Politics

Did The BJP Win 'Gujarat 2022' In 2021 Itself?

- There are three factors at work–a groundswell, their organisational structure on the ground, and a few star campaigners–that can lead to sweeping victory for the BJP in Gujarat in December 2022.

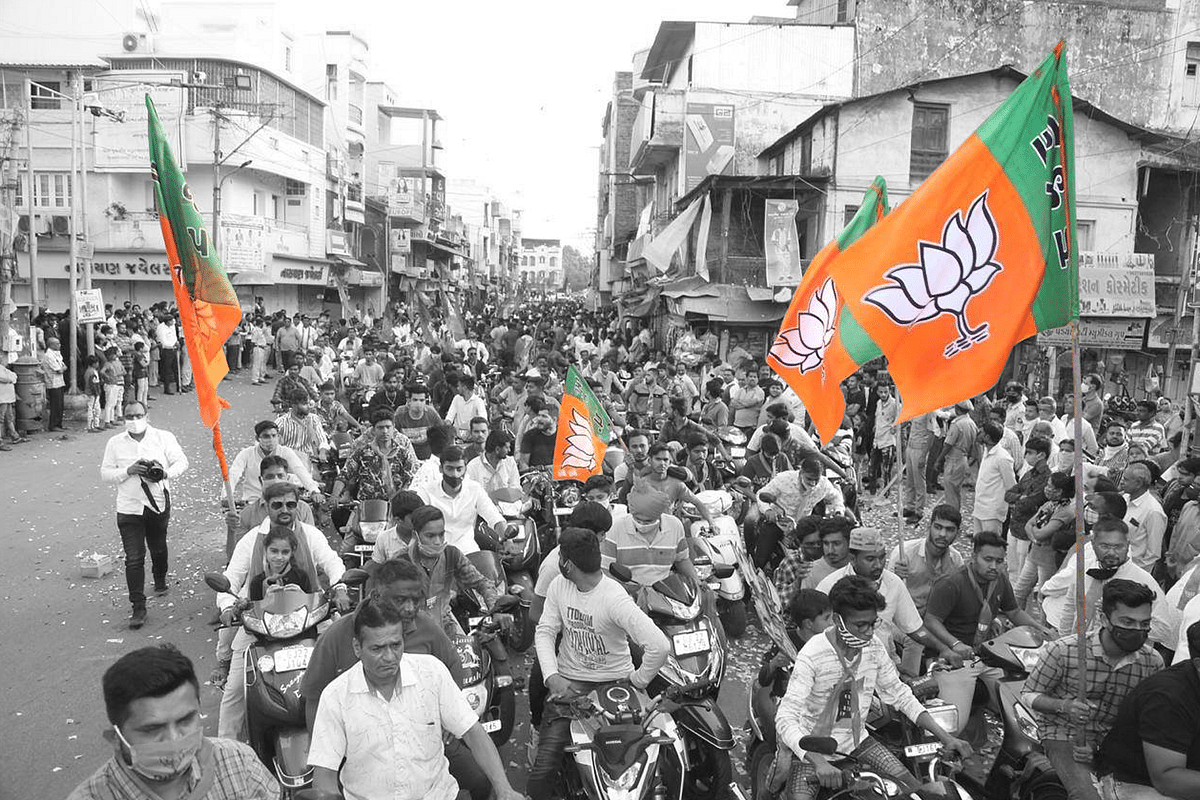

The BJP workers celebrating the election victory.

Once in a rare while, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) pulls out all the stops to show the opposition just how overwhelming its electoral machinery can be.

We saw this in the Madhya Pradesh assembly elections of 1990; Gujarat, 2002; Rajasthan, 2013; Uttar Pradesh, in the 2014 parliamentary elections; Karnataka, in 2019; and then in the Uttar Pradesh assembly elections of March 2022.

On such occasions, three factors come together to create a multiplier effect – a groundswell, their organisational structure on the ground, and a few star campaigners.

It appears that the BJP is gearing up for precisely such a showing in Gujarat this year. The relentless, unsparing way in which the BJP has reversed the gains the Congress made in the 2017 assembly elections augurs well for a possible, unprecedented sweep by the BJP in December 2022.

Why do we say this?

In 2017, the BJP was surprised by a triple caste card which the Congress played. This was the infamous ploy to split the Patidar, Other Backward Class (OBC) and Dalit votes using, respectively, Hardik Patel, Alpesh Thakor, and Jignesh Mewani (see here for a detailed analysis).

As a result, although the BJP retained the popular mandate, and even improved its vote share from 2012, it lost 33 hard-won seats to the Congress, mainly in Saurashtra, North Gujarat, and the tribal belt.

But since then, the BJP has steadfastly striven to undo those reverses, and the results are clearly showing. This strategy has three parts.

In the first instance, Alpesh Thakor was enticed to resign as an MLA to join the BJP, and promptly side-lined after he lost his byelection.

Jignesh Mewani was exposed as a radical with Marxist, Ambedkarite inclinations following his involvement in the 2018 Bhima-Koregaon case, in Maharashtra, where violence led to the death of a youngster.

That labelling as an ‘Urban Naxal’ left Mewani with little choice but to join the Congress (not least because there is no Communism in Gujarat); and that, in turn, led to the loss of his distinct identity.

Next, a series of defections from the Congress were engineered in 2020. The BJP won most of the byelections. This was a smart move, since the targets were mainly in Saurashtra and the tribal belt.

And finally, Bhupendra Patel was made Chief Minister, Hardik Patel was inveigled into joining the BJP in June 2022, and Deputy Chief Minister Nitin Patel chose to retire from active politics.

This took the wind out of the Patidar agitation’s sails, and the Patel community is once again united behind the BJP.

Along with this, the BJP has also recently contrived a fresh spate of defections from the Congress – again, mainly in Saurashtra and the tribal belt.

Importantly, many of these seats were Congress holds in 2017, meaning that they won these in 2012 as well, in the face of yet another Modi wave. So, it is evident that the BJP is seeking to reverse Congress gains made in 2017, while expanding into Congress strongholds.

How does this strategy translate into seats, and on the ground?

A table of seats in the legislature shows that the BJP had recouped half its losses by 2021 already.

In addition to this, the Congress has suffered 20 defections to the BJP since the last assembly elections. Many were in 2020, and the rest, during the course of this year.

The BJP has also wrested a tribal seat from an independent after he was disqualified (125-Morva Hadaf).

Pertinently, seven of these seats are reserved for tribals. Of the 27 tribal seats in the state, the Congress won 16 in 2012, the BJP 10, and ‘Others’ one.

In 2017, the BJP’s tally went down to nine (in spite of two gains), the Congress held at 15 (two gains), and the ‘Others’ went up to three (two gains).

That is why these defections become important in the current context, because it is quite possible now, that the BJP may register its best ever showing in the tribal belt next month.

The BJP is adopting a similar approach in the 13 seats reserved for scheduled castes. In 2012, it won 10, with the Congress bagging the balance three.

In 2017, the Jignesh Mewani factor (along with other factors) brought the BJP’s tally down to seven, with the Congress winning six (four gains, one of which was Mewani, who contested as an independent).

As on date, the BJP has already won back one of these (106-Gadhada), and is on track to win back more.

(Note: the number of defections from the Congress to the BJP will not tally with the number of additional seats gained by the BJP between 2017 and 2021, nor with those lost by the Congress in this period, because some Congress defectors (like Alpesh Thakor) lost their byelections.)

For their part, the BJP has suffered only one defection as on date: the sitting MLA for Matar seat resigned to join the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) after he was denied a ticket. He will lose. And that is pretty much the case for the bulk of the AAP candidates as well.

While the party created a flutter in the media during September and October, it has no extensive organisational structure on the ground, there are no solid indications that it has replaced the Congress in rural areas, and its campaign machinery is not visible on the ground in the cities.

This writer is yet to spot a single AAP worker in western Ahmedabad, standing at street corners handing out flyers. Their candidates have yet to conduct road shows, and no candidate has turned up for door-to-door campaigning.

That is incongruous, since the party is usually ‘in-your-face’ during election time. This lack of a visible presence thus puts prepoll surveys giving the AAP over 20 per cent of the vote share in strong doubt.

On the other hand, the Congress can be heard, and seen. Party workers have been spotted occasionally, milling near public parks or polling booths, as they go about their work.

Consequently, a qualitative, representative assessment is that the Congress will not do as badly as surveys predict (at least on vote shares, because if the AAP cuts their votes, the Congress seat tally will drop like a stone); and the AAP will not do as well as the surveys would have us believe.

It is in this backdrop that Narendra Modi embarks on a hectic three-day campaign across the state this weekend. He is scheduled to conduct a number of rallies, where he will also speak in Gujarati.

This is important because thus far during the campaign, he has restricted his communication to Hindi; and for those who don’t know the state, locals only cheer when the Prime Minister speaks in Hindi, but when he addresses them in Gujarati, they roar!

These are the three factors at work – a revitalised BJP striving to make up for their minor hiccup in 2017, a groundswell of fresh support, and a star campaigner who can pull the vote like no one else.

And it is for these reasons that one could say, that the BJP already won the 2022 elections in 2021. What happens next will most probably be an unprecedented sweep.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest