Politics

Why Granting Parole To Terror Accused And Dawood Ibrahim Associate Rashid Khan By Bengal Government Is Patently Wrong

- Khan’s place is behind bars, and for life. Terror convicts cannot, and should not, get parole.

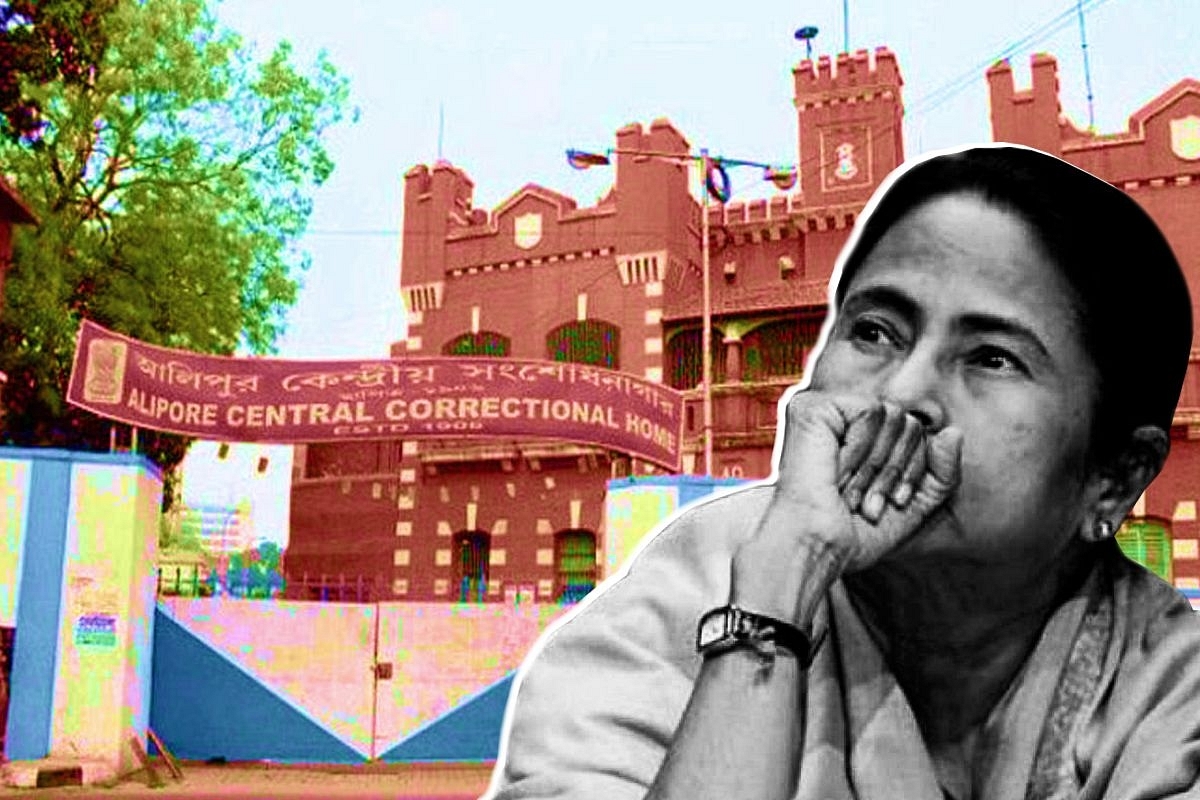

Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee.

Late last week, the Bengal government granted 90 days’ parole to Mohammed Rashid Khan who is, inarguably, the most dangerous terror convict in the state.

Khan, who was known as the satta sultan of Kolkata, was convicted of a huge blast in Bowbazar on 17 March 1993 that left 69 dead, nearly two dozen maimed for life and scores injured.

The blast occurred when a huge quantity of explosives, including RDX, that Khan had kept in his office to make bombs went off accidentally in the wee hours of 17 March.

Khan was an associate of terror don Dawood Ibrahim and was said to be making bombs to target Hindus of Kolkata. The Bowbazar blast came on the heels of the serial blasts in Mumbai triggered by Dawood Ibrahim through his aides Tiger Memon and Yakub Memon.

Rashid Khan, who was reportedly close to some senior leaders of the ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPI(M) at that time, was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment by a TADA court in 2001. The Bowbazar blast was the deadliest in the post-Independence history of Kolkata.

Khan had reportedly confessed to his interrogators that he had planned to plant the bombs made out of his huge stockpile of explosives in different markets and public places in Hindu-dominated areas of Kolkata. The intended explosions were to have been a revenge for the demolition of the mosque built over Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. Had he succeeded, the death toll would have been in hundreds.

Investigations into the Bowbazar blasts had revealed that Khan was close to some front-ranking leaders of the CPI(M), senior police officers and top bureaucrats of the state. He, and his illegal betting racket (satta) had flourished under their patronage.

Alarmingly, soon after he was convicted, efforts got underway to set Khan free. Just six years after his conviction, the then Left Front government under chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee initiated the process for early release of the terror convict.

A life convict can be released after 14 years in prison and the time the convict had spent in prison before his conviction is also counted in the total prison term. Since Khan had been in judicial custody since 1993 (eight years before he was convicted and sentenced), he became eligible for early release in 2007.

The Left Front government lost no time in doing so and got the jail department to recommend his release to the state judicial department. The grounds cited for his early release were as stunning as they were shameful: that he was a religious person who offered namaz five times a day! He was also said to have displayed “exemplary conduct” in prison.

But the Kolkata Police had, in a meeting of the State Sentence Review Board (SSRB), which reviews all life sentences for early release, shot down the proposal. Senior police officers, including the then commissioner of police Prasun Mukherjee, opposed the terror convict’s early release.

It was then left to the Trinamool, which came to power in the state in 2011, to initiate the process of setting Khan free once again. In January 2015, the SSRB headed by then home secretary Basudeb Banerjee approved a list of names of five lifers for early release. No surprises that Khan’s name was on top of the list that had the seal of Banerjee, who was Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s favourite bureaucrat and went on to become the state’s chief secretary.

But the Trinamool government’s plans to set the terror convict free ran into a legal wall. The Supreme Court had, in November 2012, ruled that a lifer convicted under a central Act (like TADA) cannot be released by a state.

Rashid Khan would have been a free man had it not been for the then Kolkata police commissioner Tushar Talukdar who gave sanction in June 1993 for prosecuting Khan under Sections 3 & 4 of TADA. The trial court allowed it but in April 1994, the Calcutta High Court struck down the addition of charges under TADA. But the Supreme Court reversed this ruling in November that year.

Efforts to portray Khan in a positive and benign light started soon after he was convicted. Authorities of Alipore Jail, where Khan was serving his sentence, had repeatedly vouched for his good behaviour. Apart from portraying him as a religious person, the jail authorities also asserted he was obedient and abided by all rules and instructions, was helpful towards others and helped the jail authorities in the smooth functioning of the prison.

He was enrolled into a series of art workshops for jail inmates conducted by eminent artists. Khan’s paintings, amateurish by any standard, have been exhibited outside prison and he was even granted a parole in November 2014 to be present at a six-day exhibition, where his works were displayed.

Khan got good press and was written about as a “soft-spoken”, “gentle” and “well-behaved” man. The Hindustan Times quoted him in this report as talking about one of his paintings of birds: “I have seen enough deaths. Not any more. Let all animals live freely in this beautiful world. Don't kill animals. Let them survive. Let the birds fly because they belong to the sky. Don't keep them caged”.

While laboured attempts to grant Khan an early release have been frustrated by the apex court ruling, the current coronavirus scare came in as a golden opportunity to grant him an extended parole. The Supreme Court had, in end-March, directed states to set up panels to grant parole to prisoners in order to decongest jails and contain the spread of the deadly virus.

The state government seized this opportunity with alacrity and constituted a panel. Khan’s name was, not surprisingly, one of the first to be considered. And unsurprisingly, he was granted a 90-day parole last week and released from prison. He reportedly reached home to a hero’s welcome from his neighbours and family members.

While there may be nothing illegal about Khan’s parole, it is morally and ethically wrong. He is a terror convict whose acts led to the death of 69 people. Had he succeeded in his plans to trigger blasts across Kolkata, many more would have died.

He was a close associate of Dawood Ibrahim, one of the most-wanted in India who is on the payroll of Pakistan and continues to hatch anti-India plots. Khan stockpiled RDX supplied by Pakistan in his office. He wanted to trigger communal riots by killing Hindus.

Khan’s reported ‘good behaviour’ and ‘obedience’ in prison should not matter at all. He broke the law, and did so with a sinister purpose of killing hundreds. He was a criminal, albeit a soft-spoken one, and ran a flourishing illegal betting racket in Kolkata. He was also allegedly involved in smuggling and presided over an army of criminals.

Khan’s place is behind bars, and for life. Terror convicts cannot, and should not, get parole. Their painting skills and readiness to follow prison rules and wardens’ instructions is irrelevant. What should be relevant is their acts of terror.

There is no guarantee that Khan will not re-establish contact with Dawood Ibrahim now and hatch plots targeted against the country and against Hindus once again. There is no guarantee that he will lead life as a law-abiding citizen instead of getting back to his old criminal ways.

That is why releasing Khan on parole was a grave error. Khan’s intended blasts would have extracted a toll much higher than the coronavirus perhaps will. Many say that the accidental explosion of the RDX he had deliberately stockpiled killed much more than the official count of 69. It destroyed countless lives and families.

Hence, irrespective of the deadly coronavirus, Khan should have stayed in prison without parole and that should be his address till his last breath.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest