Politics

The Likely Outcome Of 'Gujarat 2022', Like The State's Politics Of Last Three Decades, Can Be Traced Back To Advani's Rath Yatra

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Jul 14, 2022, 01:43 PM | Updated 01:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

It was October 1990. Lal Krishna Advani, president of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was blazing a trail across much of India with his rath yatra, under the adroit management of a young party functionary named Narendra Modi.

The objective of the yatra was potently symbolic — the construction of a grand temple at the birthplace of Lord Rama in Ayodhya, atop which Mughal emperor Babur’s mosque stood in lingering agony.

By this yatra, the BJP sought to force the populace above divides of religion and caste which had manacled the subcontinent in decrepitude for so long. It was a moment of awakening which the nation had not witnessed since the freedom struggle half a century earlier. Everywhere, crowds gathered in droves to hear Advani explain how terms like secularism and appeasement had infested our body politic so acutely, that the time to reclaim our civilisational roots was now, or never.

In New Delhi, prime minister V P Singh watched anxiously as the yatra rolled on. While he had successfully ousted prime minister Rajiv Gandhi and the Congress party in the general elections of late 1989, over the Bofors scam, Singh had won, and managed to cobble together a rickety coalition, largely because of the vital support he received from the BJP. And now, it looked like Advani and the rath yatra would sweep Singh aside. As Jay Dubashi writes in The Road to Ayodhya, it was common knowledge in high circles, that V P Singh was finished the day Advani started his yatra from Somnath on 25 September 1990.

In desperation, Singh finally ordered Bihar chief minister Laloo Prasad Yadav to halt the yatra, and Advani was arrested at Samastipur on 23 October. The BJP promptly withdrew its support to V P Singh’s Janata Dal-led (JD) coalition, the government lost its numbers, and the prime minister was forced to resign a few weeks later.

In the tumult, very few realised and fewer still remember that Advani’s epochal arrest set in motion a series of political events in Gujarat, which still reverberate in that state today — and which will, in their own way, manifest themselves in the assembly elections scheduled for later this year.

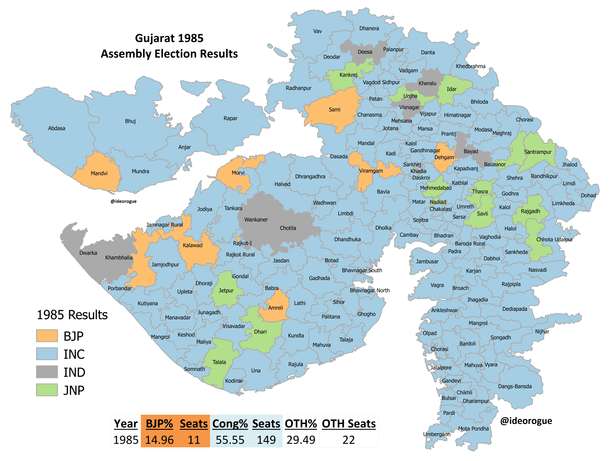

The Congress party, which had won massive mandates in Gujarat for the first four decades after independence, was nearly wiped out in the assembly elections of March 1990. Here are the results:

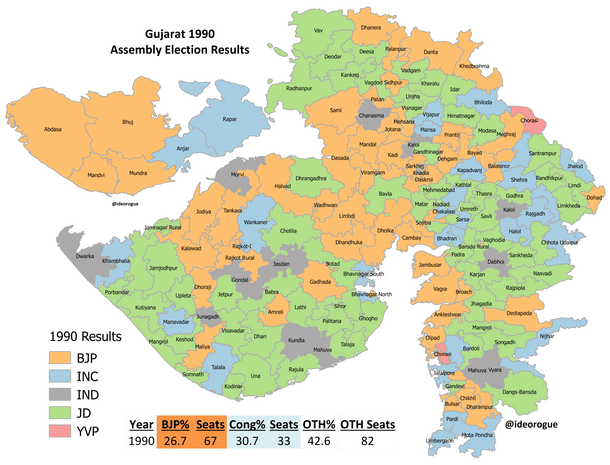

From 155 seats and 56 per cent of the vote share in 1985, the Congress plummeted to just 33 seats in 1990. Although there had been no formal pre-poll alliance, the BJP joined hands with the JD since they were already allies at the Centre in the VP Singh government. Chimanbhai Patel of the JD became chief minister, and Keshubhai Patel of the BJP was deputy chief minister.

It was the BJP’s first big surge in a large state since the party was formed in 1980. It was also sweet revenge for Chimanbhai, who had been with the Congress, and chief minister of Gujarat till 1974, when the Navnirman movement forced him out of office, and eventually triggered the Emergency.

Chimanbhai’s primary bete noire in the 1990 assembly elections (he had a long list) was Madhav Singh Solanki of the Congress, who won two provincial elections with thumping majorities in 1980 and 1985. Solanki’s formula was called KHAM — rank vote banking using ‘Kshatryias, Harijans, Adivasis and Muslims’, and it worked brilliantly for the Congress.

The scale of Solanki’s 1985 win is self-evident in the map below:

But in 1990, Chimanbhai developed a successful counter formula called ‘KOKAM’ (‘Koli, Kanbi and Muslims’), by bringing together the Koli OBC community which amounts to a fourth of the state’s population, various agrarian communities collectively known as Kanbis, and Muslims. The fact that the vote was split three ways, between the JD, the BJP, and Congress, also aided him in using KOKAM to counter KHAM. The results of the 1990 assembly elections are given in a map below:

Through all this, the BJP continued ploughing its lonely furrow. But Advani’s arrest and the BJP’s decision to withdraw support to VP Singh’s JD government, meant that they also had to withdraw their support to Chimanbhai Patel’s JD government in Gujarat. This, they did.

In desperation, Chimanbhai instantly junked his ancient animosities and allied with the Congress — first as a coalition partner, and then more materially, by merging the state JD unit with the Congress.

This was a turning point for the BJP, who now realised that the only way they could fully overcome the old game of playing caste against caste, was by consolidating their base and expanding it, on an unapologetic Hindutva plank. It worked; not least since incensed voters never forgave Chimanbhai for his betrayal, and also because he died in office, in 1994.

Over the next five years, the BJP worked the grassroots like a party possessed, to win the state in style in 1995. And, while they did have a hiccup in 1996-1998, thanks to a rebellion by Shankar Singh Vaghela, who split the party and joined the Congress, they have since maintained a position of electoral omnipotence in Gujarat for a full quarter century now.

Yet in 2017, just when people were lulled into thinking that caste and religious politics was a thing of the past in Gujarat, vote banking reared its ugly head once again; after Solanki’s ‘KHAM’, and Chimanbhai’s ‘KOKAM’, came Rahul Gandhi’s ‘hokum’.

Gandhi deployed three firebrand community leaders to break the BJP’s assiduously-constructed supra-caste consolidation: Jignesh Mewani, a Dalit, Alpesh Thakore, an OBC, and Hardik Patel, a Patidar. Consequently, 2017 was the most intemperate poll Gujarat had seen in ages (elections in the state usually tend to be relatively civil affairs, with election rallies often exuding a carnival feel).

The unconscionable ploy nearly worked, because the one thing the BJP does not know how to play is the caste game; it is a structural flaw which the Congress identified, and tried to take advantage of in the worst possible way, especially in the rural areas.

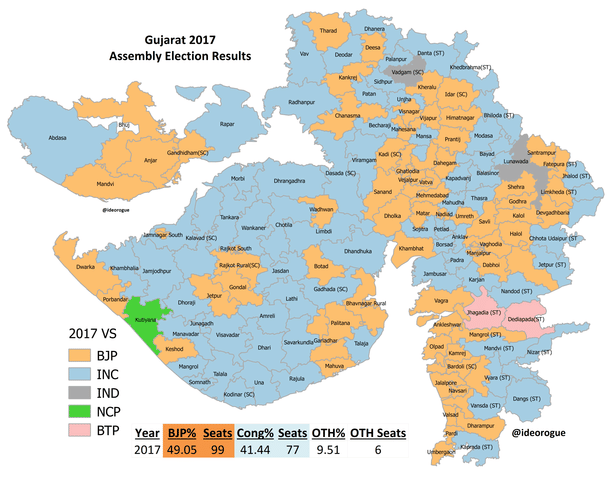

The BJP’s seat tally fell to double digits for the first time since 1995, and as a map below shows, they lost a number of seats to the Congress in their traditional bastions of Saurashtra and north Gujarat.

In one sense, though, it is good that Rahul Gandhi followed a divisive approach in the 2017 assembly elections, because it woke everyone up to the perils of identity politics, and prevented the BJP from becoming effete. Decades of an overwhelming majority, and a content electorate, can do more damage to the best of parties than a rebellion can.

As a result, the BJP pulled up its socks, went through a trying, but necessary period of leadership changes (to somehow fill the yawning void left behind by Narendra Modi), and serially neutralised the mayhem set in motion by the Congress in 2017. Today, Hardik Patel and Alpesh Thakore are with the BJP, and Jignesh Mewani is formally and finally with the Congress (after having publicly, and repeatedly, demonstrated that his heart and mind are more in tune with the militant Maoism of urban naxals, than any mainstream political party or ideology).

Consequently, the Congress now enters the run-up to the December 2022 Gujarat Assembly elections without a strategy, without a popular leader of stature, and with the Aam Aadmi Party snapping at their heels; to the extent that the Congress’s old guard in the state, like Arjun Modhwadia, Bharat Singh Solanki, or Shaktisinh Gohil, have not shown much enthusiasm to lead the charge, and are hardly ever in the news.

On the other hand, the BJP has repaired its inter-community equations and power-sharing dynamics, reorganised its state leadership, and successfully thwarted those divisive forces which, admittedly, gave them quite a scare in 2017.

In conclusion, then, and even before the first surveys are run, a qualitative assessment of the political situation in Gujarat, is that the BJP will do far better than it did in 2017, and quite probably improve upon the stellar mandates it received in 2002, 2007 and 2012. The reason is that enough people in Gujarat, decades after events set in motion by Lal Krishna Advani’s arrest in 1990, have realised the perils of identity politics once again.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.