Politics

Swachh Bharat: Man Behind India’s Biggest Clean-Up Drive Is Determined To Get The Job Done

- Far from the spotlight, Parameswaran Iyer is working tirelessly towards the goal of building a clean India.

- He may be at the helm of one of contemporary India’s most successful projects, but you wouldn’t sense that by speaking to him. Such is his humility.

- This is Iyer’s story, of a transition from government service to World Bank and back, this time in a pivotal role.

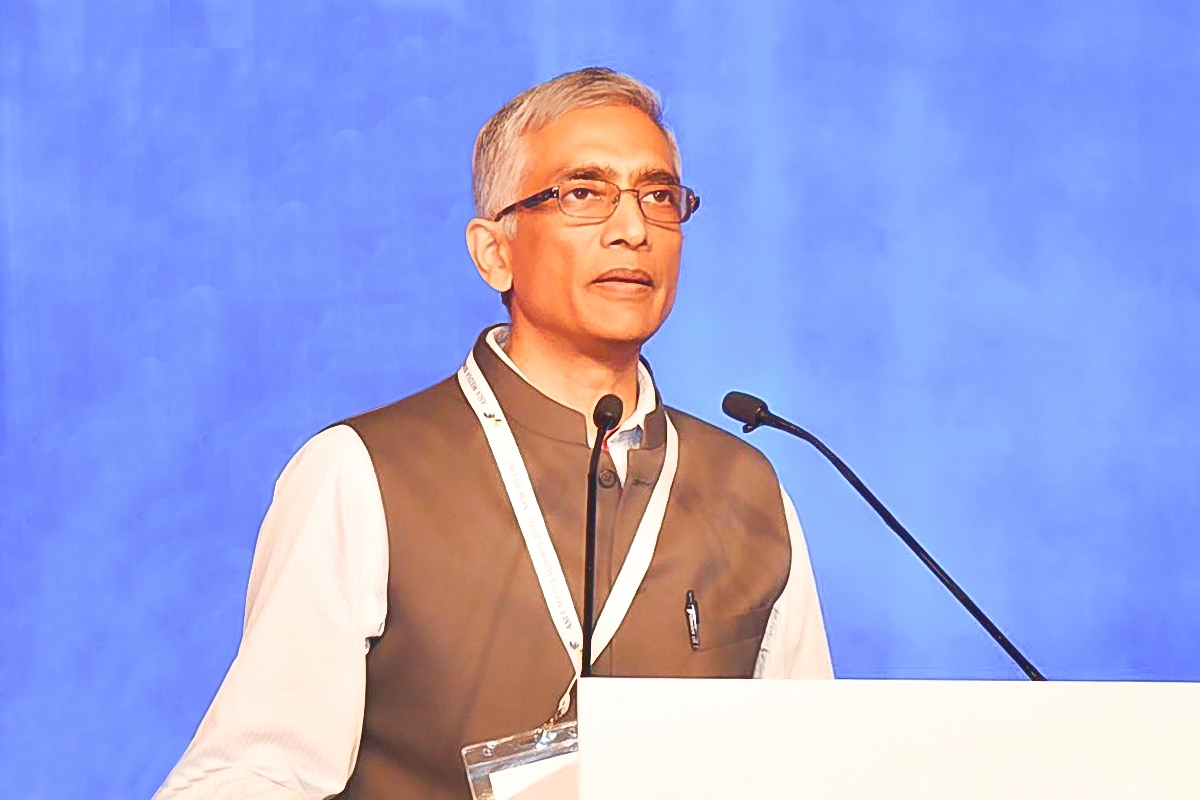

Parameswaran Iyer

In April this year, when he was addressing a large gathering in Bihar's Motihari to mark the anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s Champaran Satyagraha, Prime Minister Narendra Modi requested news channels to pan their camera to one man seated in the crowd.

“Government officials often remain anonymous and unsung. But there are stories that one desires to tell,” said Modi, introducing the crowd to Parameswaran Iyer, the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer heading the Swachh Bharat Mission.

Modi went on to share how Iyer was living comfortably abroad but returned at the request of the government to head a highly ambitious and challenging mission to clean India.

Iyer stood up and thanked the Prime Minister.

When we met Iyer at his New Delhi office – located in the only green-painted building in the central government offices (CGO) complex – he smiled at the mention of the incident and said, “He [Modi] was being incredibly generous. Of course, his message was for the entire team.”

Iyer may be at the helm of one of contemporary India's most successful projects, but he shies away from the spotlight. “Let's keep this interview about the project, please. Let's not make it about me,” he told us.

We couldn’t help but ask him about another incident that had him, briefly, in the limelight. Last February, Iyer had left a crowd jaw-dropped when he stepped inside a twin-pit toilet in a Telangana village and removed decomposed faecal matter with his hands.

Iyer’s eyes sparkle as he speaks about it now. “We wanted to end the stigma around it [cleaning the pit]. We wanted to show that a year after it has been covered, it's perfectly safe to empty a twin-pit toilet because the faecal matter has turned into manure,” he said.

What he is most kicked about is that after him, several officials have taken the lead in cleaning the pits, to set a precedent.

It was a novel experience even for Iyer, who has worked in various countries for 13 years as a sanitation expert with the World Bank. His memory of entering the pit that was once full of human excreta is so matter-of-fact that it's amusing.

“Think of it as a tall greyish-green sponge cake, about one metre in width.”

He opens his drawer, produces two small glass jars, and places them alongside a miniature model of a two-pit pour flush compost toilet. The jars are filled with manure from twin-pit toilets.

“One is from Pune, the other is from a village in Maharashtra,” he tells us.

Iyer believes that cleaning up a nation is everybody’s business. His formula is simple; he pitches for a “PM-CM-DM-VM model”, where the prime minister sets the goals, the chief minister supports it at the state level, the district magistrate leads at the local level, and “village motivators” work at the grassroots level.

The support at all levels, he says, has been huge. “That speech at the Red Fort was a game-changer,” he says, referring to Prime Minister Modi’s first Independence Day speech of 15 August 2014. Iyer says he was stunned at the mention of sanitation as a priority by a prime minister and immediately wanted to be a part of it. “I even felt homesick,” he says.

At that time, Iyer was working for World Bank in Hanoi, Vietnam. A year later, he was back in India as secretary at the Union Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation as well as cross-ministerial coordinator of the Swachh Bharat Mission.

Iyer, a 1981 batch Uttar Pradesh cadre, had quit the IAS in 2009, but, in a rare case, got the role that is usually reserved for a serving IAS officer. Before taking voluntary retirement from IAS, Iyer had worked for several years in defence and textile ministries and was also Bijnor district magistrate.

The Swachh Bharat project aims to rid India of the practice of open defecation by building necessary infrastructure such as toilets and piped water supply. “But a linked issue is behavioural change,” says Iyer, and adds that he believes that Indians are essentially a clean, sanitised people who have been following some unhygienic practices for a long time.

Iyer cites the National Annual Rural Sanitation Survey, which says 93 per cent of the people who have access to a toilet use them, to assert his point and says that one of the biggest achievements of the project is its right messaging. “Mass campaigns such as this need a trigger. In Vietnam, we told people that poor sanitation leads to stunting and that really worked. In India, we told people that defecating in the open is in turn making them consume excreta because it's mixing with drinking water. Do you want to eat excreta, we asked them, and it worked,” he tells us.

Personally, he is happy with the action undertaken at the basic level – the creation of Swachhagrahis, who act as grassroots motivators of behavioural change. “A lot of them are women. This Mission has given women a chance at leadership and empowerment like none other. It’s exhilarating,” he says.

Iyer's task – to clean India, no less – has a deadline of 2 October 2019, the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. In his large office, there is a white board that carries a scribble of the number of days passed, and the days left. There are five other figures, that sum up the progress and spell out the daunting task ahead: villages declared ODF (open-defecation-free), districts declared ODF, number of Swachhagrahis, percentage of rural India with access to toilets, and the number of villages rated on Swachhata Index.

So far, close to eight crore toilets have been built across India and over four lakh villages have been declared ODF.

When asked if this project required such a tight deadline, Iyer says, “If [there was] no deadline, there would be no momentum. The deadline is achievable.”

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest