Economy

Why Do All Investments Go To 'X' State: Here's Why!

Urvashi A and Neeti C

Jul 15, 2025, 11:59 AM | Updated 11:59 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The news headlines often paint a simplified picture of India's economic progress: 'X state gains an investment, Y state loses one.'

But when a single state like Gujarat consistently attracts a lion's share of the pie, the political chorus grows louder, with the INDI Alliance quick to allege bias and "diversion" orchestrated from the top.

But does capital really move like a centrally controlled water tap, opened here, closed there?

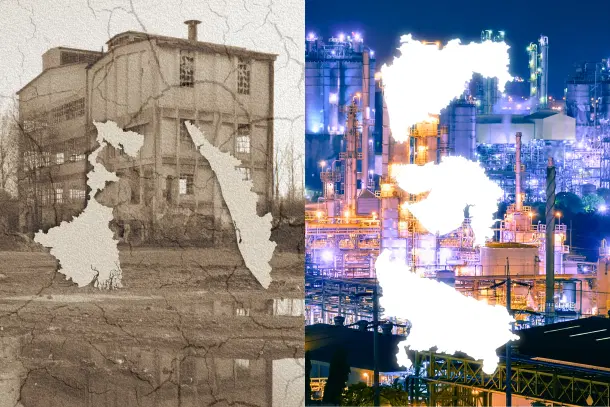

The Self-Inflicted Wounds: Lessons from States like West Bengal, Karnataka, and Kerala

While everyone focuses on where the investments are going, they often ignore the more important question, why they are going there in the first place.

The truth, less convenient for some political narratives, is that capital is not blindly obedient to power. Infrastructure, policy clarity, land acquisition speed, red tape (or the lack of it), these are the real forces that quietly pull in investors or push them away.

Gujarat’s investment story may be consistent, but it is no accident. It is the outcome of years of strategic industrial policy and not divine intervention from Delhi.

Contrast this with West Bengal, which issued most of its policies between 1993 and 2021 through government notifications, not statutes. This distinction mattered, since statutes are formal laws passed by the legislature with strong legal enforceability, while notifications are executive instruments with limited legal backing.

As a result, companies had limited legal recourse if the government failed to deliver on its promises. Combined with militant trade unionism, weak enforcement of industrial peace, and chronic infrastructure gaps, the message was clear: West Bengal was a high-risk territory.

The result? A mass corporate exit. A total of 2,277 companies, including 39 listed firms, shifted out of the state between 2019 and 2024.

The TATA Singur fiasco was an early warning. Industry fled to Gujarat, where investor terms were clear and reliable, while West Bengal’s farmers gained nothing from the political grandstanding of Mamata Banerjee. No industry, no welfare.

The tipping point came in April 2025 with the Revocation Act, which retroactively scrapped all industrial incentives from the past three decades. This sent a signal that West Bengal no longer honoured its word. Yet despite the collapse of investor trust and flight of capital, the Trinamool-led government continues to scapegoat the Centre.

Similarly, Kerala’s industrial stagnation is not incidental. It is structurally engineered by decades of policy choices that prioritise control over competitiveness.

The Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963, placed severe ceilings on landholdings, effectively making it near-impossible for large industries to acquire contiguous land parcels. The problem was compounded by the Kerala Conservation of Paddy Land and Wetland Act and a decentralised planning system that gives industrial approval power to local bodies, which are often averse to large-scale development.

These frameworks, driven by a control-heavy Left political ethos, have discouraged private investment and stunted industrial scale. In 2023–24, manufacturing made up only 12.6% of Kerala’s Gross State Value Added (GSVA), among the lowest in the country, signalling chronic underperformance.

Further, the closure of legacy industries like coir, cashew, and textiles speaks of a deeper malaise like militant labour politics and bureaucratic overreach, which Kerala was clearly not able to fight.

Another stark example of self-sabotage is the decline of Uttar Pradesh under the so-called “Gunda Raj,” particularly during the mid-2000s, with 2006 marking a visible low point.

While other states like Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu were rolling out red carpets for industries, Uttar Pradesh was actively pulling the rug from under its own.

Kanpur, once hailed as the “Manchester of the East” and home to over 3,000 industries, was reduced to an industrial graveyard. During this period, high-revenue sectors like leather, paan masala, hosiery, soaps, and textiles, which collectively generated thousands of crores annually, steadily collapsed.

The textile industry shifted base to Gujarat and Coimbatore, not due to market forces but because Kanpur’s roads were so dilapidated that transporting goods became a logistical nightmare. Flour and pulses mills moved operations to Madhya Pradesh, citing chronic power shortages.

In fact, in 2010, Kanpur Industrial Development Corporation (KIDC) members noted that Kanpur was home to major industrial players like LML, Tata Motors, JK Group, and British India Corporation. But under the Bahujan Samaj Party and Samajwadi Party’s regime, all of them shut down operations, blaming policy flip-flops and poor infrastructure.

The decline was not just economic, it was institutional.

Fast forward to 2025, Kanpur is once again preparing to reclaim its position as an industrial hub, with the state government announcing plans to develop a dedicated footwear industrial park.

Not only this, poor policy decisions can undermine even those states that have built a strong industrial base, Karnataka being a prime example.

The Congress-led government increased distillery licence fees by 50%, taking the annual cost for companies like Huli Spirits from ₹63.10 lakh to ₹90 lakh. Founder Aruna Urs publicly called it “pure extortion.”

Despite reaching out to the state government, he received no response, and was later approached within 24 hours by Andhra Pradesh Minister Nara Lokesh, who offered a “tailor-made excise policy.”

Instances of corruption, such as bribe demands ranging from ₹30–70 lakh for CL-7 licences (liquor licences), have further tarnished the state’s business climate, risking its long-standing reputation as a manufacturing and investment hub.

In January 2025, while states like Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh were attracting investments from global investors at the World Economic Forum in Davos, CM Siddharamaiah chose to stay back, citing “personal engagements.”

Karnataka, under his leadership, opted out of the world’s premier investment platform and instead hosted its own Global Investors Meet, boasting MoUs worth ₹6.57 lakh crore. But behind these glossy headlines lies the fact that most of these deals are yet to move an inch on the ground.

Is Gujarat Winning, or Are Pro-Investment States Simply Playing Smarter?

The narrative that all investment is being "diverted" to Gujarat from other states is factually incorrect and baseless.

Maharashtra, not Gujarat, has consistently led the country in attracting FDI, accounting for 31% of India’s total FDI equity inflows. Gujarat, while among the top receivers of FDI, shares that space with other high-performing states like Haryana, Tamil Nadu, and Delhi.

Policy clarity, administrative efficiency, and a genuine commitment to enabling business have helped them secure investments.

In contrast, states that resort to blame games and scapegoating political figures for their economic stagnation often have little to show in terms of concrete reform or investor confidence.

Gujarat’s industrial strategy is not just about big promises. It is built on a clear and well-structured policy framework.

The Gujarat Industrial Policy 2020 established the Single Window Facilitation Committee (SWFC) and District Level Facilitation Committees (DLFC), backed by the Investor Facilitation Agency (IFA) and dedicated relationship managers for investors. These mechanisms allow for integrated applications and time-bound approvals, reducing red tape.

The state also offers up to 25% subsidy (up to ₹30 crore) for developing private industrial parks, along with targeted tax incentives and support for sustainable practices like green tech and cleaner production.

Maharashtra, too, is not resting on legacy.

Its Make in Maharashtra and 2019 Industrial Policy offer capital subsidies, stamp duty exemptions, electricity duty waivers, and a single-window approval system through the MAITRI portal. The Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) creates industrial zones with plug-and-play infrastructure, and the state incentivises development in backward regions like Vidarbha and Marathwada to ensure balanced growth.

These are not token gestures. They are systemic efforts to build a business-ready environment.

From Red Zones to Growth Zones: How Reforming States Are Outpacing the Rhetoric

Take Chhattisgarh, for instance. Once known primarily for Maoist violence, the state has rewritten its story with a ₹4.5 lakh crore investment wave within just six months of its new industrial policy, nearly matching its entire GSDP.

This transformation is not due to the blessing of a single party, but the result of bold political clarity and focused execution, including 350 process reforms, land offered at token rates (such as BEML’s 100-acre allotment at ₹1 per acre), and a shift from vague MoUs to concrete “Invitations to Invest.”

Chhattisgarh is now home to India’s first Gallium Nitride semiconductor fabrication facility along with AI-powered data parks, proving that when governance aligns with intent, even a Maoist stronghold can turn into a manufacturing magnet.

Similarly, states like Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Goa have also witnessed remarkable industrial growth by prioritising long-term development over short-term political optics.

Under the new government, Andhra Pradesh has, in fact, secured investment proposals worth over ₹9.4 lakh crore in the past year, driven by its investor-friendly policies.

These states are showing that decisive governance, bold reforms, and a clear focus on fiscal sustainability can yield far more than vote-bank politics ever will.

It is not that every Indian state has always tapped into its full industrial potential, but the real difference today is who is choosing reform over rhetoric.

While some continue to shift blame outward, others are rolling up their sleeves and getting to work.

Urvashi A is a political observer and a budding lawyer. Neeti C is an independent political researcher from Presidency University (Kolkata).