Science

Haldane, Caste And Hinduism: A Closer Look

- From 1917 till the end of his life, the JBS Haldane's approach to Hinduism was shaped by one thing—his quest for Satya.

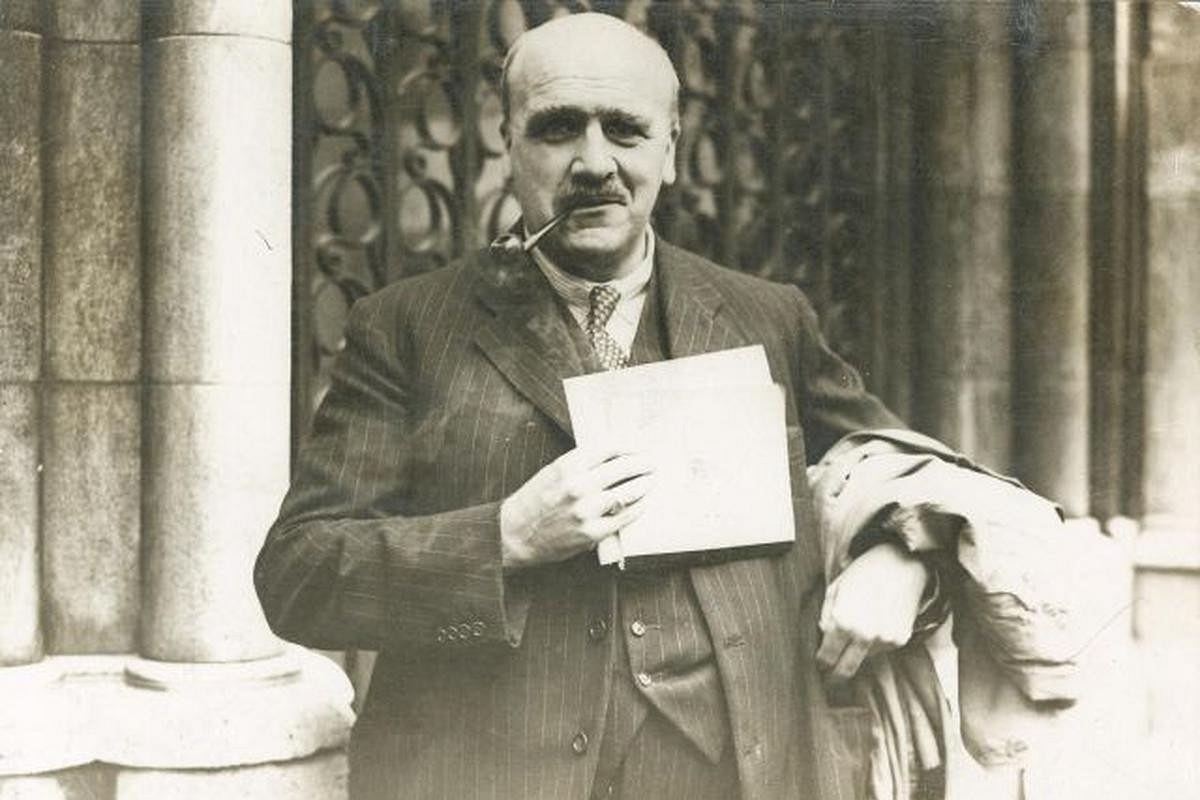

JBS Haldane

Can a person combine an uncompromising search for both the fundamental truth underlying all existence and for making the society a more humanistic one with lesser suffering than the present?

Where would such a search lead a person?

If one has been living in the 1940s, the answer would have been obviously, Marxism.

Marxism has the promise of both answers - answering the fundamental mystery of existence through dialectical materialism and providing a solution for human suffering through the dictatorship of the proletariat which would finally usher humanity into an utopia where the state would wither away. And it places itself in the tradition of Christianity and Islam as 'the only truth'.

In this context, let us examine a life of a scientist—a polymath committed to finding the secrets of life and existence and also equally committed to a better world where human condition would vastly improve.

Where did that quest lead such a personality?

I - JBS Haldane - 'a potential Muslim not a potential Hindu'

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (1892-1964), British-born Indian scientist, led a colourful life, ever-adventurous of the cerebral kind. An evolutionary biologist, physiologist, biochemist and statistician, he was a polymath. He was one of the architects of modern evolutionary theory.

In 1917, Haldane came to India. He was barely 25. His views were typically that of a British colonial, military man.

He wrote:

His observation of Indian society was negative:

He compared Hinduism with Islam:

The above is a typical colonial assessment of Hinduism and not different from that of a Winston Churchill or a Beverley Nichols.

Essentializing Hinduism with caste, they admired the 'egalitarian' Islam. Churchill was at one point ready to embrace Islam or so, thought his near ones. Haldane's biographer Ronald Clark remarks similarly that Haldane 'was a potential Muslim, not a potential Hindu.' (p.50)

II- From 'a Party-Scientist' to 'Party or Science?'

In 1930s, Haldane started getting attracted to Marxism. During this period, in a rather condescending way, he was looking at the deeper philosophical aspects of Hinduism.

Couched in Hegelian terminology and gravitating towards Marxist materialism, he diagnosed an unfortunate 'tendency to identify the absolute—i.e. the universe considered in its mind-like aspect—as in some sort an equivalent of God'.

Though he himself could not 'see the cogency of that view' it still provided 'a fairly satisfactory emotional substitute for Theism.' He could easily see the similarity between this and the Hindu 'Brahman' but cautioned that such a philosophical religion could still worship various Gods.

He was also confusing Brahma the Puranic creator with Brahman the principle. ('The Inequality of Man and Other Essays', 1932:38, pp. 184-5)

Though in an accelerated fall towards Marxism, he admired Gandhian Satyagraha. The official Party line (both Communist Party of Great Britain and that of Soviet Union) was that salt Satyagraha was actually 'calculated to help the triumph of colonial power in India.'

Haldane supported Salt Satyagraha refreshingly from a physiological perspective:

In 1942, Haldane officially joined the Communist Party.

Throughout the 1940s though, his views on India slowly changed. The evolutionist underwent his own inner evolution. Writing copiously for Daily Worker the organ of CPGB, he became the Party's voice of science.

Then came the Lysenko crisis.

Under Stalin's patronage, Lysenko, a plant-breeder castigated genetics as Bourgeois science. Ideological commissars agreed. Information started leaking that the geneticists were persecuted in Stalin's USSR. Geneticists were arrested, asked to recant or jailed, tortured and executed.

Haldane was torn between his commitment to party and science. Within party circles he argued against what was happening in the USSR to the geneticists. Outside, including in an infamous BBC debate, he half-heartedly tried to justify what was happening in the USSR.

This included the death of Nikolai Vailov, personally known to Haldane.

Haldane thought Vavilov had actually been freed and died working in Arctic and stated so in a BBC debate. Haldane even went to the extent of calling the brilliant scientist Vavilov as a 'plant-breeder'. Yet, the Party was not pleased with his half-hearted defence.

Finally he had to break with the party and denounce the USSR. By this time the Soviet Union had gone to the extent of characterizing genetics as Bourgeois science and even denying the existence of genes. Teaching genetics was banned.

In 1948, Haldane quit the party.

In a detailed study of this painfully fascinating phase in the history of genetics, Prof. Diane B. Paul concludes thus:

Yet another problem surfaced. Reports of atomic espionage by politically influenced or financially favoured scientists were coming out in the West. Haldane himself was coming under increased scrutiny of British intelligence. Also questions were raised in political circles as to why a Communist scientist like Haldane had access to important researches.

Haldane could neither go to the USSR nor live a life of freedom in England.

Meanwhile he had started admiring Indian culture more and more. He was also observing keenly the developments happening in Indian society. Here are a few glimpses into the evolutionary trajectory of of his views.

III-An Evolutionary Biologist's Evolving Views on Hinduism

Even a few years before migrating to India he believed in the historical validity of Marxism. But he was increasingly understanding the dynamic nature of Hindu Dharma.

Still categorizing Advaita as 'absolute idealism' as opposed to scientific materialism though, he considered the latter to be true:

In 1956 writing about 'miracles' Haldane wrote:

One should note here how Haldane, within a span of two years, had gone from the possibility of Hinduism succumbing to Marxism, to criticizing the narrow worldview of 'Naturalism' which he thought his scientist friends, including those from India, had. Even his admiration for Nehru was partly because the Prime Minister practiced Yoga and mainly because he was a rationalist. This admiration would later diminish.

In 1956 he delivered the Huxley Memorial Lecture. He astonished his audience with a call for using 'Hindu anthropology.' The talk, worth quoting in detail, is relevant even today for the formation of Hindu social sciences.

The Hindu system he expressed was based on the work of Nirmal Kumar Bose (1901-1972), Cultural Anthropology. Haldane continued:

Of course, his way of presenting the Purusharthas could be challenged. But the more important point to be noted is his formulation of a Hindu framework for social studies without the usual obsession with caste system.

He seemed to have realised clearly that the principles for longevity of the civilisation lay elsewhere, and not in social stratification. With an extraordinary insight he pondered over the question of discovering these elements—- including what he called Mokshadharma— in non-human animal life

Haldane had his own misgivings about Jan Sangh as a religious orthodox party. Yet it was the Jan Sangh ideologue Deendayal Upadhyaya who took forward the format put forth by Haldane.

Upadhyaya's 'Integral Humanism', while mostly ignoring jaati-varna, concentrated on Purusharthas.

In 1957, Haldane announced his decision to come to India for a talk to the rationalist association. It was later published as A Passage to India.

He still held some inaccurate views. For example he said that Gandhi was assassinated because he opposed caste and his assassin was a 'traditionalist' though Godse had been an anti-caste activist.

Despite Haldane's 'sneaking sympathy for Brahmins' he also held a non-negative view, but not an acceptance, of 'Mr. Naicker's movement' in southern India.

But his earlier view on caste system had changed. He saw the 'caste system' as more dynamic. Surely it was discriminatory. He compared it with similar elements in British society:

Now he was more a 'potential Hindu' and rejected Islam categorically. He told the members of the rationalist society this:

With much enthusiasm he joined Indian Institute of Science.

In 1957 Haldane gave the famous Patel memorial lecture. The title he chose was 'Unity in Diversity.' Among other things he pointed out that diversity of various components in a system is healthy when each of these components could perform their Swadharma. Haldane concluded his lecture by pointing out the unity of life and stated:

While many know about physicists being fascinated with 'Eastern wisdom' not many know about the fascination biologists had for Hinduism.

The scientist whom Haldane mentioned was Bernhard Rensch (1900-1990). An evolutionary biologist, he started with belief in transmission of acquired characters driving evolution. Soon he was convinced of Darwinian selection and like Haldane was one of the chief architects of 'the modern synthesis' - between genetics and natural selection.

He did his field work in India and Indonesia and his non-dualist philosophy of biology was influenced by Upanishads, Spinoza etc. He wrote:

Into the 1960s, Haldane was increasingly disillusioned with the way Nehruvian State had lovely words for science but little to show for them. It combined the inefficient elements of both British and Soviet systems to become their worst caricature.

Nehru initially considered Haldane a prized catch. He even politely answered a few of his letters. Later, he ignored them.

Finally his conflicts with Mahalanobis at the Indian Institute of Statistics made Haldane move to Bhubaneswar to establish the Genetics and Biometry Laboratory with the support of the then 'Orissa' state government.

Indian statistician Mahalanobis was originally Haldane's good friend, instrumental in bringing him to the Statistical Institute. Haldane's own inability to fit into institutions also was a factor in move away from the IIS.

Alarmed at a new caste system that Nehruvian State was creating, he compared it with the old system and wrote:

Dr. Krishna Dronamraju (1937-2020) was a brilliant geneticist. When J.B.S. Haldane came to India in 1957 he wrote to him and joined him as a PhD student. Then he became his colleague in research and was closely associated with Haldane till the latter's death in 1964.

In 1985, he wrote about the life of Haldane.

Benefitting from his close association with Haldane the book naturally focussed on his life in India. The book Haldane: The Life and Work of J.B.S.Haldane with Special Reference to India (Aberdeen University Press, 1985) was reviewed by another scientist, a bio-chemist and virologist, N.W.Pirie in Nature magazine.

In this critical review Pirie opined that Dronamraju had overstated the affinity JBS Haldane had for Hindu Dharma. He wrote:

Prof. Dronamraju, also a prolific science writer wrote his last book in 2017 which too was on Haldane. Here he brought out a very interesting incident in Haldane's life :

The view of both Haldane and his wife Helen Spurway with regard to evolution and Hinduism is given in another article. From his 1917 prudish aversion for the worship of so-called 'reproductive organs' by which he meant Shiv Linga, to his near religious rapture before the Shiv Linga at Kashi, the change had been phenomenal.

In conclusion, from 1917 till the end of his life, the approach to Hinduism for Haldane was shaped by one thing - his quest for Satya. He placed that quest above everything else - from his colonial biases in 1917 to party affiliation in 1940s to the end of Indian days. His life is the embodiment of the Upanishadic message to humanity - असतोमा सद्गमय !

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest