Politics

Veer Savarkar: The Man And Mission Beyond The Mercy Petitions

- Analysing Savarkar’s mercy petitions without looking at his life before and after them would be gross injustice to the freedom fighter. It would also be a thoroughly dishonest approach to evaluate the life of a historical personality.

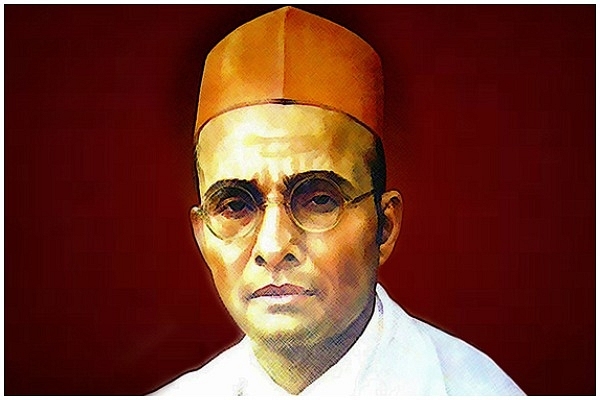

Veer Savarkar.

Every year, on the birth anniversary of Veer Savarkar, columnists and editors dig up the clemency petitions written by him. Their line is that Savarkar capitulated to the British and hence cannot be considered as brave or “Veer”.

Though the false propaganda about the clemency petitions of Savarkar has been busted many times already, it needs to be called out this year too as it has resurrected ritualistically. It also provides us with an opportunity to delve deep into the contributions Savarkar made to India’s freedom struggle in his own way, fortified in a steely silence of secrecy.

Savarkar In Andaman

Savarkar entered Andaman prisons in 1910 with a badge marked ‘D’ for dangerous. There he was specially targeted and subjected to cruelties. Every time there was a disturbance, Savarkar was punished. It was clear that the British government did not want him to leave the prison alive. Yet Savarkar endured all that. But he never believed in rotting in the cell either while he could do valuable work for the freedom struggle by getting himself free. He did sign the clemency petitions. He, at the same time, also appealed for the freedom of other prisoners. Those who quote selectively almost always never quote this passage from his ‘clemency’ petition:

If the manhood of the nation be allowed to phase glories and responsibilities of the empire with perfect equality with other citizens of it, then Indian patriots of all shades and opinions can conscientiously feel that burning sense of loyalty that one feels for one's motherland. I also beg to submit that nothing can contribute so much to the widening and deepening of the sentiment of loyalty as a general release of all those prisoners who had been convicted for committing political offences in India. With my exception, let all the rest be released. Let the volunteer movement go on and I will rejoin in that.

Denigrating Veer Savarkar always involves half-truths, sometimes literally. For example, in The Week, Niranjan Takle, trying to show Savarkar as having submitted to the British, writes: "For the last five years, his behaviour has been very good. He is always suave and polite,” reads the report. But what he does not tell his readers is that the entire line in the report is actually a negative observation on Savarkar by the government. It reads: "He is always suave and polite but like his brother, he has never shown any disposition to actively assist Government. It is impossible to say what his real political views are at the present time."

In fact, after his 1913 petition, his punishment record in the prison was not exactly that of a person whose will was broken. Here are some samples of punishments he underwent in 1914:

- 8th June 1914: Absolutely refusing to work. Seven days standing handcuffed

- 16th June 1914: Absolutely refusing to work. Four months chain gaug imposed.

- 18th June 1914: Absolutely refusing to work. Ten days cross bar fetters imposed

Dhananjay Keer, the official biographer of both Veer Savarkar and Dr B R Ambedkar, points out that ‘during the war period Savarkar made vigorous attempts to effect his release.’ Having studied the petitions of Savarkar to the government, Keer says that the petitions were indirect pressures on the British to run a responsible government in India. However, ‘the authorities knew his intentions and were not at all willing to do so.’

This is reinforced by the observation of the British authorities who saw no change of heart in the ‘clemency’ petitions of Savarkar. Home member of governor general's council Reginald Craddock was the one to whom Savarkar presented his petition. Craddock saw that the petition of Savarkar was 'one for mercy. He cannot be said to express any regret or repentance.' As Craddock explains, Savarkar justified his action by saying that his sending of 20 Browning pistols to Nasik was not for murder 'but in furtherance of a revolutionary movement'. Craddock makes an astonishingly prophetic note in which he recorded that 'the degree to which Savarkar was dangerous or not depended quite as much upon circumstance outside as upon his own conduct in prison, and that no one could say what those circumstances would be 10, 15 or 20 years hence.'

So the question to be asked is, what Savarkar did after he came out of Andaman prison? Did he collaborate with the British or did he contribute to the freedom movement? Savarkar was released with harsh warnings from the British that he could at any time be jailed again and that his Andaman exile could be restarted. So he had to be careful, and careful he was. Nevertheless, he penned books under pseudonyms which became an inspiration for the young revolutionaries.

Was He Eulogising Himself?

One of the malicious charges against Veer Savarkar is that he wrote a eulogising account of himself under the nome de plume ‘Chitragupta’.

Savarkar the historian had seen how the memories of great heroes could be erased by the establishment. He was sure his own contributions would suffer the same fate.

Savarkar was justifiably sure that his life would serve as an inspiration for revolutionaries of the future. So he wrote an autobiography and it did serve the purpose. Durga Das Khanna, an associate of Bhagat Singh, said in an interview in 1976 that when he joined the revolutionary movement, Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev made Life of Barrister Savarkar a necessary reading. The book was clearly anti-British and inspirational to the next generation of revolutionaries. Had Savarkar revealed the identity of the author, he would have been incarcerated by the British. Thus the autobiography was not aimed at self-fame, but to motivate posterity. It was surely more patriotic, riskier and far less narcissist than making one’s own government give one the nation’s greatest award as prime minister.

Apart from writing books under a pseudonym, Savarkar also worked for the liberation of India.

Consistent Campaign For Freedom

As the Second World War broke out, Savarkar also worked to influence the world opinion in favour of India’s Independence. When the then US president Franklin Roosevelt sent an appeal to Adolf Hitler to ward off the colossal danger to civilisation, Savarkar cabled the president that if the latter’s appeal to Hitler was ‘actuated by disinterested human anxiety for safeguarding freedom and democracy from military aggression’ then he should also ask ‘Britain too to withdraw armed domination over Hindustan’. Again, when Roosevelt and Winston Churchill announced the Atlantic Charter on 14 August 1941, Savarkar cabled president Roosevelt on 20 August 1941 asking whether the Charter also covered the case of India and whether the US supported the case for complete political independence of India within a year of the end of the War. The comparison Savarkar had consistently drawn between Nazi occupation of countries in Europe with the occupation of India under Churchill, can be appreciated today in the light of historians uncovering the Nazi-like racist hatred Churchill had for Indians in general, and Hindus in particular.

Even at the risk of being monitored by the British intelligence, he established contacts with revolutionaries overseas, particularly Rash Behari Bose. The latter wrote to Savarkar that ‘every attempt should be made to create a Hindu bloc extending from the Indian Ocean up to the Pacific Ocean’. He desired that Hindu Maha Sabha 'should take immediate steps for establishing branches of Maha Sabha in Japan, China, Siam and other countries of the Pacific ...for creating solidarity among the Eastern races.' The correspondence reflected a parallel attempt to liberate India. On the advice of Savarkar, Rash Behari Bose wrote a letter to Subhas Chandra Bose on 25 January 1938 informing him of the activities of Indian revolutionaries under the banner of India Independence League in South East Asia. Savarkar was the one whom Subhas Chandra Bose met before he left India in disguise. Earlier, on 22 June 1940, Savarkar had informed Subhas Chandra Bose about the activities of Rash Behari Bose.

Savarkar’s strategy was two-fold. He tried to help India gain all the advantages the British government offered through any constitutional means. Consequently, the Hindu Maha Sabha became a part of the Viceroy’s Executive Council. And it was this participation that ensured the United Nations addressed the discrimination against the Indians and ultimately apartheid in South Africa. It was Savarkar who cabled the viceroy to include Dr Ambedkar in the executive council.

In 1942, when Savarkar met Sir Stafford Cripps, who headed the infamous Cripps Mission and spoke about the integral nature of India, none other than Jawaharlal Nehru’s National Herald wrote : “Profoundly as we disagree with his politics, … Savarkar showed the old fire in him, when he took up the thoughtless challenge, thrown to Hindu Maha Sabha by the Government of Bihar and obtained a resounding victory at Bhagalpur. With Sir Stafford Cripps he crossed swords which the former will never forget.”

Indian Army and Indian National Army

Both Dr Ambedkar and Savarkar understood the urgent need to completely Indianise the British-Indian army, failing which it would become disastrous for the nation in the event of Partition. Savarkar also envisioned an army with Indian domination rebelling against the British.

This vision of Savarkar was endorsed and appreciated by both Subhas Chandra Bose and Rash Behari Bose – the revolutionaries behind the Indian National Army (INA). In his message broadcast from Singapore on 25 June 1944, Subhash Chandra Bose praised Savarkar by saying:

When due to misguided political whims and lack of vision almost all the leaders of Congress Party are decrying all the soldiers of Indian Army as mercenaries, it is heartening to know that Veer Savarkar is fearlessly exhorting the youth to enlist in the armed forces. Those enlisted youths themselves provide us with trained men from which we draw the soldiers of our Indian National Army.

In his radio broadcast Rash Behari Bose directly addressed Savarkar:

In saluting you I have the joy of doing my duty towards one of my elderly comrades in arms. In saluting you I am saluting the symbol of sacrifice itself.

It was the INA that played a decisive role in forcing the British to quit India. And Savarkar, despite the looming threats of his incarceration in Andaman again, made a decisive contribution to ensure coordination between the INA founder, the elder Bose and its last leader, the younger Bose.

It would also be useful to sketch the prison life of Congress leaders who came after him; it had become almost a holiday vacation. None other than Asaf Ali had described in his letters how Nehru had his own personal room, which was almost like a small bungalow with curtains in blue, Nehru’s favourite colour, adorning the windows. Nehru did gardening – trying his hand at growing a rose plant. He could write his books. When his wife was ill, without him even having to ask, the British magnanimously suspended his sentence and allowed him to join his ailing wife. Nehru graciously accepted the British offer.

Galileo apologised to the Inquisition. He did not burn at the stake like Giordano Bruno. But that in no way diminishes his status as one who suffered for science and paved the way for the liberation of humanity. What is true for Galileo is also true for Savarkar as vindicated by history.

References:

- Dhananjay Keer, Veer Savarkar, Popular Prakashan, 1950/1966:2012

- Source Material for a History of the Freedom Movement in India: 1885-1920, Government of Indiam 1958

- Dr.S.C.Maikap, Challenge to the Empire: A Study of Netaji, Publications Division, Government of India, 1993

- Ādirāju Veṅkaṭēśvararāvu, Netaji Subhas Bose, the Great Revolutionary, OSS Publications, 2001

- Hari Hara Das, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Great War for Political Emancipation, National Publishing House, 2000

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest