Politics

Subaltern Rumblings In The Deccan: Broader Inferences Of Pinarayi Vijayan’s Rally In Karnataka

- Pinarayi Vijayan’s rally at Bagepalli offers multiple curious interpretations on the matter of Marxist electoral intent, and early insights on how our politics may evolve.

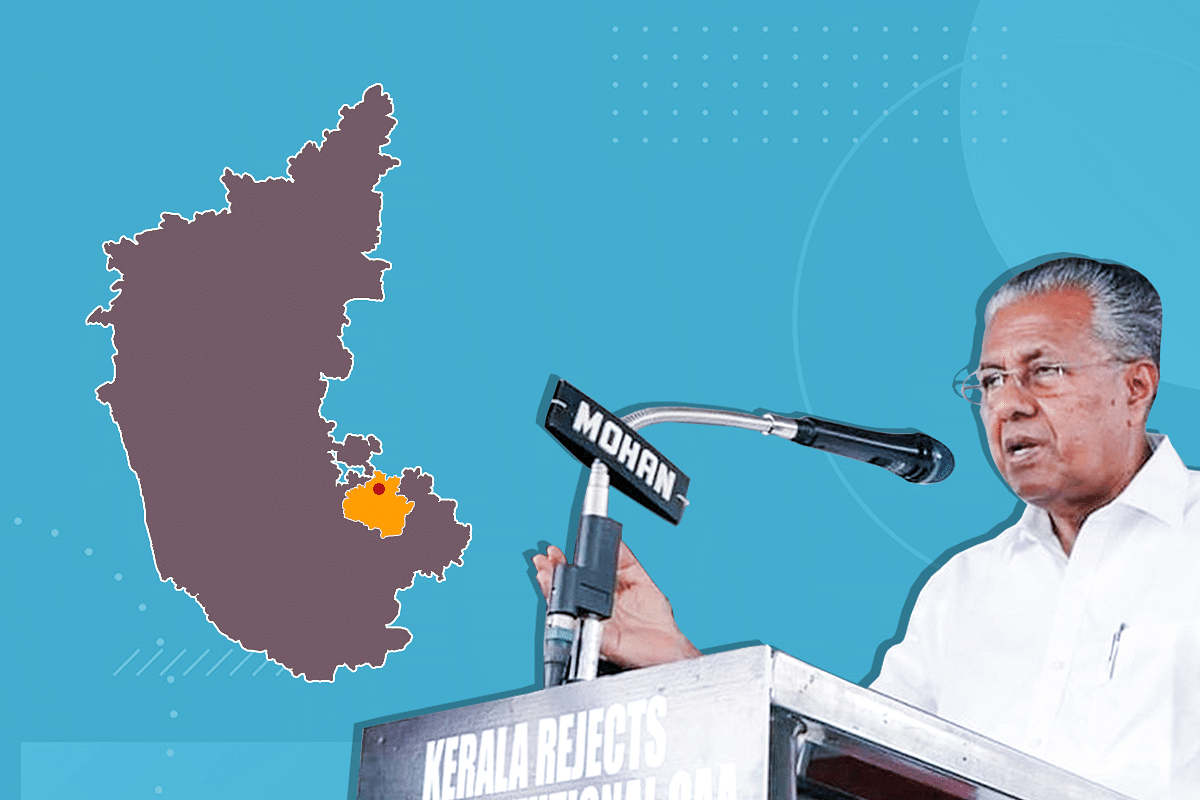

Kerala CM Pinarayi Vijayan's rally in Bagepalli.

Question: When was the last time a Communist Chief Minister held a rally in another state?

Answer: Can’t remember.

Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the CPM, conducted a political rally on 18 September in Bagepalli, Karnataka.

This is a small town near the Andhra Pradesh border, about 100 kilometres north of Bengaluru, and is the only assembly constituency in Karnataka where the Communists don’t lose their deposit.

In attendance on the dais at Bagepalli was another Malayalee politician – MA Baby of the Communist Party of India (CPI).

Bagepalli seat’s electoral history is given below. Note how the CPM polled 7 per cent even during an intensely bipolar national contest in 2019, and that they came a clear second in the last two assembly elections.

Using a Kannada translator, Pinarayi Vijayan spoke to a medium-sized crowd for a good hour on the importance and relevance of Marxism in today’s politics.

What he said there is as interesting as where he said it, because it offers indicators of how they may position themselves in the run-up to both the state elections in Karnataka next year, and the general elections of 2024.

Echoing Ram Manohar Lohia, Vijayan said that the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was a separatist force. Appealing to the minority segment, he said that the Hijab ban was a move by the RSS and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to make Muslims second-class citizens. Third, he hit the caste button and lamented at the victimisation of Dalits.

Then he got to the nub. The Congress, he said, had no strength left to face the BJP, since it was nothing more than a recruiting centre for the BJP today. And, in fact, the BJP and the Congress were actually the same because both promoted the corporate world.

Only the Communists, he meant, were inured from these perils and sins. And for effect, he asked the crowd to look at how effectively Kerala, under the Communists, had kept big business out of the state.

In essence, Vijayan offered a “Kerala Model” as a counter to a “Gujarat Model” (his way of countering ‘evil’ capitalism with welfare socialism), and, that the Communists were the only outfit capable of taking on the BJP at the national level.

Now, his reasoning may be baseless, since Kerala has bankrupted itself in its quest to become an ideal-albeit-unaffordable welfare state, and the only reason it hasn’t yet descended into economic chaos is because it is a perfect remittance economy.

Also, forget a national presence, the Left doesn’t even have a regional presence any more, save in Kerala and a few scattered pockets.

Nonetheless, Vijayan’s rally at Bagepalli offers multiple curious interpretations on the matter of Marxist electoral intent, and early insights on how our politics may evolve.

At one level, it can be read as identity politics versus identity politics. The Communists perhaps sense that, with a bit of luck, they can take over the caste-faith vote base from a crumbling Congress, and position themselves as the new protectors of the nation’s minorities and ‘oppressed classes’.

Another possible interpretation is that this is the Communists taking the fight into the enemy camp.

If Rahul Gandhi and the Congress can try to woo back the Christians of Kerala (whose largest political party left the Congress-led coalition for the Left in 2020) through a lengthy yatra and proxy protests at Vizhinjam port, then the Communists can jolly well try to cut the Muslim vote from the Congress in Karnataka – exactly at a time when Muslim disillusionment with the Congress is peaking there.

And what better way to press that point home, than by holding a rally at the one spot where the Communists continue to attract a sizeable chunk of votes?

A third interpretation is that this is an early attempt by the Communists, in the run-up to 2024, to cobble together a kernel around which a third front might grow.

While this may seem far-fetched presently, it is also the truth that a number of opposition parties would align more enthusiastically under a non-Congress banner.

The negotiations on seat sharing would progress more fruitfully, and these smaller parties would be able to retain their identities without being swamped by the Congress (which is exactly what happened to the Communists in West Bengal after they allied with the Congress at the centre in 2004).

This is not so outlandish if we accept that there are, in fact, only three identities which stand out in Indian politics – saffron, secularism, and socialism.

What readers must appreciate is that all political parties have to position themselves within an Indian electoral landscape cut into three unequal parts, with each part having distinct economic and cultural components.

One – a slightly-right-of-centre nationalist band,

two – a slightly-left-of-centre secularist band and,

three – a clearly-left-of-centre socialist-welfarist band (usually clubbed as a ‘third front’).

The BJP dominates the first and largest part; hence its stoic focus on promoting private enterprise and ensuring national security. The Congress and its derivatives command the second part; ergo, MNREGA and minority appeasement.

The third part, which is actually the second largest, is a patchwork quilt of regional forces who firmly place the welfare cart before the growth horse, and stand out in the crowd by crafting distinctive images for their outfits using local identities and quasi-Marxian rhetoric.

It includes the Maoists, the Communists, the Lohia-ite parties of the Gangetic Plains, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), both Andhra-ite parties, and the Tamil-Dravidian-Periyarists of the Deep South.

This classification gets blurred because of our first-past-the-post electoral system, and because cross-state unity between parties rarely translates into vote transfers.

For example, if the Shiv Sena and the Samajwadi Party allied in Andhra Pradesh, it would mean nothing, since neither party has any votes in that state.

However, since the three parts do overlap one another in places at a socio-economic level, the trick in every election is to get voters to move from one part to another.

This becomes all the more important to regional parties in the run-up to 2024, since it is patently evident that the Congress is disintegrating – in state after state, and in election after election.

Where will that departing vote go?

In such circumstances, it is wise to try and leverage what little support a party has, to capture a slice of this splintering pie, ally judiciously, retain its relevance, prevent the movement of votes to the BJP, and thereby boost its electoral prospects.

Look at how the Maoists won a dozen seats in the 2020 Bihar assembly elections; that is a far better return on investment for a regional political party, than the cumbersome tribulations of having to accommodate a withering prima donna like the Congress.

In fact, the 2022 Punjab elections showed that an opposition party like the AAP, with no past affiliations to the BJP, can attract substantial votes from the Congress. In a sense, that is exactly what the YSRCP in Andhra Pradesh, and the TRS in Telangana, did.

And lastly, parties like the Communists know that if they remain restricted to their provinces, without a national image, it is only a matter of time before they succumb to a relentless, still-expanding, BJP juggernaut.

In Karnataka, for example, what is the logical end-point of a party like the Janata Dal (Secular) (JDU) but oblivion, if it does not, at some point, revert to its original socialist roots?

What future does the JD(S) have beyond the Gowda dynasty, when its Kannada identity was long ago lost in a saffron deluge, and its socialism was appropriated by the Congress?

That is why, in the end, these parties will have to agglomerate on an unambiguously-Leftist platform, at the national level, if they want an easily-identifiable, distinct image in the current political landscape – and one which can attract both the minority and the welfare vote from the Congress.

It’s simply a matter of political survival, and options are dwindling with each passing day.

Perhaps it is this churn which may throw up a pan-Indian socialist party in the next few election cycles, to firmly replace the Congress, and become a counterpoise to the BJP.

The chances of such a party, or even a workable coalition, being formed before the 2024 elections seem bleak on date, but Pinarayi Vijayan’s rally at rural Bagepalli does hint at a possible next step in our political evolution. Watch this space.

Also Read: Truth Vis-A-Vis Post Truth Of Bharat Jodo

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest