Politics

Kejriwal Looks Set For Another Big Win in Delhi; What BJP Can Learn From It

- Right now Kejriwal has no real challengers in either the BJP or Congress.

- Here are the key lessons national parties can learn from Aam Aadmi Party.

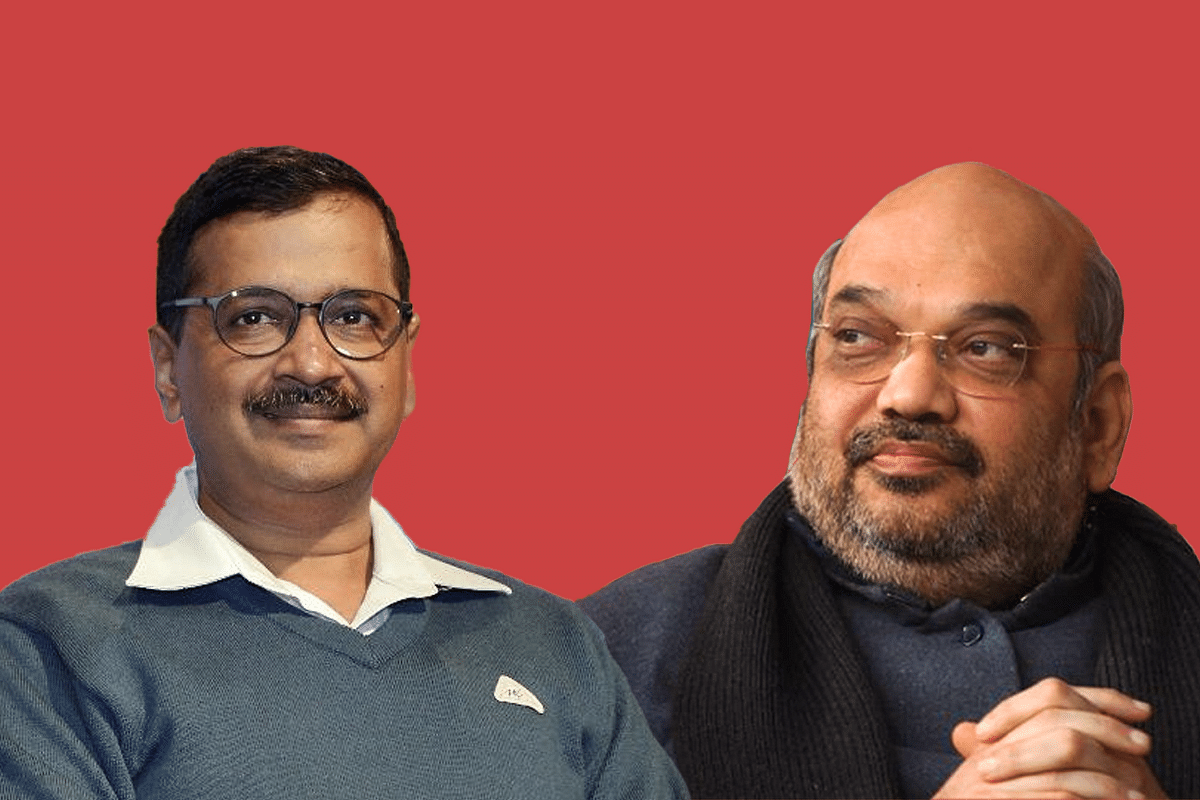

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal (left) and Home Minister of India Amit Shah.

An early-bird opinion poll on the Delhi assembly elections (due on 8 February) by C-Voter-ABP News gives a resounding sweep for Arvind Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), with a seat tally in the range of 54-64.

The poll leaves the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) far behind with 3-13 seats. At the lower end of the range, this would be almost as bad as the BJP’s performance in 2015 when it got three seats and the AAP 67 in a 70-member assembly. The Congress, which got zero, is estimated to get 0-6 seats. Even one seat is a gain for it.

While one should not credit this poll with too much insight, for the campaigning has barely begun, the results would not really come as a surprise to anyone since common wisdom predicts a clear Kejriwal win.

If the final results are anywhere near where the polls suggest, there are lessons in it for the BJP — lessons which it could learn from how AAP handled its victories and reverses.

The first lesson is clearly local leadership. It had five years to groom and create a rooted Delhi leader, but it did nothing and preferred to bask in the brand salience of Narendra Modi and the booth-level organisational abilities of party President Amit Shah.

This is a problem with all national parties, for they are seldom able to manage the tensions between developing strong regional leaders while also having a strong leadership at the national level. They tend to be either satrapies with weak central leadership (the BJP before 2013), or vice- versa.

This happens for two reasons: one, the national leaders tend to prefer weaker state leaders since stronger ones can challenge them tomorrow at the apex level. A strong regional leader like Modi could take on the BJP’s national leadership in 2013 precisely because the latter were not strong enough to hold their own. In close elections, leaders with charisma and popular appeal make all the difference between a creditable performance and a clear win.

The other problem is that regions tend to leave leadership decisions to the party bosses (case with both BJP and Congress), since they are unable to resolve their own local-level conflicts themselves. The Delhi bosses, on the other hand, do not have the good sense to allow state-level members to decide leadership issues through a vote, either by elected MLAs or even party panels.

For a party like the BJP, it is foolish to not let regional leaders develop, especially when there can be no anxiety about Modi’s own popularity levels inside his party and with the electorate at large.

If the BJP loses Delhi badly, it will be because it has not resolved this issue of Delhi’s leadership. If it does not do too badly, it will be because Delhi is a special case, where national issues often matter. One does not know what kind of impact the recent anti-Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests and counter-protests would have on the Delhi electorate. The chances are they may not have moved the needle much in the BJP’s favour.

Developing a state-level leadership also allows the latter to focus more on the failings of the party in power, something that cannot be done if the BJP depends too much on the top duo.

In contrast, look at how Kejriwal has made his strategy flexible enough to retain his brand equity with Delhi’s voters.

Kejriwal may not be popular with BJP or Congress voters, but he has shown the kind of agility and ability to respond to voter feedback that is missing in national parties at the regional level.

For example, when the BJP won all Delhi Lok Sabha seats in 2014, Kejriwal immediately realised that voters were not happy with his decision to resign so early in his first term, where he became chief minister with Congress support. In the February 2015 assembly elections thus he promised to remain focused as CM, shunning national ambitions with the slogan “Paanch Saal Kejriwal”.

Post-2014, after winning 67 of 70 Delhi assembly seats, Kejriwal again seemed to eye the national stage and constantly targeted Modi, but after he tasted defeat in the Delhi Municipal Corporation elections in 2017 and in Punjab, he realised that his future depended on how well he ran Delhi, and not by going after a popular national leader like Modi. He concentrated on education and health, two areas where he could make a difference, and, from the looks of it, many reports suggest that the public is reasonably happy with how public schools are being run and with the medical facilities to the doorstep by mohalla clinics.

Of course, it is easier for a state leader to learn lessons quicker than a national leader who has many irons in the fire, and hence cannot tailor his policy focus each time a state election comes along. But this tension can only be resolved by developing regional leaders who can hold their own in the local sweepstakes.

The BJP, assuming it loses Delhi when results are declared on 11 February, should focus on this one thing in all the states it is ruling. It is not without reason that it has been able to make a comeback with B S Yediyurappa in Karnataka, and managed to do reasonably well in Haryana and Maharashtra. A strong state leadership is not a guarantee of victory, but it is at least a first line of offence and defence for a national party against local challenges.

Right now Kejriwal has no real challengers in either the BJP or Congress.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest