Politics

Captain To Channi: What On Earth Is The Congress Doing In Punjab?

- Congress' struggles with power transition, from Sonia Gandhi's generation to Rahul Gandhi's, are not new.

- Desperate to start a new inning in Punjab, the Congress may have ushered its irreversible end.

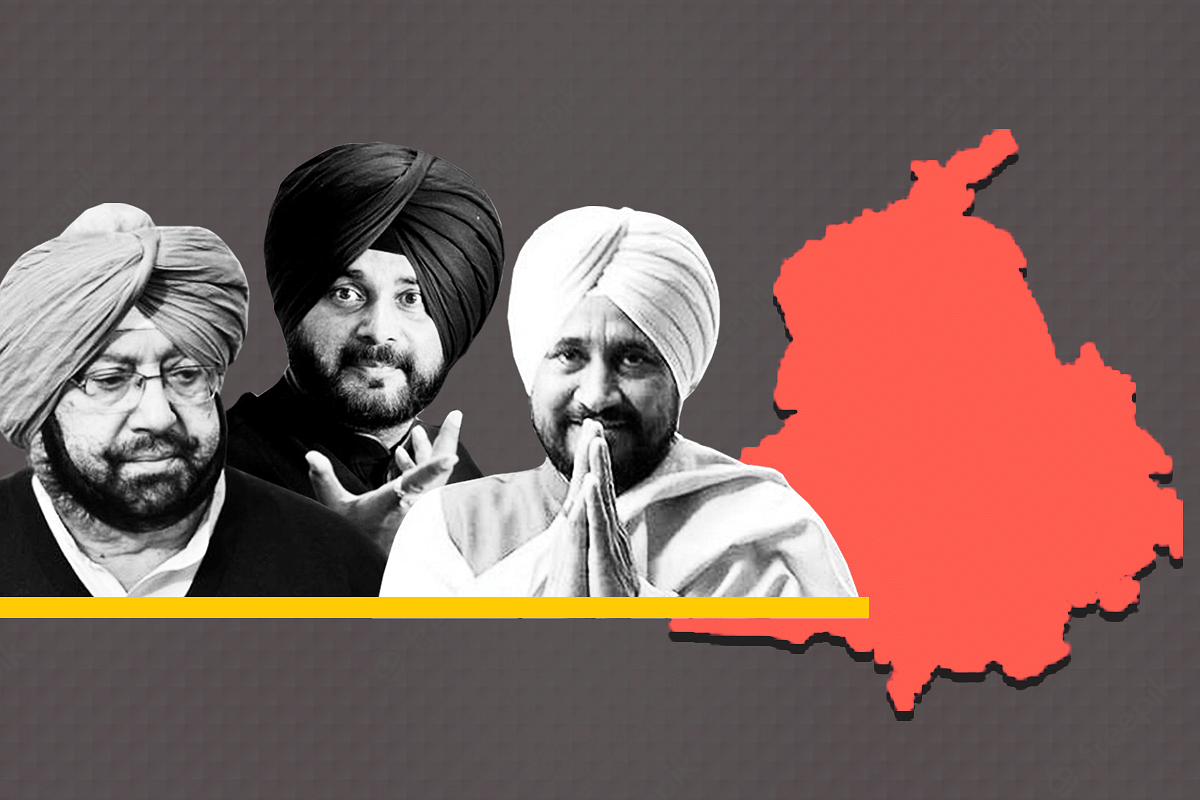

Captain Amarinder Singh (left), Navjot Singh Sidhu (centre) and Charanjit Singh Channi (right)

Picture this; the final day of a Test Match. The batting team, Congress in this case, did everything right, and now requires only 80-odd runs in the final two sessions of the day, on a surface that has absolutely nothing for the bowling attack made up of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD).

With all the ten wickets in hand, the Captain of the Congress is leading from the front on a wicket as dry and dead as the Sahara Desert, and then it all goes haywire.

Team-mates are running each other out. Batsmen are gifting their wickets by either handling the ball or decimating their stumps with the bat, and while the bowlers are stumped with shock, the bowling team can only wonder as to what the Congress is really thinking.

Eventually, the team loses nine wickets in the span of one session, and has the final pair on the crease, a reckless power hitter in Navjot Singh Sidhu, who is without the temperament of surviving the final session, and an unknown tailender in Charanjit Singh Channi. The bowlers smell blood while the Captain of the batting team, distraught, is nowhere near the pavilion.

There is no better cricketing analogy to describe the self-destructive pursuit Congress has opted for in Punjab.

All the party had to do was wait for six-odd months, wait for the election campaign to begin, get Sidhu and Captain Amarinder Singh (CAS) together in what would have been an engineered yet imminent and indispensable power transition. The election was anyway in the Congress' bag, given the way the farmer protests had played out, and all they had to do was plead before the farmers in a few rallies, and the job would have been done.

Yet, Rahul Gandhi woke up and opted for chaos, to put it in the language of the meme universe.

It would be incorrect to draw similarities between the events of Punjab and Gujarat, where Vijay Rupani made way for Bhupendra Patel only a few days ago. What we saw in the BJP-ruled state was a power transition, in the works for months, timed 15-months ahead of the state assembly elections, and with political significance and benefits for the ruling party in the state. The outgoing CM felt humbled and committed to the party at the end of it.

What we saw in the Congress-ruled state of Punjab, however, was a political coup, in the works for months through Sidhu and the blessings of 10 Janpath, untimely with the state going to polls merely 6-months from now, and with political consequences for Congress who chose to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. At the end of it, the outgoing CM felt humiliated and unsure of continuing with the party.

Congress' struggles with power transition, from Sonia Gandhi's generation to Rahul Gandhi's, are not new.

The incapacity to engineer a transition cost them dearly in Madhya Pradesh, puts them in the news each day in Rajasthan, will put them in the news in Gujarat soon, and has resulted in many high-profile exits in several states in the last few months.

However, the blame here also lies with CAS, who in a desperate attempt to please the party high command, ended up eroding his entire legacy, and was left without the seat and support. Singh, aligning himself with the party rather foolishly, protested against the farm laws, similar to what his government had ushered with great success before 2007 or advocated for in the state economic survey of 2019.

On the issue of Article 370, he toed the party line. In January 2020, CAS stated that the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019 was against the secular fabric of the country and went on to compare it with the ethnic and religious cleansing of Hitler's Germany.

Toeing the Congress party line, CAS ignored the sufferings of Sikhs in Afghanistan and Pakistan and Hindus in Bangladesh and compared Modi's India to Hitler's Germany, calling people to speak against what he perceived as an unprecedented atrocity.

For Singh, the political defeat at the dusk of his career shall hurt, for he could be denied a respectable retirement, and irrespective of his decades of service to the state, would be remembered as the Chief Minister who was dismissed by the Gandhis sitting in Delhi. Not a pretty sight at all.

He has already made a public spectacle of his retirement, opting not to go out without a fight. From here, the Captain can either create his party, and eat into the Congress vote share. At the age of 80, political retirement is imminent, but could CAS take a leaf out of Prakash Singh Badal's book who started a ten-year tenure as the CM back in 2007 at the age of 80, assuming he has some MLAs to begin with, for the two dozen MLAs he has been claiming the support of are nowhere to be found, yet.

The BJP door would always be open, and would make for great optics as well, but given the last few months of the farmer protests, the inclusion of CAS within the BJP may irk the voters to a larger extent. For CAS, the ideal option would be to float his party and play the kingmaker, for a five-way contest in Punjab could lead to a hung assembly, but then who would he side with for AAP and the Akalis are non-starters, Sidhu is out of the question, and thus, the BJP?

The bowlers here would also be doing all they can to pick up the last wicket. AAP, to begin with, is winning the perception battle. While many claim the emergence of the AAP as the clear winner six months from now, one wonders what the party has done on the ground to go from a laughing stock with a handful of MLAs and a single MP in the state in 2019 to being the political dark horse in 2022.

With Congress fielding a Dalit-Sikh Chief Minister and two deputies as per the rumours, including a Hindu, the idea would be to capture the Dalit-Sikh vote bank, constituting more than 30 per cent of the population in the state. However, unlike other states, Dalit-Sikhs in Punjab do not vote in unison, and thus, the temporary elevation of Channi, a scapegoat to shield Sidhu from the impact of Captain's public departure, may not yield the results the party is hoping for.

The Akalis, however, relatively are in a far better position than they were six months ago, for they could now, like the Congress, play the caste card, build upon the political debris of the Congress, and capture the Jat-Sikh vote that had been critical to their victories in 2007 and 2012.

Even in their defeat in 2017, the Akalis, aligned with the BJP, had the greatest vote share amongst Jat-Sikhs, but now would be the opportunity to pull it back from AAP, another party that has promised a Dalit-Sikh CM, and the Congress.

BJP, to begin with, needs to find faces who are willing to face the heat in the face of angry farmers. Even though staged and scripted, the protests have dented the party's prospects in the state for at least another five years. However, fortunes of the party could reverse overnight if the Captain comes clean on farmer protests, but that's a bit far-fetched for now.

For the Congress, this is a new beginning in Punjab, sans Captain Amarinder Singh, who operated without the interference of 10 Janpath and without the political baggage of the events of the early 1980s that concluded with the slaughter of Sikhs in Delhi in 1984 after the murder of then prime minister Indira Gandhi.

Even during most election campaigns, it was Singh who ran the show, with occasional appearances from the Gandhis.

He did not disappoint the party leadership too, winning majority seats in the state in the face of a BJP wave in 2014 and 2019. Yet, a CM who won the state for the party in the face of the unstoppable Modi wave, twice, was fired by a Congress leader who lost the nation, twice, in the same wave.

For Gandhis, the imminent trouble lies in Newton's Third Law of Motion, and while it is too early to speculate what the Captain might be upto, the elevation of Channi to shield Sidhu is an indicator of the threat the Congress senses. The other stakeholders, meanwhile, can sit back and enjoy the struggles of the last wicket.

Desperate to start a new inning in Punjab, the Congress may have ushered its irreversible end, for this Patiala Peg could end up looking too strong for the Gandhis.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest