World

Post-Pandemic, China’s Belt And Road Initiative Is A Mess

- Estimates suggest that over 60 per cent of China’s Belt and Road Initiative loans are now to countries in critical debt crises, up from a mere 5 per cent in 2010.

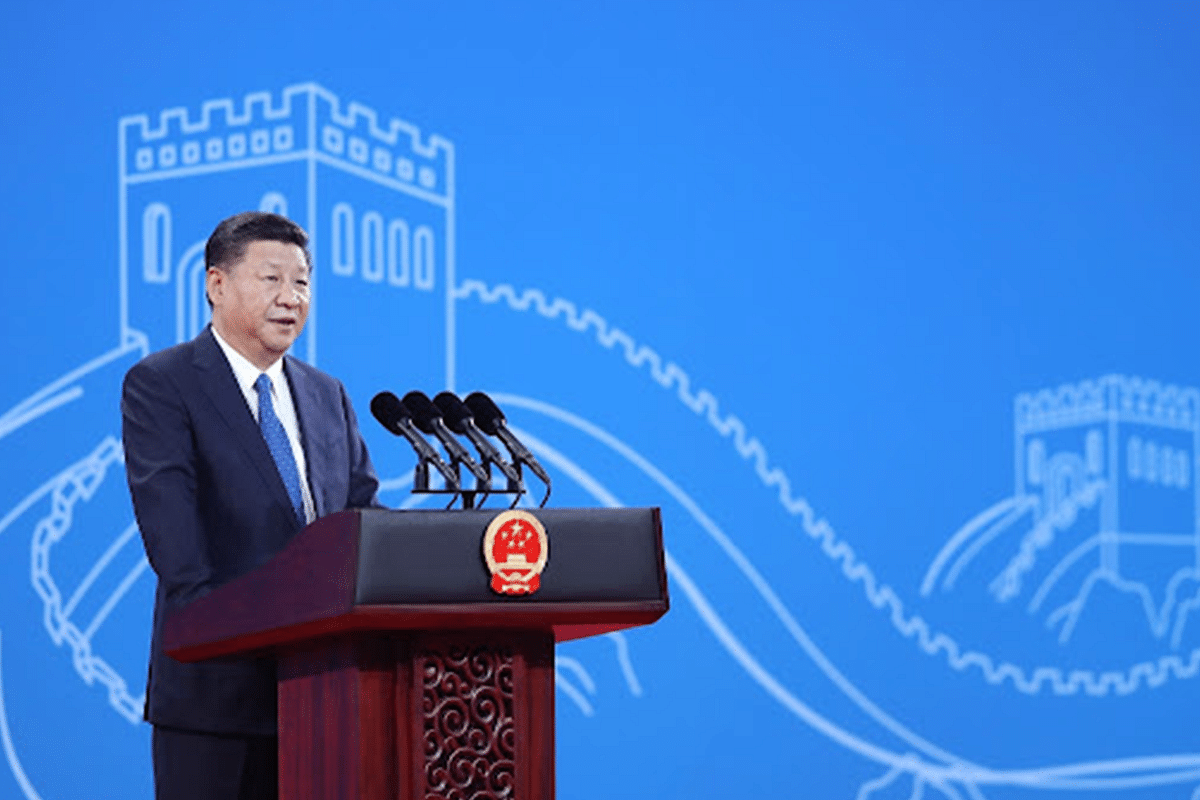

Chinese President Xi Jinping (Lintao Zhang - Pool/Getty Images)

Where is China’s Belt and Road Initiative, almost a decade after it picked up steam? Ten years after President Xi Jinping took over the reins in Beijing and mere weeks before the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, the focus is on the Belt and Road initiative as reports of debt restructuring emerge.

Post-pandemic, Beijing has been busy engaging several smaller economies given the inflated debt crisis, hidden debt reported from over forty countries where the money they owed to China was more than 10 per cent of their gross domestic product.

The debt crisis has been aggravated by the lower and middle-income countries’ woes during the pandemic. Sri Lanka, for instance, has been negotiating to restructure its long-term debt with China.

Pakistan’s infamous CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor), with an investment in excess of $60 billion, has been plagued by protests and delays. Earlier this week, Ecuador restructured debt worth $3.2 billion with China. Between 2020 and 2021, loans worth $52 billion were negotiated.

However, the renegotiations and debt restructuring are not directly due to the pandemic alone. More than 100 loans in Sub-Saharan Africa, 21 in East-Asia and Pacific region, 12 in Latin America and Caribbean region, nine in South Asia, five in Europe and Central Asia, and four in the Middle East and North Africa had already been renegotiated until early 2022.

As per an independent OECD study, of the 148 countries involved in the Belt and Road initiative, 52 had been classified as very high risk, and only one nation was without risks.

Beyond the restructuring, Beijing’s loan buoyancy has also come down in the last two-odd years. The BRI reflects a slowdown in construction and investment already.

In 2020, the investment was around $41.7 billion, $48.9 billion in 2021, and $15.6 billion in the first half of 2022.

When compared to pre-pandemic years, the numbers tell a different story as in 2019, the investment was around $98.4 billion, $119.7 billion in 2018, $173.4 billion in 2017, $164 billion in 2016, and over $100 billion in both 2014 and 2015.

Russia is another unique testament to the downward spiral of the Belt and Road initiative. In the first half of 2022, the BRI investment in Russia amounted to zero. Before coming down to less than $2 billion in both 2020 and 2021, the construction and investment outflow to China was over $5.5 billion on average between 2014 and 2019.

Between 2000 and 2017, the total investment committed to Russia amounted to more than $120 billion. However, the focus has shifted, especially since February and the beginning of the war in Ukraine.

Between 2020 and 2021, the construction under the BRI globally has been around $67.3 billion, as per the data compiled by the American Enterprise Institute.

Until then, it was over $460-odd billion. Since the beginning of 2021, minus the construction, the investment was around $32 billion, compared to $321.73 billion until the end of 2020.

Since 2021, only Philippines, Serbia, Russia, Singapore, Chile, Uganda, Iraq, and Algeria witnessed significant investments in construction projects, some over a billion dollars. Other countries saw miniscule investments, mostly under $500 million.

In the last eighteen months, the BRI investments have also mainly been subdued.

Major investment destinations included Peru (energy, $560 million), Indonesia (logistics, $1.3 billion), Tanzania (energy, $790 million), Chile (transportation, $800 million), Zimbabwe (metals, $950 million), South Africa (metals, $700 million), Saudi Arabia (energy, $4.6 billion), Republic of Congo (metals, $2.5 billion), Ghana (metals, $470 million), Israel (transportation, $1.7 billion), and Iraq (energy, $600 million).

Post-pandemic, China’s Belt and Road initiative is a mess, hit by the double whammy of inflation and slowing growth across the world, especially denting lower-income countries.

Estimates suggest that over 60 per cent of the BRI loans are now to countries in critical debt crises, up from a mere 5 per cent in 2010.

President Jinping, battling slowing domestic growth, can no longer indefinitely employ China’s foreign reserves to equal the West and the IMF. From here, it will all be about how bad it gets, before it gets better, and if it gets better.

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Latest