Politics

Fadnavis Fiasco Shows BJP Is Up Against Newton’s Third Law: Its Rise Creates A Stronger Opposition

- The party should read Newton’s third law of motion: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

- A strong centralising party will, almost as if in reaction, create the conditions for a strong coalition of rival parties as a counter-weight.

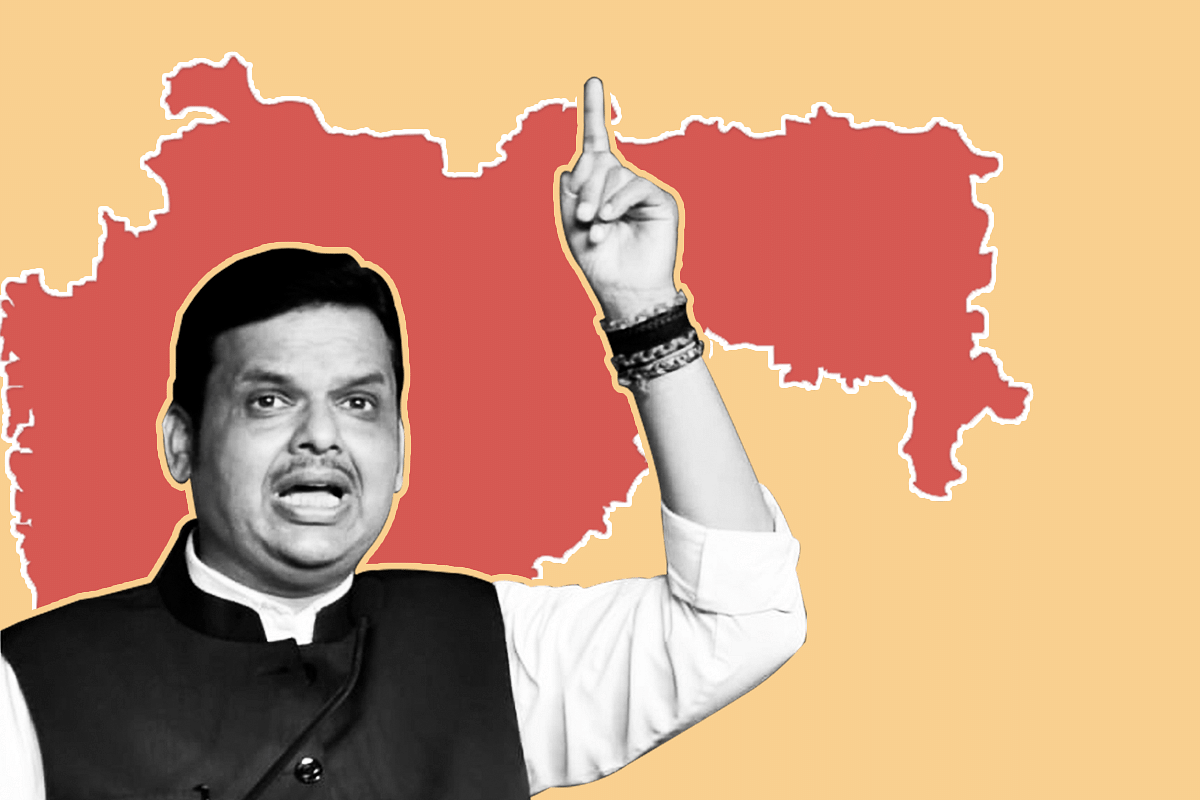

Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis.

If Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has egg on its face after the Fadnavis Fiasco in Maharashtra, where the Chief Minister had to resign within days after taking the oath and failing to get the support of the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), it has only itself to blame. It is now certain that a Shiv Sena-Nationalist Congress Party-Congress coalition will take office.

The party has to learn that it does not have to retain power at all costs. It must also acknowledge that its regional power trajectory may not be the same as it was in its first term of 2014-19. If the slogan Congress-mukt Bharat drove BJP ambitions in the first term, this time around the electorate – and many smaller parties – have good reason to band together to keep the BJP out. It is worth noting the BJP’s shrinking footprint: Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Karnataka are the only three major states the party rules on its own currently.

The party should read Newton’s third law of motion: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. A strong centralising party will, almost as if in reaction, create the conditions for a strong coalition of rival parties as a counter-weight. This is what is happening right now in the states, as regional and weak national parties tie up to keep the BJP out of power.

Trying to resist this trend is foolish, unless it happens in the natural way, which is through the emergence of strong regional leaders in the BJP who can pull in the vote on their own.

It is not the BJP’s god-given right to rule all of India. It is also not a healthy thing for a democracy to not have worthwhile alternatives. It is this dynamic that the BJP is up against, and neither the personal popularity of Narendra Modi nor the organisational abilities of Amit Shah can go against the tide.

The electorate gave Modi a huge mandate just six months ago, and, to its credit, it is also focusing on delivering big-ticket change and some ingredients of reform that will boost growth. Trying to win every state election is not necessary to fulfil this mandate.

In Maharashtra, as in Karnataka last year, the BJP simply did not have the mandate to rule without a partner, and since independents were not easily available to fill the gap, the Shiv Sena called the shots. The BJP had two options: one was to give in to the Sena’s demand for the chief ministership, and the other was to stand on principle and stay in the opposition.

This was what Fadnavis chose to do two weeks ago. But what changed in just over a week? Clearly, when negotiations between the Sena, the Congress and the NCP seemed headed for some success, Fadnavis threw his hat in the ring without a clear mandate from the NCP leadership. Claiming a majority when only one man – Ajit Pawar – was willing to sign on was unwise, given the opposition of Sharad Pawar.

This rush to power without the numbers is inexcusable. In the process, the BJP – both the central and state leadership – have not only lost face, but also a lot of the moral high ground and the sympathy factor that Fadnavis was entitled to when he chose to step aside when he did not have the numbers.

By trying every trick in the book to retain power, Fadnavis has (1) given the Sena a new lease of life and additional will to hang on to power; (2) built the credibility of Sharad Pawar, who now holds all the aces; and (3) allowed the Congress to get a share of power in India’s richest state.

Thanks to the scare the BJP gave to this unnatural alliance, the trio have good reason to bury their differences for a longer period of time than earlier expected. The alliance will anyway come under strain at some point, given its contradictions, but in the next one year, pride alone will keep it going. The Sena has a point to prove to the BJP, and Uddhav Thackeray will be willing to make sacrifices to prove it.

Modi’s second tenure may be different from his first in two ways:

One, the party will find the opposition harder to divide unlike the first term. This is because their survival depends on staying together.

Two, the BJP could, however, make bigger gains in areas where it is not traditionally strong. With its resources and the popularity of its national leadership, states which never warmed up to the BJP will be more than willing to give it a better haul of seats, if not a mandate to rule. What doesn’t work for the BJP in the states where it is already strong will work for it in states where the voter may be tiring of the regional parties now in power (eg, West Bengal).

It would be good if Modi and Shah were to focus less on winning each state and instead built bridges with the national opposition to buy their support for major economic, political and judicial reforms that are long overdue.

The harvest of votes can come later in the states, if the Centre is seen to be delivering on the May 2019 mandate.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest