Politics

Three Deputy CMs Are A Sign Of Weakness, Not Strength, Of Yediyurappa’s Government

- In Karnataka, the creation of three deputies to the CM is a sign of political weakness, not strength.

- Title inflation does not provide any guarantee to political stability or better governance.

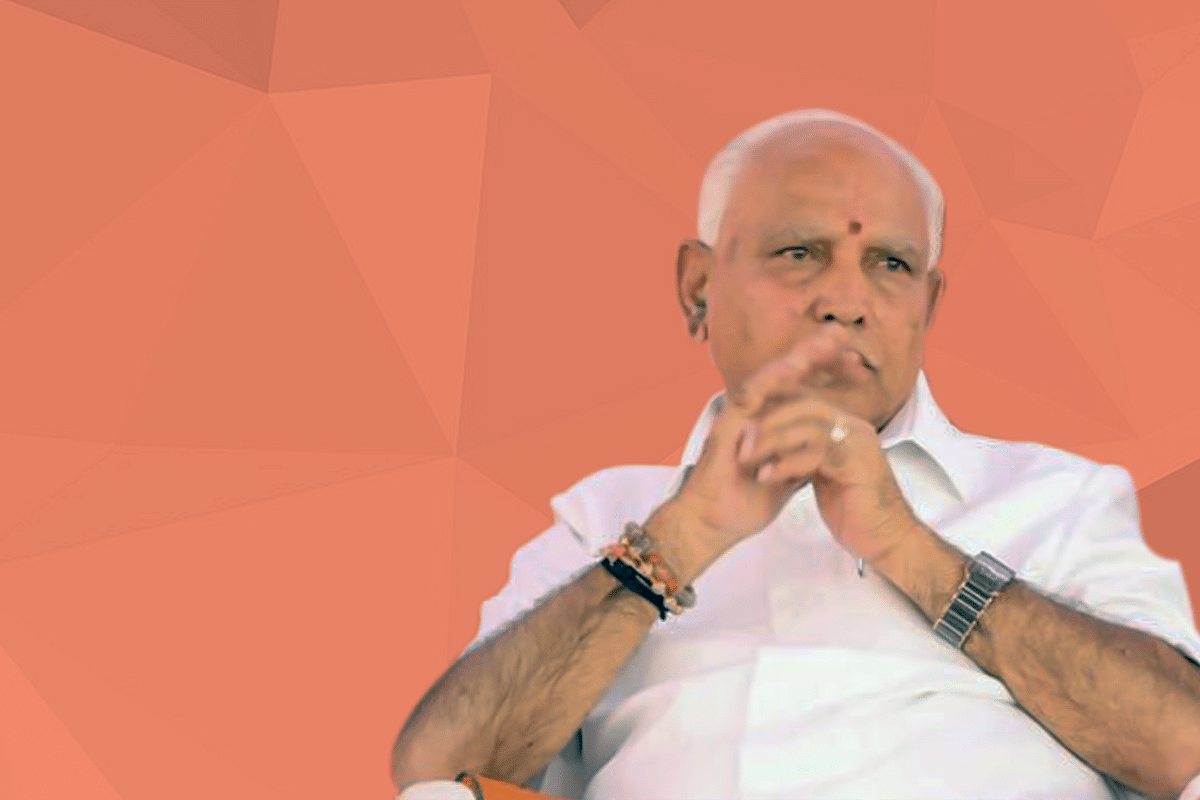

Karnataka Chief Minister B S Yediyurappa.

Title inflation is something you do when you have nothing more to offer an employee. In the world of business, it substitutes for a lower salary hike. What it does not do is equate title with job responsibilities.

In politics, title inflation compensates for the absence of real power. What it does not do is enhance governance or political stability. By agreeing to the high command’s suggestion that he manage potential dissidence by appointing three deputy chief ministers, Karnataka Chief Minister B S Yediyurappa has bought peace in the short term, even while leaving the scope for greater dissidence later. There is no guarantee that the current power structure will hold for the remaining four years of the assembly’s tenure.

On Monday (26 August), Yediyurappa appointed three deputies, one each from the SC, Vokkaliga and Lingayat communities – Govind Karjol, C N Ashwath Narayan, and Laxman Savadi respectively. In doing so, the Chief Minister has effectively left more senior colleagues, including one former chief minister (Jagadish Shettar), and two former deputy CMs, K S Eshwarappa, and R Ashoka, out in the cold. Not that the new deputies will have real power as implied in their grand titles; but the ego deflation that comes with being “mere” cabinet ministers with no hierarchical connotations, will surely rankle with the left-out seniors. Another MLA, B Sriramulu, who was widely being talked about as a potential deputy CM at the time of assembly elections last year, has also been left out of these title enhancements.

The idea of having a deputy CM makes sense when he is clearly No 2, or when the deputy is from a coalition partner, and thus invested with real power. But when the deputies are merely being humoured with higher titles, as is the case in Andhra Pradesh too, where Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy created five deputy CMs, it is not clear what the purpose is beyond short-term ego massage. Even in one-man shows like Arvind Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party, 20 posts of parliamentary secretary were created to invest ordinary Delhi MLAs with an adequate sense of self-importance. When you have 67 MLAs in an assembly of 70 and only seven cabinet berths to offer, this kind of title creation may be of some help.

In Karnataka, though, the creation of three deputies to the CM is a sign of political weakness, not strength. While this may not matter when the BJP is all-powerful at the Centre, and dissonance between the two opposition parties – the Congress and Janata Dal (Secular) – is preventing a gang-up against Yediyurappa in Karnataka, over the long term this is a sure way to create more instability. Nothing harms a power structure more than by efforts to make it over-complicated or diffused. In less than six months, Yediyurappa will probably face discontent and dissidence in his own party, more so if he is seen as a passing phase, given his age.

One can understand that the BJP is torn between the horns of a dilemma in dealing with Yediyurappa: he is the man who built the party in Karnataka and also the current embodiment of Lingayat power, but his age and limited vision do not augur well for the party’s future. The party can neither deny him his importance, nor empower him so much that he causes long-term damage to the party’s growth in the BJP’s only southern redoubt.

The ideal way to sort out the issue would have been to use the fall of H D Kumaraswamy’s government a month ago to call for early polls, where there would have been a reasonable chance of the BJP obtaining a full majority on its own. Given Narendra Modi’s popularity after the Lok Sabha win and the party’s growing influence in non-traditional areas of growth, the BJP could conceivably have done better than in 2018.

A full majority would have given the party the courage to choose someone other than Yediyurappa for the top job, or work out an arrangement where he leaves voluntarily after a year or two at the helm, making way for a younger successor.

Now, the party has no option but to learn the hard way whether the messy compromise engineered in Yediyurappa’s ministry will somehow work out politically, or end up bringing the ministry down if some assembly by-elections end up delivering reverses to the party. Dissidence will bloom if Yediyurappa does not get another 10 seats from the byelections necessitated by the disqualification of those who ditched the JD(S)-Congress coalition two months ago.

D-Day is not too far away.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest