World

CCP: A Century Of Expansionism

- A reading of the CCP over the last 100 years makes it plain that unquestioned and total dominance of China is central to its worldview.

(Flickr)

While I pen this essay, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has finished a century-long journey.

CPC, yes, the Chinese Communist Party that was officially founded on 1 July 1921 by Chen Duxiu, Li Dazhao and 15 other representatives.

It might seem interesting that while communism did not survive handsomely anywhere else on the planet, it has been surviving for more than a century in the Peoples Republic of China.

Apologists often hail communism as the most appropriate socio-political system, and China always pops up as an example and case study. But an objective look at the history of the party and its progression presents a reality that would be disappointing for the apologists.

Tianxia

China has always been expansionist by nature. It has had a trait of expansion since the period when India was witnessing the end of the Indus-Saraswati civilisation.

The phenomenon is evident in the records from the era of the Zhou dynasty in the 11th century BCE. The same ideas are reflected in the works of Sun Tzu, a Chinese General around the 6th century BCE.

Eventually, the idea of global domination emerged as the notion of Tianxia which means: ‘all under heaven. According to this worldview, the Chinese emperor had the right to rule the entire ‘space under heaven’.

This piece is not to present details about Tianxia, but I chose to introduce the idea because it is core to the larger worldview of the Chinese state.

China was defeated in the Second Opium War and with the signing of the treaty of Tianjin, China had to begin to refer to Great Britain as a "sovereign nation", equal to itself.

Tianxia appeared to be vanishing.

The First Sino-Japanese War also saw China being defeated. It is said that Tianxia collapsed completely after this.

By the end of the 19th century, China had begun rendering ancient ideas in different ways though. The Chinese Ambassador to Great Britain, Xue Fucheng, brought traditional Hua-Yi distinction (Sino–barbarian dichotomy) in the Tianxia worldview and replaced it with a Chinese-foreigner distinction.

Republic of China

The Chinese Revolution, 1911, had brought an end to the imperial rule of more than two millennia. The revolution culminated in a decade of agitation, revolts, and uprisings.

The Qing dynasty had struggled for a long time to reform the government and resist foreign aggression, but the programme of reforms after 1900 was opposed by Manchu conservatives at court as too radical and by Chinese reformers as too slow.

Finally, from October 1911 onwards, China saw extensive uprisings, and on 1 January, 1912, the Republic of China came into being.

In my opinion, this was the time when Tianxia was breaking and China was appearing extremely weak in front of foreign powers. Till a few decades back, they lived with the traditional Hua-Yi distinction (Sino–barbarian dichotomy) and now Yi seemed to be taking the upper hand.

Post-World-War I

As a party, the CCP started with a small membership of only 50 in 1921. While the CCP was just sprouting, the Kuomintang (KMT) party was in power at the time in China. KMT was given military and financial aid from the USSR on the condition of allying with the CCP based on the agreements on 12 April 1923.

With time, rifts became quite common in terms of control and power.

The death of Sun Yat Sen in 1925 intensified the issue. Chiang Kai-Shek became the leader of the KMT in 1925 and saw the emerging communist group as a threat to his power. And then came the Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927.

It was a violent suppression of the Communist Party of China (CPC) organisations and leftist elements in Shanghai by the forces of General Chiang Kai-shek. A full-scale purge of communists continued in all areas under their control, and violent suppression occurred in Guangzhou and Changsha.

The Era of Civil War

General Mao Zedong was the man in focus. In July 1927, the CPC formed the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army under his leadership. They organised a massive uprising against the KMT, but Mao’s Red Army was forced to retreat to the mountains.

The organizational structure of the CPC was nearly destroyed. But Mao was determined about what he wanted to do. By 1935, Mao became the CPC's informal leader and began to centralise power and pass controls beneath him.

His ways were much different from the conventional Marxist-Leninist ways which indeed paved the way for the long-lasting existence of the CPC.

In due course, came the Second Sino-Japanese War and WWII. The conflict between the CPC and KMT ceased. The CPC and the KMT came together to fight against Japanese aggression.

This era brought a big difference. The CPC utilised this time to expand its influence by gathering support from ordinary people, precisely speaking, peasants, at the expense of its current ally, the KMT.

Japan’s surrender in WWII saw CPC and KMT dragging China into a Civil War which continued till 1949. As the war began, KMT had thrice the number of soldiers than the CPC.

The USA and Japan came out as an ally to the KMT. On the other hand, USSR, Chinese rural population and students came out in support of the CPC.

The sentiment of common rural residents helped the reinforcements of CPC. The anti-Japan and anti-USA sentiment too helped CPC strengthen its ground. It must be noted that till now CPC had not brought any extreme communist political changes and had gained the support of the people.

By the last month of 1949, KMT had collapsed completely in Mainland China.

On 1 October 1949, Mao declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

With the end of the civil war, the KMT retreated to Taiwan, where in 1950, Chiang Kai-Shek established the Republic of China.

The Single Ruling Party

After having risen with people’s support, Mao began to put in communist policies in practice in a philosophy that would ultimately be called Maoism.

His communist reforms had no regard for individual life. A few of his important initial policies were:

1. Land Reforms: Redistribution of wealth amongst the people by taking away land from the current owners and dividing it up equally. Ironically, this was implemented through selected landlords.

2. Campaign to suppress counter-revolutionaries: Public executions, mainly targeting former KMT officials, former employees of Western companies, businessmen accused of causing market turbulence, and disloyal intellectuals.

3. Campaign to reduce opium addiction: This nearly eradicated the drug problem from society but 10 million drug users were forced into treatment, and drug dealers were executed.

4. Hundred Flowers campaign: To start with, people were encouraged to share their criticisms of the CPC government. Just after a few months, Mao reversed the policy, and around half a million people who had criticised the government were persecuted.

5. Mao’s First Five-Year Plan to quickly industrialise China: China was a predominantly agricultural country when it turned communist. It was the support of peasants that had strengthened the CPC. But “The Five Year Plans” were meant to heighten China’s industrial potential, which ended up bringing a heavy toll on ordinary people. They had to make extraordinary efforts to attain the targets of the five-year plan. Failing the target meant execution.

Many other draconian measures ultimately were focussed to centralise power in the hands of the CPC or Mao.

In the era of the 1960s-70s, CPC disagreed with the USSR on grounds of ideological issues. To shape communism in the mould of globalisation, USSR was softening its diplomatic approach while CPC under Mao kept hardening its stance against the Western world. Mao tried to morph Marxism based on the unique characteristics of Chinese history and culture even though this paradox was quite complex.

In Mao’s version of Marxism, capitalists and the traditionalists were to be rooted out, for, he believed that they were sabotaging China’s rise to world power. Mao hoped that China would accelerate industrial production and complete the socialist revolution with the removal of such elements.

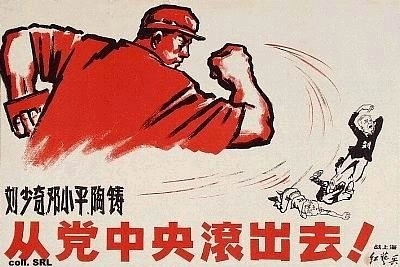

Cultural Revolution & Opening of Economy

In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution intending to unify the country under a communist vision based on unconditional trust in Chairman Mao.

Alike his other communist authoritarian counterparts, he too went on to use violence as a tool to silence anyone who appeared as a threat.

This regime of violent struggles across China brought terrific unrest. Millions of people, especially intellectuals — were persecuted. They suffered a wide range of abuses, ranging from public humiliation, seizure of property, and, on occasion, execution.

Youth from urban areas were forced to stay in rural areas as part of Mao’s campaign to accelerate food production (Down to the Countryside Movement).

Historical and cultural sites were destroyed. Horrifyingly, the remains of previous emperors of China were even removed from their graves and burned.

The sadistic phase of the paradoxical Cultural Revolution began to be quite inactive from 1969, but the campaign did not officially end until Mao died in 1976.

Deng Xiaoping became the next "paramount leader” in 1976. Looking at the shifting geopolitics, he opened China to the world's markets and began to reverse some of Mao's policies.

In Deng’s opinion, and rightly so, a socialist state could use the market economy without being capitalist. Although the policy change generated significant economic growth, the new ideology was not very well taken to by the Maoists.

They wanted political and social liberalisation as well along with that of the economy. The internal unrest became prevalent and then came the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

These were a series of political demonstrations for democracy led by students in Beijing, which reflected the anxieties about the country's future.

The students said that Deng’s reforms had led to economic growth, but they benefited only a few and many still lived in poverty. The student protestors also asked for greater democratic participation and accused the government of corruption.

To curtail it, 300,000 troops were sent, which later led to the killings of thousands of demonstrators and bystanders.

Finally, changes were made to address the protestors’ demands. By the early 1990s, the notion of a socialist market economy, an economic system with some private ownership of state industries, had been introduced.

In 1997, Deng's beliefs (Deng Xiaoping Theory), were embedded in the CPC constitution.

Xi Jinping

Xi became CPC's leader in 2012. President Xi reversed moves toward collective leadership, in favour of centralising his power. Xi has always emphasised the importance of communist political thought in Chinese culture and his approach is popularly known as “Xi Jinping Thought.”

It is part of the Chinese Constitution. Interestingly, the most popularly downloaded smartphone app in China is Xuexi Qiangguo, which translates to “Study powerful country.”

It teaches “Xi Jinping Thought.”

The whole vision of the CPC has largely been based on expansionism, wherein paramount leadership is a big factor. They rose to power on anti-imperialistic sentiments, supported by peasants and students and took quite a long time to bring in communism-based reforms.

The current pandemic situation is also alleged to be a part of their expansionist ideologies. Perhaps, this subject can be dealt with in some other essay with more details.

Support Swarajya's 50 Ground Reports Project & Sponsor A Story

Every general election Swarajya does a 50 ground reports project.

Aimed only at serious readers and those who appreciate the nuances of political undercurrents, the project provides a sense of India's electoral landscape. As you know, these reports are produced after considerable investment of travel, time and effort on the ground.

This time too we've kicked off the project in style and have covered over 30 constituencies already. If you're someone who appreciates such work and have enjoyed our coverage please consider sponsoring a ground report for just Rs 2999 to Rs 19,999 - it goes a long way in helping us produce more quality reportage.

You can also back this project by becoming a subscriber for as little as Rs 999 - so do click on this links and choose a plan that suits you and back us.

Click below to contribute.

Latest