Bihar

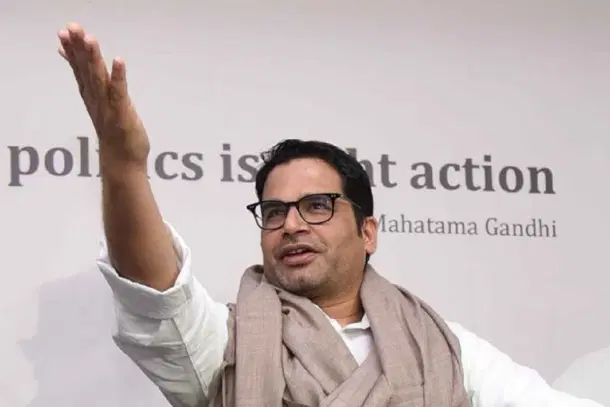

Prashant Kishore Is Wrong: Bihar Cannot Skip 'Factories'

Aditya Bharadwaj

Jul 23, 2025, 11:19 AM | Updated 11:25 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Recently, a clip of the ANI Podcast went viral where Prashant Kishor, the founder of Jan Suraaj, made some absurd claims about Bihar and industrialisation. He claimed that though he wants to stop migration, he does not want to commit to the industrialisation of Bihar.

Kishor then went on to give examples of New Zealand, Singapore, and Finland, claiming that these countries do not have any ‘factories’. He says that the focus should be on improving education and bringing in funds through the service sector.

However, the aforementioned claim does not hold true if some facts are taken into account.

Singapore is a country about half the size of New Delhi with a sixth of its population, lying in the middle of one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. It had the right systems in place that were strengthened by the leadership of Lee Kuan Yew, which caused an economic miracle in the city. Its model is something which cannot be replicated anywhere else.

On the other hand, New Zealand is a mid-sized country with an area almost three times the size of Bihar, while its population is 4 percent of that of Bihar. It became rich because of agricultural and mineral exports that its population could manage due to its extremely low population density of 20 persons per square kilometre. However, even New Zealand’s approach is impractical for Bihar.

Finland, which Kishor cited as having no ‘factories’, is actually an industrial powerhouse leading in telecommunications equipment, heavy machinery, shipbuilding and electronics, having created global giants like Nokia, Kone, and Stora Enso.

So to dismiss industrialisation would be unwise, to say the least.

Why Industrialisation?

It is true that the service sector has contributed a lot to the Indian economy, largely due to the IT services and technology boom from the 1990s onwards. Nevertheless, out of India’s total working-age population, which is 961 million, the services sector employs only about 182 million workers as per the latest estimates from NITI Aayog and the Economic Survey.

Even those numbers may go down due to a variety of factors including saturation of key markets like the US and EU, advancement of AI, margins being squeezed, and increasing competition from Southeast Asia and Latin America.

Additionally, the industry is concentrated in a few cities including Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune, Chennai and NCR. In these circumstances, when growth potential is limited and old clusters have plateaued due to agglomeration, chances of developing new clusters far away from major metropolises are limited.

Hence, even if Bihar wants to channel its energies into developing the services sector, it would be difficult to flourish. On the other hand, industrialisation can become a boon for Bihar.

Research consistently demonstrates that manufacturing has the strongest multiplier effects in the economy. For every job directly created in manufacturing, 2.2 additional jobs are created in other sectors. This doubles the effect of non-manufacturing industries and triples that of modern services.

Thus, focusing on industrialisation is the best way forward to keep Bihar’s young population employed without migrating outside the state.

Additionally, manufacturing jobs are in a way more ‘stable’ compared to service sector jobs. It is much more difficult to move a factory that has been established than it is to move a company offering financial services, due to the high capital expenditure involved in the former.

There are high upfront costs to industrialisation, but these costs can pave the way for profits in the long run.

Prashant Kishor's Misconception on Industrialisation

Kishor’s opposition to industrialisation by citing Bihar’s landlocked status and population density is absurd because no country, large or medium-sized, has ever escaped low-income status by avoiding industrialisation.

Having high population density is actually an advantage for promoting manufacturing-based growth. The city of Hong Kong is an example. It consists of islands and a peninsula with much higher population density that became rich through industrialisation (3000/km² in 1960).

The textile industry became the cornerstone, with cotton spinning emerging as the primary sector in the 1950s as businessmen escaped China following the Communist Revolution. Later, the manufacturing sector diversified dramatically into electronics, plastics, toys, and watches.

By the mid-1960s, Hong Kong became the third-largest textile exporter globally, trailing only Japan and India. Their electronics industry, virtually non-existent before 1959, grew to account for 10 percent of total domestic exports by 1970. The manufacturing sector in Hong Kong later gradually shifted to China as the latter opened up and started its manufacturing journey.

Even the Red River Delta in the north of Vietnam has a high population density of around 1000 persons/km², but it has managed to emerge as the economic engine of the country. It contributes one-third to the national GDP of Vietnam while merely being 4.5 percent of the country’s landmass. Through focused industrial policy and active government support, Vietnam harnessed the human capital in the Red River Delta to push itself out of poverty.

A high population density like Bihar’s also gives it an advantage with respect to having sufficient labour readily available, a big enough market, and opportunities for knowledge spillover and innovation through agglomeration effects.

Another advantage of Bihar’s demographics is that it is extremely young. Seventy percent of its population is below the age of 35, with 58 percent being below the age of 25.

The only disadvantage that high population density brings with it is the high cost of land. But the cost of land is only one factor that plays into the decision-making matrix of industries, which the state can influence by advancing the right incentives.

Bihar may be landlocked, but it has access to the sea through ports in West Bengal and Odisha that it can leverage. The Central Government has also prioritised the development of National Waterway 1, which passes through the heart of Bihar to the port city of Haldia.

Another advantage that Bihar has in its favour is adequate water supply and proximity to states having good mineral resources.

Even with the aforementioned possible routes available for Bihar to have economic prosperity through industrialisation, Prashant Kishor, sadly in his short-sighted bid to become the new progressive messiah, is promoting barriers against the same.

Though Prashant Kishor’s claims of government jobs not providing enough employment, and the promises of educating the young, supporting the old along with providing employment to the rest, seem to be fair, these are the basic premises that every aspiring Indian politician advances as lip service.

Very few leaders actually undertake any structural reforms that may upset entrenched interest groups due to political compulsions. It seems Kishor has decided not to be among those very few.

Aditya Bharadwaj is an Advocate at the Bombay High Court and a public policy professional. His interests lie at the intersection of business, finance and economics.