Politics

Explained: How 2021 NEET Admissions Became A Messy Affair, And How Some States Can Complicate It Even Further

- Here's a step-by-step explanation of how post-NEET-PG counselling became a tangled mess, and why it could get even worse from here.

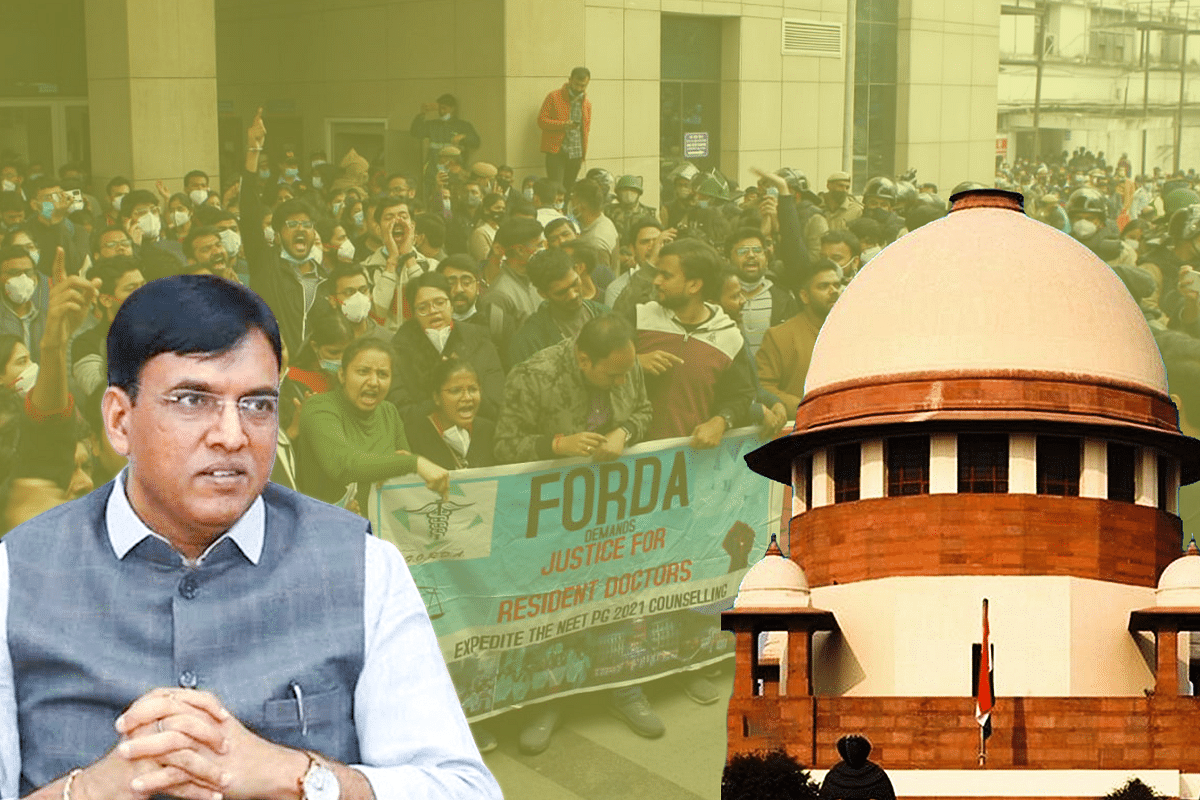

Representative image

As groups of protesting resident doctors at the government-run Safdarjung hospital came to a violent face off with the police authorities on 27 December, the issue of months-long delay in post-NEET exam counselling got highlighted by the mainstream media much more prominently.

The junior doctors have been protesting for weeks, demanding that the counselling to fill the seats, particularly in Post Graduate courses under All India Quota, is kicked off as soon as possible because the process is already late by more than six months.

The importance of quick resolution cannot be emphasised enough. There is complete shutdown by doctors in leading government hospitals in the national capital such as Safdarjung, Ram Manohar Lohia, Lady Harding, Lok Nayak, Ambedkar, GB Pant, GTB, DDU and Hindu Rao. The future of more than 40,000 doctors is at stake. With a third Covid-19 wave on the horizon and healthcare staff already in short supply, strike by doctors is the last thing India needs.

The National Eligibility cum Entrance Tests for admissions into medical colleges to undergraduate (NEET-UG) and postgraduate courses (NEET-PG) were held in September this year and result was also declared in the same month. In 2020, the PG exam was conducted in January and counselling got over by April. But this time, the exam was scheduled for April which got postponed due to the second Covid-19 wave.

The counselling for allotment of seats for NEET-PG successful candidates was to happen on 25 October but the Supreme Court ordered the Union government to halt the process and not resume it until the apex court decides on the legality of centre’s decision to give 27 per cent reservation for OBCs and 10 per cent reservation for Economically Weaker Section (EWS) in All India Quota (AIQ) Scheme for undergraduate and postgraduate medical/dental courses (MBBS/MD/MS/Diploma/BDS/MDS) from current 2021-22 academic year onwards.

First, understanding how the whole thing works is important.

There are three types of medical seats (in PG and UG courses):

-seats in state governments-owned/aided/run colleges;

-seats in central government institutions;

-and seats in All India Quota (AIQ) which is formed by seats surrendered by various state governments for them to be filled via centralised counselling.

For AIQ, states surrender 15 per cent of their seats in UG courses and 50 per cent seats in PG courses.

Now, it’s pertinent to note that only in this AIQ category, there was no OBC reservation until last year however, 85 per cent of the UG seats and 50 per cent of the PG seats at the state-level did follow OBC quota and filled the seats as per their own state OBC lists. These were reserved for domiciles of the states in which these colleges were located. Similarly, in central government institutions like AIIMS, OBC reservation was followed as per the Central OBC list. In addition, SC/ST quota was also there.

Also, even in AIQ, SC/ST reservation was followed but not the OBC one. This changed on 29 July when Modi government cleared the 27 per cent OBC as well as 10 per cent EWS quota for the AIQ list.

A short history of AIQ is also in order here. This came into existence in 1986 when the Supreme Court issued directives to provide for domicile-free, merit-based opportunities for students from one state to study in a medical college in a different state. There was no quota in AIQ. Ironically, in 2007, 15 per cent reservation for SCs and 7.5 per cent for STs was introduced by the Supreme Court itself.

In the same year, the Central Educational Institutions (Reservation in Admission) Act came into force which provided for 27 per cent reservation to OBCs but this was not implemented in AIQ and only the Central Educational Institutions like Safdarjung Hospital, Lady Harding Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, Banaras Hindu University etc followed it. In July, Modi government extended it to AIQ too along with the EWS quota.

In September, a batch of pleas challenging this decision were admitted by the Supreme Court which asked probing questions to the centre, particularly on the criteria of Rs 8 lakh annual income as 'creamy layer' upper limit for qualifying for EWS category quota. “You cannot just pick Rs 8 lakh out of the thin air and fix it as a criteria. There has to be some basis, some study. Tell us whether any demographic study or data was taken into account in fixing the limit. How do you arrive at this exact figure? Can the Supreme Court strike down the criteria, if no study was undertaken?,” the bench asked the government.

Nonetheless, the long and short of the story is, the court has ordered the centre to stop the counselling, the case is still sub-judice and the court is on holiday since 20 December and will hear this matter on 6 January.

There is a saying that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. But it seems that Modi government couldn’t resist from violating this dictum. Medical PG admissions have been going on fine for the last 13 years. Last year, the SC had denied entertaining pleas from Tamil Nadu which demanded that 50 per cent reservation should be given to OBCs for seats surrendered by Tamil Nadu government colleges for the AIQ national list.

However, it allowed the petitioners to approach the Madras High Court which, a month later, observed that there was no constitutional impediment to the extension of reservation for OBCs in AIQ and directed the central government to constitute a committee to facilitate the same after deciding on the percentage.

The centre could’ve contested this but it chose to get trapped, perhaps thinking that extending OBC reservation to the AIQ list would be a cakewalk with little legal resistance and a boost in its image as a champion for social justice. PM Narendra Modi hailed his government's decision as one which ‘will immensely help thousands of our youth every year get better opportunities and create a new paradigm of social justice in our country.’

Very likely, the government wouldn’t even have anticipated that the highest court in the country would jeopardise the whole admission process by highlighting potential arbitrariness in deciding the creamy layer upper limit in EWS quota.

To be sure, this issue of EWS is not so complex and it will be sorted. The real issue is not even being mentioned let alone being considered for addressing. It’s a masterclass in classic bait and switch.

The main problem is certainly not with the EWS quota. Imagine we are talking about MBBS doctors who are vying for PG seats. No matter which way you look at it, they are already in creamy layer, earning more than Rs 8 lakh for sure whether they are in OBC or EWS. So, the real travesty is reservation in PG admissions itself. It’s no better than the quota in promotion.

But is anyone talking about it? No.

We are discussing inanities instead, whether the cap should be Rs 8 lakh or 12 lakh or other such random figure. It’s like fighting over colour of cushion covers in living room when the very foundation of the house is literally shaking and warning us of the impending collapse.

Even if one were to ignore this perversion, the Dravidian challenge stares us in the face. Even since NEET came into being, parties in Tamil Nadu have been rallying non-stop against it. It’s they who approached the Supreme Court first and then the Madras High Court to plead that the 50 per cent reservation given to OBCs in Tamil Nadu is also applied to AIQ list, especially for seats surrendered by the state. But how can that be done when there is 27 per cent reservation at the central level and it’s the Central OBC list that will be used to fill those seats?

Tamil Nadu’s present DMK government even asked the centre to remove it from AIQ system itself and let it fill all the seats in state medical colleges from the students from Tamil Nadu as per the state’s quota policy. Of course, making an exception to it is a challenge in itself but even if it’s done on principle that states can opt out of this, this is a slippery slope.

Moreover, the Supreme Court’s idea of domicile-free admissions itself which gives students opportunity to study in good colleges outside of their state will be in jeopardy.

At the same time, while the idea of DMK government or ideologues aligned to them may sound irrational on the surface, it may not be on a completely unsound legal footing. It’s a good legal angle to explore that while the Central OBC list is used for central institutions, how can it be used to give admissions in colleges owned and run by state governments. States like Tamil Nadu can very well argue that it would be better if reservation policies (or state OBC lists) are rather used to give admissions in AIQ. This is basically another way to kill the AIQ.

Another alternative is to have the AIQ but let OBC candidates from each state be decided as per the state OBC lists. This would be a massive scam.

Three-quarters of Tamil Nadu’s population is classified as OBC while it’s less than 20 per cent in Punjab, Delhi, Himachal and Uttarakhand. The AIQ PG quota will be flooded with MBBS OBC doctors from Tamil Nadu who will be so many in numbers that they will alone be enough to fill seats in many other states. The farce of overall 27 per cent official quota can be maintained but those who go through will be overwhelmingly Tamils.

The least bad option was to not introduce the OBC and EWS quota at all and let things be as they were for the last 13 years. The second least bad option is to continue with the Central OBC list for AIQ and stand up to political and legal challenges from States. (But remember, this is also not strictly fair as some states, even in the Central list, have much higher share of their population classified as OBCs than other states).

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest