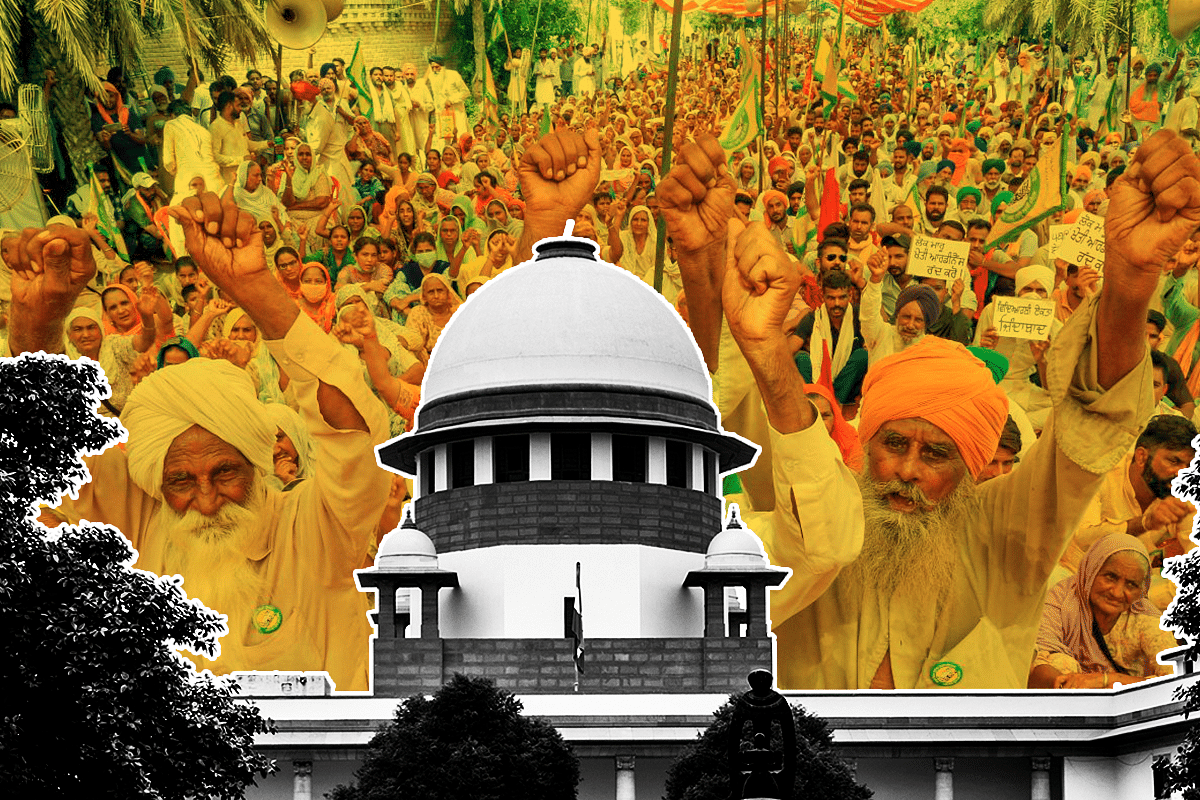

Can Protests Against Agri Reforms Be Allowed To Hijack Economic Policy-Making?

- Should we allow a protest based on spreading fear through lies to stay a law passed by Parliament of India which benefits a large number of our farmers just because of a street veto of a few thousand protesters?

The appropriate role of the judiciary in the farm crisis is important.

There is a lot that can be said — a lot that can be repeated and a lot that can be expressed with regards to the recent developments on the farmer protests.

The long story short is that the judiciary in all its wisdom has noted the inability of the government in dealing with the ongoing protests and it is inclined to stay the implementation of the laws while it forms a committee to address the issues of the farmers.

It has, however, not yet asked the protesters to vacate the borders and put an end to a protest that infringes on the rights of 2 crore citizens of Delhi. These developments pertain to the oral comments made by the bench during the course of today’s (11 January) proceedings — and we still wait for their judgement.

While there is of course politicisation of the issue going on with parties fuelling the protests and trying to milk this as an opportunity to consolidate before the upcoming Punjab elections — the question is whether it is a fair strategy?

Or put differently, should there not be some checks and balances to prevent these events from happening. That is an issue that is best left explored for a later day but the more immediate issues are of appropriate role of the judiciary, the ongoing protests and the way forward.

In a tweet, I had stated that I am, for the first time disappointed with India and its institutions. This disappointment is an outcome of repeated instances of attempts to weaken our democracy.

There is a silent assault underway to ensure that the revealed preferences of the electorate are ignored — that is, the authority of Parliament is systematically being undermined.

The present discourse is alarming as it sets a precedent that any group of people can in future hold Delhi hostage, threaten violence and get whatever they wish either from the executive, legislative or the judiciary.

This is a very dangerous example that we are setting here for various reasons.

For starters, what happens if tomorrow there are protesters demanding that a judicial order be reversed? Will we respond in a similar manner?

Would the honourable court stay and form a committee to look into these issues?

Of course, the two things are not comparable as a law is not necessarily the same as a judicial order. But, the idea that any institutional decision can be subjected to being reversed by brute force or veto on the streets would quickly erode any institutional authority.

There are other concerns too, as the central government too agreed to allow decriminalisation of stubble burning. This shows that the problem is systematic and across all our institutions which are quick to buckle under pressure.

That the protesters are also demanding an extension or perpetuating of a subsidy that is leaving Punjab dry should have made everyone take note of the need to disregard the demand as an illegitimate one — yet the government gave into that demand.

As a consequence, people of Delhi will have to suffer in winters due to air pollution — and yet, the Chief Minister of Delhi, who passed the three ordinances but did a rethink on sensing an opportunity decided to support the protesters and their demand. The Chief Minister of Delhi who was supposed to look after the best interests of the citizens has also decided to ignore us in the hope of gaining ground in Punjab.

Perhaps, there may be alternative policies for dealing with the air pollution fiasco, but the blatant exploitation of ground water of the region is a threat for all — yet we are going to ignore it because the rich entitled farmers are making money at our expense.

Maybe, we should file a PIL and get the court to act — and then wait for farmers to protest against the judgement to see how the situation evolves?

The more pressing issue here is that for 30 years these laws were discussed and debated, they had a degree of political acceptance, yet everyone was quick to politicise the issue in order to thwart its implementation.

Reforms in India are often delayed — but they are inevitable.

Thus, I am confident that farmers of the country will get this reform at some point — but the delay will only blunt its gains.

Consider a situation whereby the 1991 reforms were also stalled — that is a catastrophic scenario to imagine. The new laws are an equivalent of those very same reforms. This should give us an idea of the importance of these reforms — which have been recommended by experts across the board with genuine scholarship in several committees.

The more important point here is with regards to economic policymaking in the country and why it must be restricted to either the executive or the legislative. The main thing about economic policymaking is its redistribution impact. That is, economic policymaking tends to affect economic growth, prosperity and the distribution of the dividends of the same among people.

The very basic question in economics is what to produce, how to produce and for whom to produce —the answer to which have to be determined by government policies.

These policies must inherently factor in the aggregate preferences — or the revealed preferences of the society in general.

Reforms, especially economic reforms tend to have significant distributional impact and thus, revealed preferences as an outcome of electoral results become significant to signal our policymakers on the policy with maximum possible acceptability.

It is also a question of technocratic expertise blending with public accountability which must govern these issues. A good example is monetary policy or taxation policies which are important policies that weigh in conflicting interests which are resolved by these institutions.

In the present case of farmers, there are two conflicting interests — farmers who support the laws and farmers who are protesting. The number of farmers who support the new laws are greater than those who are protesting from what we know so far.

The question that thus arises is that should we allow a protest based on spreading fear through lies to stay a law passed by Parliament of India which benefits a large number of our farmers just because of a street veto of a few thousand protesters?

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest