Bihar

Undermining Nitish: A Quiet Shake-Up That's Unsettling Bihar NDA?

Abhishek Kumar

Jun 30, 2025, 12:47 PM | Updated 12:48 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

As the dust settles on the early impact of socialism and the Mandalisation of Indian politics on Bihar’s fortunes, a new political generation—most of them familial inheritors of old warhorses—is bracing for a massive narrative shift.

One of the manifestations of this shift was recently visible when Tejashwi Yadav, often criticised as a product of nepotism, questioned the Nitish Kumar-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) for appointing family members to crucial political positions.

Just before Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s fifth visit to Bihar in this assembly election year, Tejashwi Yadav of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) launched a scathing attack.

Diverting attention from PM Modi’s inauguration of projects worth ₹10,000 crore, Yadav remarked, "If the Prime Minister is coming to Bihar, will he garland all three sons-in-law and welcome them on stage?" He added, "Will the Prime Minister explain what NDA means? Let me tell you—NDA stands for 'National Damaad Aayog' (Sons-in-law Commission)."

Before this direct attack on Modi, Yadav had been taunting Nitish Kumar himself, accusing him of abandoning his anti-dynasty image.

“We appeal to Chief Minister Nitish Kumar to form a Jamai Aayog (Commission for Sons-in-law),” he said. In other appearances, he went further, sarcastically suggesting a commission to appoint wives as well.

JD(U)'s Decline and Kurmi-Kushwaha Bind

Yadav’s jibes came after a series of controversial appointments signed off by Nitish Kumar in recent weeks.

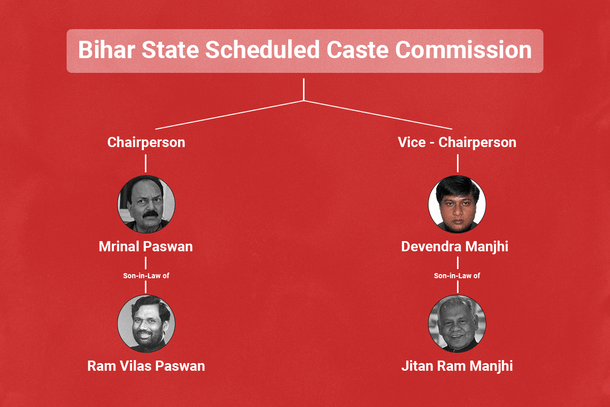

Among these, several involved sons-in-law of influential politicians like Ashok Chaudhary (JD(U) leader and minister), the late Ram Vilas Paswan, and Union MSME Minister Jitan Ram Manjhi.

The most contentious was the appointment of Mrinal Paswan, brother-in-law of Chirag Paswan and former government servant, as Chairperson of the Bihar State Scheduled Caste Commission (BSSCC).

Mrinal’s appointment is more controversial because of the perceived inertness on his part, since his LJP(RV) general secretary position is believed to be ceremonial in nature.

His deputy in BSSCC is Devendra Kumar Manjhi, son-in-law of HAM chief Jitan Ram Manjhi. Devendra, who contested the 2020 assembly elections from Makhdumpur, had also served as HAM general secretary and personal assistant to his father-in-law when he was CM in 2014.

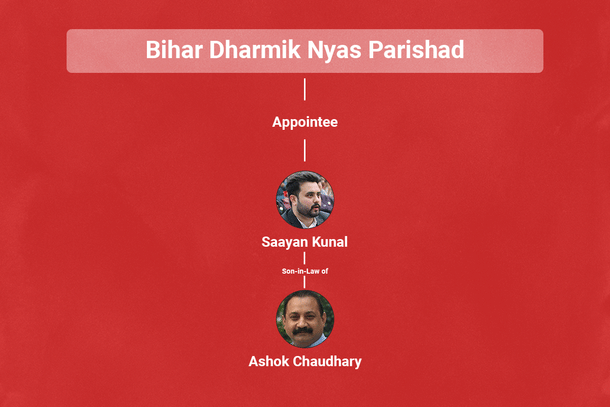

The third appointment flagged by Yadav is Sayan Kunal, son-in-law of JD(U) Minister Ashok Chaudhary and husband of Samastipur MP Sambhavi Chaudhary. Kunal has been appointed to the Bihar Dharmik Nyas Parishad. Facing backlash, Ashok Chaudhary distanced himself, claiming the appointment came from the RSS quota.

Kunal’s late father, Acharya Kishore Kunal—a former IPS officer—founded the Mahavir Mandir Trust, which operates multiple hospitals including the Mahavir Cancer Hospital.

The junior Kunal has also been active in religious affairs, especially after his father’s sudden death in 2024.

Another controversial name is Rashmi Rekha Verma, appointed to the Bihar State Women’s Commission. She is the wife of the CM’s Principal Secretary, Deepak Prasad. Tejashwi Yadav alleged that she hid this connection by listing her father’s name instead of her husband’s.

Tejashwi remarked, “She has been appointed as an educationist. Was no one else found? Shockingly, she even concealed her husband’s name and listed her father’s name instead.”

This is the second time this year the Principal Secretary has come under scrutiny. In March 2025, RJD MP Sudhakar Singh accused him of directing ₹25 crore from the Bihar Green Development Fund to his daughter’s company, Bodhi Centre for Sustainable Growth. Singh submitted evidence to the PMO, CAG, and Lokpal seeking investigation.

Sanjay Jha, JD(U) MP and Operation Sindoor’s international outreach member, faced criticism for a 2024 Presidential Order appointing his daughters, Satya and Aadya Jha, as Group ‘A’ panel counsel for Supreme Court litigation, positions typically reserved for lawyers with over 10 years' experience wherein exceptions are made in certain circumstances.

Critics questioned why specifically JD(U) national working president’s daughters were granted these exceptions.

Though Tejashwi is vocal on these appointments, his moral authority is weak. His entire political clan—Tej Pratap Yadav, Misa Bharti, Rohini Acharya, Rabri Devi, and Sadhu Yadav—has been parachuted into politics due to Lalu Yadav’s influence, who is the only one to have built an independent political identity.

Responding to Yadav, Ashok Chaudhary questioned Yadav’s family members’ qualifications.

“Tejashwi Yadav should practise what he preaches to others. Whose son is he? What are his qualifications? And what are the qualifications of his mother Rabri Devi to become Chief Minister of Bihar? Who are his two sisters: one is a party MP and the other contested the Lok Sabha poll unsuccessfully in 2024? People who live in glass houses should not throw stones at others,” said Chaudhary.

Defending his son-in-law, Chaudhary said, “Sayan Kunal has been my son-in-law only for 1.5 years. He is the son of Acharya Kishore Kunal, who built nine hospitals in the state, including a cancer hospital. Who doesn’t know Kunal Saheb?”

Meanwhile, Jitan Ram Manjhi has also come to a fierce defence of his family. He compared his son-in-law to Misa Bharti’s husband Shailesh and asserted that while his son-in-law is well qualified for the position, Shailesh stays at his in-laws' house and tolerates daily insults from Lalu and family.

Mrinal Paswan also defended his appointment as Chairman of BSSCC in a similar manner.

Nitish Kumar’s Image Under Siege

However, for the NDA, the question is not about the merit and demerit of individual appointments, but about the deviation from principles which Nitish Kumar has held virtually until the upcoming end of his political career. Nitish Kumar is not just a politician for the people of Bihar.

His moral attitudes regarding corruption and favouritism make him stand in a wholly different league from the established political class.

When he attacked Lalu Yadav and others for nepotism, the people of the state used to take it seriously since no one from his close family or friends was active in politics or held any powerful position. During his 2024 Lok Sabha elections campaign, Kumar had famously attacked Lalu Yadav for it.

"He appointed his wife when he was removed. Now, it is his children these days. He has produced so many offspring. Does anyone need to produce that many offspring? But he did. Now he has involved their sons, daughters, and everyone," said Kumar in Banmankhi, Purnia.

The man led JD(U) on the same principles and, until he remained strict on the enforcement of his principles, political doors for even his son Nishant Kumar remained closed. It was only towards the end of 2024 that the sluice gates opened, and his close circles convinced Nitish Kumar to launch his son — a project which remains pending to date for different reasons.

If and when his son gets ready for launch, it certainly will not bring much criticism from the state’s political establishment, since except Prashant Kishor, most are already neck-deep in this mud.

But JD(U) has not been the main beneficiary of this change of heart. Instead, that one silent nod by Kumar made it possible for NDA members with different interests to pounce onto the opportunistic wagon. The aforementioned appointments stand as strong testament to it.

Simultaneously, there is a growing consensus that Nitish Kumar is not fully on board with these decisions.

Kumar is now being seen as a ‘sorry figure’, someone whose legacy is being taken advantage of by politically unscrupulous elements in Bihar politics. The reason is now increasing consensus on his cognitive state, an issue first raised by the late Sushil Kumar Modi and later amplified by Prashant Kishor and now even Tejashwi Yadav.

If their assertions on Kumar’s health are to be believed, then he is just a signing authority in administrative and political matters of the state, while the real show is being run by a coterie of individuals Tejashwi Yadav loves to call the Bhunja Party.

Bhunja is fried flattened rice used as an evening snack in Bihar, commonly shared among close friends — especially professionals.

“The strength of the grand alliance, the public's resolve for change, and the direct defeat in the elections have left the stunned Chief Minister mentally absent, and now the corrupt Bhoonja Party might say anything, announce anything, or get anything done,” wrote Tejashwi.

The assertion that Kumar has suddenly deviated from one of the foundational principles of his politics, and the reasoning of his mental ineptitude, seems to be logically in line. However, it would be premature to conclude anything based on only one version of the story.

Another pattern which can be viewed as a manifestation of Kumar’s declining role in administration is the way JD(U) has been ignored in nearly a dozen appointments and reshufflings of different commissions.

In the last few weeks, the Bihar government has ramped up efforts to fill vacant positions in the Scheduled Caste Commission, Scheduled Tribe Commission, Minority Commission, Mahadalit Commission, Upper Caste (Savarna) Development Commission, State Food Commission, Price Monitoring Commission, Fishermen’s (Machhua) Commission, Madrasa Education Board, State Religious Trust Board (Dharmik Nyas Parishad), Bihar State Women’s Commission, and Bihar State Child Labour Commission.

Most of these commissions are idle in nature, with negligible ground visits or fact-finding missions, pending cases, pending meetings, delayed reports, and rule-based rather than spirit-of-rule-based bureaucracy confining the potential these bodies could achieve.

Resultantly, rather than competence of individuals appointed, local political and media discussions mainly focus on respective ‘quotas’ of members of the ruling alliance in the state.

For earlier appointments, JD(U)’s demands were fulfilled first. The latest iteration saw Nitish Kumar’s supporters being relegated lower down the preference hierarchy.

Even if one accepts that JD(U) not being given proper space could be part of a larger quid pro quo regarding seat sharing, what baffles most political pundits is that in allotting seats to members of Kumar’s own caste metric, BJP is replacing JD(U).

For regional politicians of the post-JP and Mandal era, it was prudent to build one vote-bank while using it as a base to diversify for getting into government.

For politicians like Lalu Yadav and Mulayam Singh Yadav, it was Yadavs. Muslims jumped their ships only after watching Yadavs in powerful positions willing to help them. Similarly, for Mayawati, it was the Jatav community, which set the base of vertical expansion within the Scheduled Caste fold.

Nitish Kumar was initially hesitant to jump on the caste bogey, but he changed his mind and attended the 1994 Kurmi Ekta Rally.

Within a decade of the rally, Kumar made a formidable base among Kurmis — the caste in which he was born — and Kushwahas. Together, both these castes make up more than 7 per cent of the state’s population.

Professor Ashwani Kumar, author of Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar, traces the empowerment of Kurmis and Kushwahas to the early 20th century when their Sanskritisation — the process where lower castes adopt the customs, rituals, and way of life of higher castes — began.

All three communities jointly fought the initial battle of equality, albeit with internal differences over accepting the leadership of Yadavs. Lalu Yadav and his preferential treatment of Yadavs amplified this fear, culminating in the 1994 rally, which, when viewed from hindsight, was a crucial node in Nitish Kumar’s journey from an engineer to Chief Minister of Bihar.

People from both these castes — especially Kurmi — got disproportionate assignments and appointments during Nitish’s rule, and NDA hugely benefitted from it. It also added EBC among its voters.

Combined, both these castes’ votes emerged as a strong pillar of counter to Lalu Yadav’s hold on Yadavs, who make up more than 14 per cent of voters. In the new appointment list, Kurmis and Kushwahas are hard to find — especially from the JD(U) quota.

From the JD(U) quota specifically, not a single Kurmi or Kushwaha has been named to any state-level body. It would be naïve to see it as a solitary damage, as the new political reality is gaining ground in the state.

The only notable Kushwaha JD(U) figure recently positioned in power was Bhagwan Singh Kushwaha, who was nominated to the Bihar Legislative Council in 2024. It belies common sense that this could be a temporary intra-alliance arrangement.

The fact that JD(U) failed to push even one Kurmi or Kushwaha onto these state panels is either a calculated political retreat or a staggering loss of intra-alliance leverage.

Upendra Kushwaha further complicates the equation. As a universally accepted leader coming from the Kushwaha community, he has traditionally acted as a glue between the BJP-led NDA and his own community. Keeping him happy is also crucial for the BJP-led NDA since his 2020 Assembly election overtures were also one of the reasons behind JD(U)’s decline.

“We all hold Chirag Paswan responsible for JD(U)’s numbers, but people often forget the divergence of Kushwaha voters. Upendra Kushwaha not being part of NDA also damaged the Kurmi-Koeri unity in that election,” said Professor Ashwani Kumar.

Upendra Kushwaha’s protégé, Angad Kushwaha, has found a place as a member of the Food Protection Commission — a decision which is being seen as the impact of Upendra Kushwaha himself.

On its part, BJP has also ramped up the process to court both communities. It officially began with the appointment of Samrat Chaudhary as its state President. Chaudhary is also Deputy Chief Minister of the state and is widely seen as BJP’s candidate for the chief ministerial position.

After BJP began its Kushwaha outreach, RJD also jumped in with heavy representation to Kushwahas in Lok Sabha elections. In the 2024 general elections, the Indian National Developmental Inclusive (INDI) Alliance gave 20 per cent of its tickets to the Luv-Kush duo in the state. The distribution of tickets was overseen almost single-handedly by Tejashwi Yadav himself.

Even after the election, Tejashwi Yadav kept promising Kushwahas proper representation.

Consequently, BJP had to assert more, and it did so by sending Sunil Kumar — a Kushwaha leader from Nitish Kumar’s stronghold Nalanda — into the Cabinet. The Cabinet expansion was also in the limelight for the promotion of Krishna Kumar Mantoo as IT Minister of Bihar.

Mantoo comes from the Kurmi community and was rewarded for organising the Kurmi Ekta Rally earlier this year.

It was the first such rally since the 1994 version. The 1994 version established Nitish Kumar as a Kurmi leader, and Mantoo’s promotion after the 2025 rally drew significant comparisons.

In the backdrop of these developments, Kurmi-Kushwaha leaders from the BJP and the Upendra Kushwaha faction getting preference hint towards JD(U)’s hold on these communities drifting away from it.

Is the Kurmi vote now taken for granted by JD(U)? Or worse, is it being deliberately undercut to reduce Nitish Kumar’s residual authority? There is no clear answer yet, but the fact that such questions are being asked is not a good sign for NDA.

Even the BJP’s strategy is selective. Not a single Kurmi leader has been appointed to a commission or board in this entire round of announcements — by JD(U), BJP, or RLM.

These patterns have left Kushwaha voters in a dilemma.

Amidst the pull from both BJP and RJD, significant diversion from NDA towards RJD — on the lines of the Lok Sabha election — is on the cards. However, Professor Ashwani Kumar asserts that Kushwahas will stick with NDA in this election. “They are part of the Luv-Kush combo. Where will they go except for Ram,” said Professor Kumar.

“Sociologically, this election is going to be contested on three poles — Swarajya (self-rule or self-governance), Suraj (good governance) and Samta (equality). Every community wants these three, which makes local candidate choice the key winnability factor,” he adds.

Politically, it is an indication that NDA cannot choose to ignore the demands of Luv-Kush in the upcoming elections, especially after the recent fumbles in these commissions.

Compromise, Crime and Corruption During Nitish's Raj

Compromising stands of Nitish Kumar on nepotism and the Luv-Kush vote bank come at a time when anti-incumbency against Nitish Kumar is at a multi-decade low. Kumar’s two administrative promises of controlling crime and corruption have been heavily compromised.

While falling bridges do make up for naked headlines about corruption, government servants — ranging from local clerks to District Education Officers — taking bribes is now an unfortunate fact accepted by people of the state.

Senior journalist Gyaneshwar often says that in Bihar, it is not about whether the official will take a bribe or not. It is whether he will get the work done after taking the bribe or not.

Raids after raids and seizures after seizures are now ineffective in an administration with multiple tainted senior officers handling powerful portfolios. The illegal liquor racket is believed to be the initial driver and inspiration behind it.

Pappu Yadav says that a sub-inspector level officer easily earns in excess of one crore per month. While that number may be hard to verify, videos of government servants daring to bash common people are an indication of how far the Overton window has moved in their favour.

Nitish Kumar was once known for controlling corruption, but now it is widely understood that there is not much difference between the corruption of the pre-2005 era and now.

What is different is the rate of crime, but then again, the Kumar government is losing out big on the perception battle here. In the last 12 months, the state has witnessed a rampant increase in isolated incidents of crime.

For an average Bihari, it has now become easier to think of shooting an enemy than going to a police station to seek justice — all thanks to corruption.

Around a year ago, Tejashwi Yadav began releasing crime bulletins that brought bad PR for the government machinery, forcing the state police to release their own version of events.

Even though Tejashwi is no longer releasing them, the incidents — especially emotionally charged ones — have not abated. In Buxar, a family feud turned bloody, while in Ara, a love story ended in multiple deaths.

Old-school murders, such as shooting someone en route, have shown signs of returning — the Chhapra incident being a prime example. Despite these occurrences, Bihar Police continued to deny any organised aspect to these crimes, a view also supported by crime analysts.

However, the recent shutting down of Naubatpur market due to extortion demands has raised many eyebrows, and heads have started to roll.

In Patna, the rapid succession of Senior Superintendents of Police — Rajeev Mishra, Avkash Kumar, and Kartikeya K Sharma within just 18 months — demonstrates how each attempted solution has only worsened the problem. Patna drew particular attention when young men were seen openly firing in public markets and even outside Tejashwi Yadav’s residence.

Frequent transfers and reappointments — 19 of them as recent as 21 June 2025 — have become the norm, as the government attempts to project responsiveness.

However, these reshuffles are often ineffective in addressing systemic corruption and the lackadaisical attitude of personnel. This perception battle arrived at a crucial juncture for Nitish Kumar.

Gen Z Foments Trouble

The Assembly elections of 2025 will be the first full-fledged state election in which Gen Z — making up a decisive chunk of Bihar’s population — will vote consciously.

For the youth of this generation, the 1990s are seen merely as a lost decade. The aspirational class views the RJD through the lens of Tejashwi Yadav, who urges his supporters not to behave like feudalists, distributes pens, and performed relatively well during his tenure as Deputy Chief Minister.

This is a generation that sees Rabri Devi through her positive characterisation in the web series Maharani.

With such a visual prefix, the reports of misrule during her tenure act merely as a useless suffix in the narrative war. Similarly, for them, violence was a last resort employed by Mohammad Shahabuddin.

To put it simply, a significant section of Gen Z perceives the violence of the 1990s less as conscious criminality and more as the grim inevitability of a caste-driven conflict.

Following the demise of Sushil Kumar Modi, BJP leaders have left it to their social media teams to highlight the past. The IT Cell seems to have overplayed its hand by simply repeating buzzwords, rather than documenting the gruesomeness of that era — a strategy that had proven successful for BJP in Haryana against Bhupinder Singh Hooda’s decade-long tenure.

Compounding NDA’s problems are the digital offensives of RJD and Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party (JSP). “This election is going to be fought on social media. What I mean by that is, the issues most amplified on social media will take centre stage,” said Professor Kumar.

Under Haryana import Sanjay Yadav, RJD has sharpened its social media game. Meanwhile, JSP is already a political outfit driven by a man widely regarded as a master political communicator and strategist.

Following his padyatra, Prashant Kishor launched the Bihar Badlav Yatra, whose rallies have drawn crowds of a scale rarely seen for pre-election events. Tejashwi Yadav has also hit the ground, engaging with people across different social and regional segments.

Unlike the NDA, both RJD and JSP have announced plans for cash distribution and voter incentives.

In contrast, the NDA is exhibiting sluggishness. Nitish Kumar’s reluctance to join the revdi (freebie) bandwagon is widely believed to be the reason behind this inertia.

The only remotely election-like announcements from the NDA have been the allocation of ₹2 lakh to 94 lakh families, an increase in pensions, and ₹4,000 crore earmarked for constructing marriage halls in the state.

Even in 2025, the NDA does not have a more trustworthy face than Nitish Kumar in Bihar. At the same time, his popularity is at an all-time low due to the three Cs: crime, corruption, and compromise.

The NDA will need to place greater emphasis on micro-social engineering and the hyper-localisation of its electoral approach — two phenotypes predicted by Professor Kumar.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.