Science

For The Love Of Birds: India Takes Stock In Honour Of ‘Birdman Of India’ Dr Sálim Ali

- 12 November marks the birth anniversary of Dr Sálim Ali, the 'birdman of India'.

- A bird survey is conducted every year around this date to honour him.

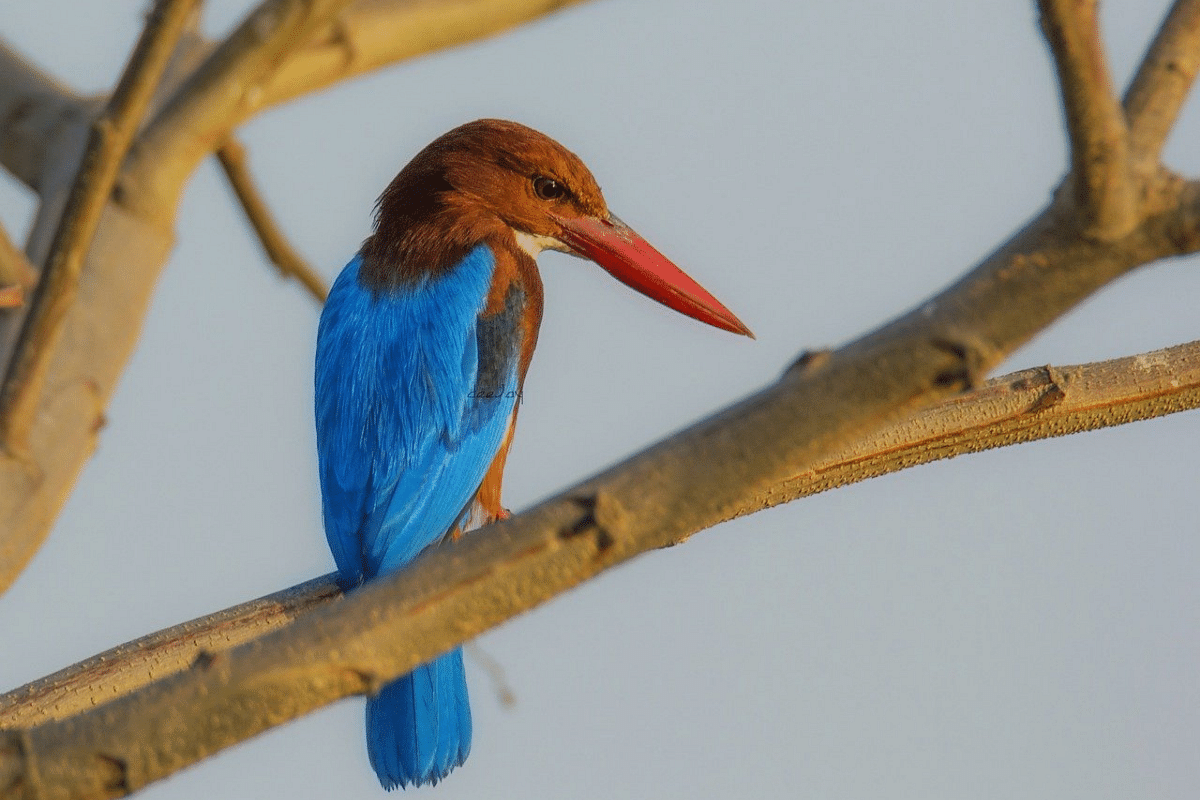

Image by Dishan Jeremiah from Pixabay

Every year in the vicinity of 12 November, the birth anniversary of the ‘birdman of India’ Dr Sálim Ali (1896-1987), India takes stock of its birds in an unofficial census. A call goes out around this time signalling the start of the “Sálim Ali Bird Count” and people with an interest in birds respond by migrating to nature for the simple act of watching and counting birds.

In 2020, the bird count commenced on 5 November, but, unlike in the years past, it has lasted more than a week and will close out on 12 November.

“When they started the Sálim Ali Bird Count, the counting would be done on two days, typically Sundays, since that’s when people could go out and watch,” Mittal Gala, programme coordinator at Bird Count India, tells Swarajya. “But this year, the activity is scheduled in such a way so as to coincide with Pakshi Saptah (Bird Week), which lasts eight days.”

Pakshi Saptah is a birding event held annually in Maharashtra. Brought to life by the Maharashtra Pakshimitra, it marks the birth anniversaries of both wildlife conservationist and Marathi author Maruti Chitampalli and Dr Ali, and hopes to spread the joy of birds among the public.

The Sálim Ali Bird Count, on the other hand, is a child of Bombay Natural History Society, with which Dr Ali enjoyed a long and close association in his lifetime, and is supported this year by Bird Count India, Maharashtra Pakshimitra Sanghatana, and Indian Bird Conservation Network.

Besides the wider window for watching and counting birds, and this being a pandemic year, little else has changed for the counting exercise this year.

The guidelines say that interested birders have to watch and count birds within the 5-12 November period. They can make their observations from anywhere, such as from their home balcony, but are encouraged to visit the nearest ‘Important Bird and Biodiversity Area’, water body, or wooded patch on at least one of the days to watch and count birds for an hour.

It is recommended that the activity is pursued early in the morning, since birds go quiet as the sun traces its familiar arc in the sky over the course of the day.

After the observations are noted, participating bird-watchers have to record their sightings digitally on the eBird and/or Internet of Birds mobile applications. The lists have to be uploaded not later than 10 December (more details here and here), after which an analysis takes place followed by the release of data by mid-month.

It would be interesting to know whether the number of participants is higher in a year when individuals have gone in search of new hobbies on account of the Covid-19 lockdowns.

With her experience interacting with the birding community, Gala thinks more people have taken to bird-watching but is not sure about the participation level in the counting exercise. “Since the pandemic, the number of people getting into birding has definitely increased, but we don’t know yet if the documentation of birds has increased.” We will know in December after the release of data.

Some of the seasoned birding communities have gone about watching and counting birds as they do through the year. Port Blair-based “Andaman Avians Club” is a fine example.

“Bird-watching has been good so far. The migration of birds has begun and we are seeing that. The bird count is less, mostly due to rain, but we have identified a good number of species,” Bivash Chandra Kirtania, the general secretary of the club, tells Swarajya.

The Andaman Avians Club is keeping it simple. They select areas in advance where club members can congregate at a set date and time. Once they are there, they split up in groups and set off on trails watching and counting birds for 45-90 minutes before heading back.

“Internet connectivity is bad in our field trips. So after the closure of the activity, we get back and upload our listing to eBird,” Kirtania says.

The “eBird” platform is a vital cog in the bird-watching wheel. It is a collaborative biodiversity online space established and managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The website reveals that its users upload upwards of 10 crore bird sightings every year on their platform and the participation is increasing roughly by 20 per cent every year.

Extensive data such as that available on eBird has become the basis for determining the status of birds in different places. Just earlier this year, an assessment of the distribution and conservation status of 867 birds in India, based on data supplied by 15,500 bird-watchers, led to the comprehensive ‘State of India’s Birds 2020’ report.

One of the important findings in the document was that 52 per cent of bird species were in decline over the past decades and about 12 per cent required immediate attention. Insights such as these can get the ball rolling for appropriate research and policy action centred around biodiversity conservation.

The citizen-science counting exercises in particular can potentially offer researchers, conservationists, and hobbyists a snapshot of bird species presence in various areas. Comparing these annual numbers over the years can not only enable the monitoring and conservation of birds but also provide a fair assessment of the state of nature.

After all, birds can do more than call or sing; they can indicate the health of our natural environment. To know that though, we would have to listen.

Birding communities like the Andaman Avians Club are doing just that. “On average, we are out in the field about three to four days a week,” says Kirtania. “We get together in the morning and go for personal (single person) or group birding on different trails and make our observations.”

Kirtania says he likes to listen to the calls and watch the behaviour of birds.

In the past, observations about birds would get lost in the pages of history, as physical notebooks were the only choice. That is no longer the case today.

“Back in the day, birders would go out and watch birds and write down what they saw in notebooks. This information would then remain in the notebooks. But now, bird sightings can be recorded on digital notebooks which are accessible to anyone,” Gala says.

One hopes that this spirit of collaboration can swell up birding clubs and communities across the country and spread the love of birds among the uninitiated. Now more than ever, there is a need to build a deeper connection with nature. We can let birds be our guide.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest