Politics

Explained: How The ‘Article 35-A Lawsuit’ Can Right A Historic Wrong In Jammu And Kashmir

- Kashmir must be freed from the clutches of Article 35-A to make room for a constructive solution, which maximises peace, progress and prosperity for all.

- It will let new leaders with a liberating vision to take the place of old Sheikhs, injecting fresh development within the state.

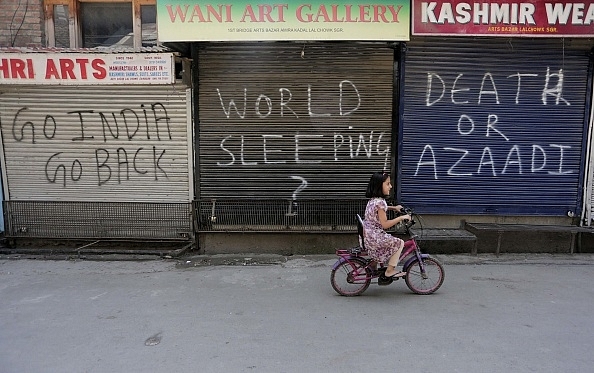

A Kashmiri girl rides bicycle in front of closed shops during restrictions in Srinagar. (Waseem Andrabi/Hindustan Times via GettyImages)

The dour British were notably unsentimental about Kashmir describing it as a sentry state. By contrast, India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, saw it as a siren state. Both acted in accordance with their viewpoints. One succeeded and the other failed.

Along comes a lawsuit which for the first time seeks to upend the Nehruvian compact and rights a historic wrong. Filed by the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Study Center in the Supreme Court of India, it has generated a storm. The suit has been widely quoted in the media for its key assertion that, ‘Article 35 A of the Constitution of India has been added vide Constitution (Application of Jammu & Kashmir) Order 1954 by the President of India, is beyond his power and jurisdiction and therefore it is unconstitutional.’ All the political parties and the separatists in the Valley have united in agitating against it and are making open threats bordering on insurrection. What gives here that has caused the Kashmiri oligarchy to make common cause?

Media and other commentators have not cared to study the lawsuit directly and evaluate its merits independently. The court of public opinion is not the court of law. This was demonstrated most recently in the Supreme Court throwing out the case filed by Roots in Kashmir dealing with their demand for justice for the genocide committed against the community. What raises questions is that the advocate for the petitioner, Rameshwar Prasad Goyal, turns up on Google search, to be or have a namesake that was heavily censured by the Supreme Court for lending his name for cases where he had never been briefed by the litigant nor did he show up. The other advocate Barun Kumar Sinha seems to have represented the petitioner, Sandeep Kulkarni, on other Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) cases. K N Bhat is the senior advocate and a Google search reveals that he served as Additional Solicitor General of India. Presumably, it is he who will go head on head against Attorney Fali Nariman who was hired by the J&K state government to defend against the lawsuit.

The Article 35-A lawsuit has several novel representations within it, reflecting shrewd thinking and some creativity that has been singularly lacking to date in the public interest litigations dealing with the state. However, the lawsuit needs more rigour, and it overreaches in places, which will provide unnecessary openings for the oligarchy which has run Kashmir to punch holes in it.

For example, the Instrument of Accession was signed on 26 October 1947, and not on 27 when Indian troops landed in Srinagar. Nonetheless, the timeline of the constitutional events in the preamble shows clearly that Article 35-A was implemented a full seven years after accession, so it’s possible termination in no way invalidates the accession. Hopefully, by the time that actual arguments are heard, the petitioners will have cleaned and refined their arguments further. Ditto for the defendants so that there can be an informed hearing of this case.

The first assertion of the lawsuit is:

For support, the documentation that is advanced is that Kashmir acceded to the federation that was set up by the British under this 1935 act. Here is the problem with the lawsuit’s starting point. The Federation never became official because it did not get the requisite quorum among the Princely States. Therefore, the court is not going to accept this argument. But while the petitioner is precisely wrong on their historical narrative they are approximately right and there is a better construct in history for a stronger, useful assertion, which is founded on the paramountcy of power (more on that later in this article).

The lawsuit then lays the second foundational pillar for its case by invoking Section 7 of the Indian Independence Act, 1947 which provides for the consequences of the setting up of the new dominions. It invokes the abolishment of the Privy Purses to the Princes judgement by expanding the interpretation of that ruling. Specifically, Section 363A (a) states ‘The Prince, Chief or other person who, at any time before the commencement of THE CONSTITUTION (Twenty-Sixth Amendment) Act, 1971, was recognised by the President as the Ruler of an Indian State or any person who, at any time before such commencement, was recognised by the President as the successor of such Ruler shall, on and from such commencement, cease to be recognised as such Ruler or the successor of such Ruler.’

If the special rights accorded to the sovereign ruler were extinguished because they were viewed as legacy baggage and it did not generate any hue and cry within the state then why are threats emanating if rights that only a special class of citizens, the new, self-anointed, rulers of Kashmir enjoy are questioned, going forward? With the counterparty signatory to the accession no longer a deemed recognised special party all obligations become moot. The lawsuit boldly asserts:

This is a novel argument but then, has not the state and its oligarchy and the separatists taken a variant of the very same position that with the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, Article 370 is now permanent?

The lawsuit then moves to the third and core assertion, namely that Article 368 in the Indian Constitution gives supreme authority only to the Parliament of India to add any provision to the Constitution. This does not limit the President from amending or modifying or varying an existing provision as the Supreme Court has observed in several prior judgements. For reasons that are not clear the lawsuit does not provide the smoking gun and that is to quote the specific provision in The Constitution Order 1954 application to Jammu and Kashmir, Section 4 Part III (j) “After article 35, the following new article shall be added, namely….”. This is followed by an enumeration of the rights of permanent citizens as determined by the Legislative Council of the state which has been used for repugnant actions bordering crimes against humanity. What the lawsuit omits is that if the intention was to empower the President to add such Articles then there is clear precedent in Article 240, applicable to Union Territories, where there is explicit authority for the President to overrule, repeal and modify Parliament and make regulations for peace, progress and good government. This did not happen.

Now that the weapon used to murder the Indian Constitution has been identified what remains is the motive. It is here that digging deep into history uncovers an interesting article. Dr Krishanlal Shridhasani, a noted journalist of India, wrote in Amrit Bazar Patrika on 29 July 1952: “Nehru wanted to keep Kashmir as free of the Indian Constitution as possible. Insiders know by now that … he has begun to feel that our Constitution is so binding as to impede rapid progress.’ So, already prior to this Order, Nehru had been flagged for his intent to possibly circumvent the Constitution. But it is Chief Justice Anand who lets us into the truth of what might have happened. In his book The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir, he states, ‘In accordance with the agreement between the representatives of India and Pakistan, that the State Legislature would have the power to make special provisions for the ‘permanent residents,’ it was deemed necessary that some provision be made in the constitution to cover that case. Accordingly, Article 35A was inserted by Section 2(4) (j) of the Order, 1954.’ So, there, notwithstanding the state subject history, there was an external instigator of this extra-constitutional addition never mind that Pakistan abolished this state subject privilege in 1974 for those living in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir!

The lawsuit’s final plea is that Article 35-A is violative of the constitutional provisions because it creates two classes of Indian citizens, is highly discriminatory, curtails fundamental rights and violates the directive that the state shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.

It is interesting at this stage to study the response by the state government represented by Fali Nariman where the temporary Article 370 is held to be paramount to Article 368 of the Indian Constitution. The first counter is to invoke a time bar, statute of limitations argument, “After this length of time when the provisions enacted in Article 35-A of the Constitution have been continuously acted upon and treated as valid, the same ought not to be permitted to be challenged.” The second argument is more revealing wherein the de facto argument is advanced which perhaps concedes a weakness on de jure grounds, “the instant petition seeks to upset settled law, accepted and complied with by all.” The state then goes on to assert that the apex court has already ruled in two cases in 1960s that the J&K government’s right to make exclusive provisions has been upheld.

In terms of paramount power and the relative positions of Article 370 vis-a-vis Article 368, the Supreme Court judgement of December 2016 is relevant when in the State Bank case the Supreme Court ruled, “It is thus clear that the state of Jammu & Kashmir had no vestige of sovereignty outside the Constitution of India and its own Constitution, which is subordinate to the Constitution of India. It is therefore wholly incorrect to describe it as being sovereign in the sense of its residents constituting a separate and district class in themselves. The residents of Jammu & Kashmir, we need to remind the High Court, are first and foremost citizens of India. Indeed, this is recognised by Section 6 of the Jammu & Kashmir Constitution. We have been constrained to observe this because in at least three places the High Court has gone out of its way to refer to a sovereignty which does not exist.”

In terms of time bar, notwithstanding the egregious judgement against the Kashmiri Pandits, the Courts in India have generally been reluctant to permit an ongoing, systemic injustice escape through such a provision. The very fact that the defendant’s filing reveals that there has been a litany of cases against the state’s discriminatory practices belies the de facto practice argument that it is accepted and complied by all.

Moving on from the law to life provides damning de facto evidentiary material to support the petitioner. Here is a relevant quote from the case of Bachan Lal Kalgotra v. State of Jammu and Kashmiron the discrimination because of 35-A, ‘In view of the peculiar Constitutional position obtaining in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, we do not see what possible relief we can give to the petitioner and those situate like him. All that we can say is that the position of the petitioner and those like him is anomalous and it is up to the legislature of the state of Jammu and Kashmir to take action to amend legislature, such as, the Jammu and Kashmir Representation of the People Act, the Land Alienation Act, the Village Panchayat Act, etc so as to make persons like the petitioner who have migrated from West Pakistan in 1947 and who have settled down in the State of Jammu and Kashmir since then, eligible to be included in the electoral roll, to acquire land, to be elected to the Panchayat, etc. This can be done by suitably amending the legislation without having to amend the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution.

In regard to providing employment opportunities under the state government, it can be done by the government by amending the Jammu and Kashmir Civil Services, Classification of Control and Appeal Rules. In regard to admission to higher technical educational institutions also, the government may make these persons eligible by issuing appropriate executive directions without even having to introduce any legislation. The petitioners have a justifiable grievance. We are told that they constitute nearly seven to eight per cent of the population of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In the peculiar context of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, the Union of India also owes an obligation to make some provision for the advancement of the cultural, economic and educational rights of those persons. We do hope that the claims of persons like the petitioner and others to exercise greater rights of citizenship will receive due consideration from the Union of India and the State of Jammu and Kashmir. We are, however, unable to give any relief to the petitioners.’

If the anomalous is deemed illegal then the liability of the state for past sins will be very high indeed!

We address now the 1935 understanding and provide the de facto operating reality of the Instrument of Accession which was designed to mimic the status of Princely Kashmir under British suzerainty. Indian commentators ascribe greater sanctity to the commitments to the Maharaja which the Maharaja fully knowing his royal history did not himself expect based on the past practices of the dour British. To appreciate this one should start with the Treaty of Amritsar. Article X of the Treaty stipulated that "Maharajah Gulab Singh acknowledges the supremacy of the British Government and will in token of such supremacy present annually to the British Government one horse, twelve shawl goats of approved breed (six male and six female) and three pairs of Cashmere shawls". This clause placed boundaries on Clause I, ‘the British Government transfers and makes over forever in independent possession to Maharajah Gulab Singh and the heirs male of his body ….’.

How these two clauses were supposed to operate coterminous was spelled out simply and elegantly by Henry Lawrence, the British Resident at Lahore, while writing to Gulab Singh in 1847 when he made the "independent possession" conditional to his capacity to govern his subjects with justice and equanimity. So subordinacy had implicit conditional autonomy and there could be intervention if circumstances dictated so. The numerous examples of British intervention in Kashmir include the direct takeover of Gilgit.

An agreement was signed on 26 March 1935 between the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir and the representatives of the British Indian government by which the Gilgit Wazarat, north of the Indus and its dependencies were leased out to the British for a period of 60 years. There was the forced abdication of the throne by Pratap Singh and the appointment of a British resident who controlled the Budget, the leading of land, educational and commerce reforms and many other actions including the appointment of Lieutenant Colonel E J D Colvin as Prime Minister of Kashmir in 1933! The wily Sheikh Abdullah and his descendants took maximum advantage of Indian vulnerability at the United Nations and negotiated to convert the Instrument of Accession into a (temporary) China Wall where none existed before.

So, it was not the case of Kashmir, the beautiful woman, but India which ended up as the damsel in distress. Naive Indian officials and commentators lacking the history of practice and precedence let the Sheikh consolidate his position. Nobody cared to emphasise that at the time of Independence there were 565 states linked to India. Here is what on 5 July 1947, the government of India released as the official policy stating:

Is any other state harping back to that commitment to them in the very same Instrument of Accession that they signed?

The final de facto understanding for the court which the petitioner should and did not advance is the economic impact of the 35-A law and regulation in Kashmir. This is a rapidly burgeoning legal field in the West but is still in its infancy in India. To understand the reason why the oligarchs in Kashmir are opposing revocation of Article 35-A is because it is pro-poor and anti-rich. Article 35-A has given monopoly power to the oligarchy in Kashmir permitting them to concentrate wealth immeasurably. Free market theory would predict that elimination of Article 35-A will cause land prices to go up instantly benefiting the average resident of Jammu and Kashmir whose primary asset value is tied to his land. It will lead to capital investment and job employment, which will benefit the poor the most. If the buyer pool is restricted to the oligarchs of Kashmir then they set the price and there is a net transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich. The statistics support this thesis.

First, quantitative data is coming out on the staggering real estate wealth that the separatists’ leaders have amassed. The other measure is the Gini coefficient which measures inequality and for Kashmir has been rising the fastest. (The other state is Himachal Pradesh which has similar land restrictions that the votaries of Article 35-A point to and suffers similarly.) If one looks at the public records, then one sees that orchard land ownership is highly concentrated in the Valley with 17 per cent of the population owning more than 50 per cent. When one factors in the likely benami ownership then the actual numbers are probably much, much higher. Economic returns on orchards are much greater than their counterpart elsewhere suggesting Kashmiri land specifically and J&K land generally is undervalued because of suffocation of demand.

A study published by the State Industries and Commerce Ministry a few years back confirms the absence of demand factors and showed that while Jammu got Rs 938.65 crore in outside investment (not a great amount) Kashmir Valley got only Rs 3 crore! These numbers are cumulative numbers since inception. If Article 35-A is removed, Jammu and Ladakh would have an investment boom and Kashmir Valley would follow suit once conditions stabilised. But that is how financial capital markets behave and flows occur. They reward good behaviour and penalise bad, a logical behavioural economic model which the Article 35-A law has distorted severely. So, a highly predatory economic strategy directed against the J&K public and especially the Kashmiris masses by the Kashmiri oligarchy has been masked by sweet talk of special status, Kashmiriyat and unique culture. There is now draconian punishment for private corporate enterprises, which practise monopolistic behaviour but public institutions and especially states need to be held to even higher standards and not lower.

What the apex court must determine is whether there has been Justice and equanimity or not and whether it is time to intervene judicially, correct a historic wrong and drain the swamp. An earlier ruling in the case of Rehman Shagoo Vs State of Jammu and Kashmir stated:

Different context but the principle remains. To follow the poet Amir Khusro, if there is repugnance, Kashmir is it Kashmir is it. If the Supreme Court does remove Article 35-A then it can free up all the political parties and eventually Parliament to work on a constructive solution to Kashmir which maximises peace, progress and prosperity for all, not the least of who include the Kashmiri Pandits, the West Pakistan refugees, the Nepalese and other rootless State subjects.

It will permit retirement of the old Sheikhs and the emergence of new leaders who bring a liberating vision. They will embrace and leverage Private Public Partnerships but more importantly free market partnerships between private citizens that will inject development within the State. Jammu will lead the industrial revolution, Ladakh renewable energy and tourism and Kashmir, agricultural productivity and hydroelectric power. The future can be bright indeed.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest