Economy

Insolvency And Bankruptcy Code Cannot Deliver If Courts Won’t Let It

Deepesh Gulgulia

Jul 15, 2025, 01:05 PM | Updated 03:05 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In 2016, India introduced the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code to overhaul how the country dealt with business failures. It promised a time-bound, predictable path to resolution. Struggling companies would either find new life or be shut down quickly, allowing money, assets and workers to return to productive use.

For the first few years, the law was delivered. Banks recovered more, projects restarted, and the process inspired confidence. This piece focuses solely on the IBC, not all special laws, as a case study of how judicial processes and legislative design can derail even the most ambitious economic reforms.

But today, the IBC’s core promise is under threat. Not because the law is flawed, but because its implementation is slow and increasingly reversible. Cases that should have ended years ago keep getting dragged back into courtrooms. Investors hesitate, banks hold back, and the economy loses momentum without anyone noticing.

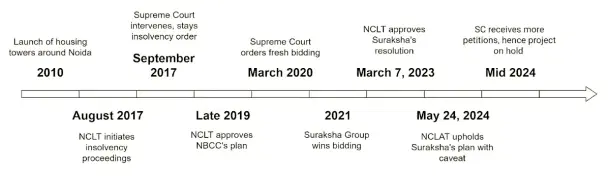

Few stories show this breakdown more clearly than Jaypee Infratech, a real estate developer that once promised homes to over 22,000 families near Delhi. When the company collapsed in 2017, buyers were left in limbo, with towers half-built and life savings stuck.

After years of legal battles, a resolution plan was finally approved in March 2023. But more than a year later, construction has still not resumed. Fresh petitions in the Supreme Court have frozen all progress.

This is not just a courtroom issue. It is a drag on growth. Jaypee’s resolution ties up ₹16,000 crore. That is money that could be paying workers, buying cement and steel, and helping banks lend to new borrowers.

Economists estimate that every ₹4 invested adds ₹1 to GDP annually. So this one case alone is costing India ₹4,000 crore in lost GDP every year. If the freeze continues for five years, that becomes ₹20,000 crore of lost output. Enough to fund new metro lines, logistics corridors or thousands of small business loans.

And the job impact is just as large. Construction supports workers at every level, from labourers and drivers to engineers and suppliers. Jaypee’s blocked capital could have generated 1.5 lakh jobs for a full year. But both homebuyers and workers remain in limbo.

Now zoom out. Across India, nearly 12,000 corporate insolvency cases have been pending before NCLT. A significant share of them are either unresolved or delayed far beyond the legal limit.

If even 6,000 of these tie up just ₹100 crore each, that means ₹6 lakh crore of capital remains frozen. Applying the same GDP ratio, that is ₹1,50,000 crore of output lost each year. Equivalent to nearly 0.5% of India’s GDP and larger than many state government budgets.

This is a conservative estimate. The ₹6 lakh crore figure is based on IBBI and RBI data, along with Parliamentary reports and financial sector disclosures. Many pending cases are in real estate, infrastructure, power and manufacturing, where average claim values run much higher (in thousands of crores). But even at the lower bound, the economic cost is undeniable.

Worse still is the recent Supreme Court verdict on Bhushan Power and Steel. This company had already been successfully resolved through the IBC in 2019. JSW Steel acquired it, paid over ₹19,000 crore to creditors, and restarted operations. Jobs were saved. Output resumed. The resolution was hailed as a model example of how the IBC could work.

But in May 2024, five years later, the Supreme Court overturned that resolution following a long-pending appeal. The Court ordered liquidation instead.

As former IBBI chairperson M. S. Sahoo says, this verdict, though legally correct, delivers a “capital sentence” not only to the company but also to the credibility of the IBC. The judgment reflects a worrying trend where commercial transactions, once resolved, can be reopened after years, undermining the entire point of time-bound resolution.

This brings us to a deeper and uncomfortable question: who should we hold accountable for this mess: our policymakers or the judiciary?

The IBC was envisioned as a special legislation to free up India’s capital and resolve business failure swiftly. But today, the entire process is vulnerable to collapse not because the law is poorly drafted, but because Parliament never fully insulated it from judicial gridlock.

Let’s be clear. The IBC set up a bespoke, technical system: the NCLT for initiating and supervising insolvency proceedings, and the NCLAT as a specialised appellate forum. This was supposed to create a closed-loop system where time-bound resolutions could be delivered by those equipped to understand commercial realities.

But Parliament inserted a final layer of appeal to the Supreme Court on “substantial questions of law.” In theory, this sounds limited. In practice, it has opened the floodgates for routine delay. Every time the NCLAT concludes a hard-fought resolution, litigants run to the apex court. And the IBC’s greatest strength, finality within a fixed timeline, gets erased.

If this is the system, why even have the IBC? Why build a fast-track resolution framework if it leads, eventually, to the same Supreme Court corridors from which we were trying to escape?

The irony is sharp. India has legislated judicial exclusion before. (And while this may be a contrasting comparison, I present it to highlight a structural inconsistency.)

The Delimitation Act, for instance, cannot be challenged in court at all. Electoral boundaries, once drawn, are considered beyond judicial review. Why? Because some functions require finality, even if not perfect.

If we accept that logic in political matters, why can’t commercial decisions under IBC be similarly protected? Why must every insolvency outcome, no matter how thoroughly examined, remain vulnerable to being reopened after years?

This is not about disrespecting the judiciary. It is about respecting the intent of Parliament itself.

The IBC was designed to prevent precisely the kind of legal limbo we now see in Jaypee, Bhushan Power and thousands of other cases. But if Parliament allows every NCLAT order to be subject to further scrutiny, and the Supreme Court agrees to hear these appeals, then the Code becomes little more than a set of guidelines, not law with teeth.

The danger is clear. If decisions can be undone years later, the risk for every investor, lender and developer rises sharply. India already ranks among the slowest nations in resolving contract disputes.

While Singapore settles disputes in 150 days and South Korea in 240, India takes 1,445 days. That delay becomes a cost, raising borrowing rates and driving away long-term capital.

Yet the IBC still holds potential. When it works, it works well. But the core principle that once a plan is approved, it must be implemented without delay or reversal must be defended.

Certainty builds trust. Trust unlocks capital. Capital funds jobs. Jobs build growth. Clearing courtroom jams is not just a legal fix, it could be one of India’s biggest economic wins.

Deepesh Gulgulia is a Law student. He tweets at x.com/@deepeshgulgulia.