Books

Book Review: What Does A 2003 Biography Of George Soros Tell Us About This Billionaire Critic Of Modi?

D V Sridharan

May 27, 2020, 12:33 PM | Updated 12:33 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

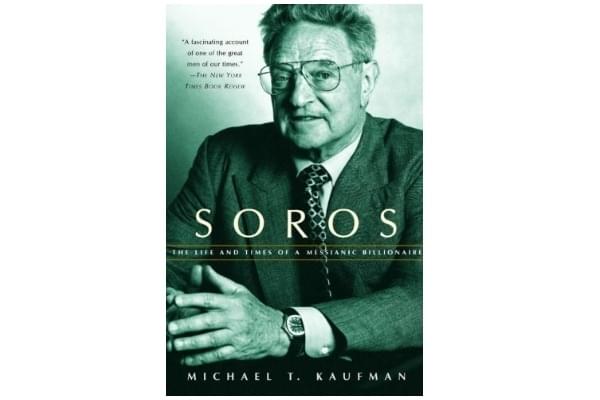

Soros: The Life and Times of a Messianic Billionaire. Michael T. Kaufman. Vintage. 438 pages. Rs 899.

In late 1990s, during the Asian economies’ currency meltdown, President Mahathir of Malaysia had lit into George Soros.

After castigating ‘Jewish traders’ in general for the crisis, he went on to single out Soros: “All these countries have spent forty years trying to build up their economy and a moron like Mr Soros comes along with a lot of money” [to wreck them].

My image of Soros took shape around that time and stuck.

I had imagined him as a brooding figure who lurks in the shadows, scanning the world for opportunities to make a killing. In an article, I had in fact called him a ‘lone wolf trader’ who meddles in countries’ politics to destabilise their markets to fish in them.

At Davos this January, Soros attacked India’s Prime Minister directly:

The biggest and most frightening setback occurred in India where a democratically elected Narendra Modi is creating a Hindu nationalist state, imposing punitive measures on Kashmir, a semi-autonomous Muslim region, and threatening to deprive millions of Muslims of their citizenship.

I was intrigued. Men chasing money don’t attack politicians directly. Even after Mahathir’s attack on him, Soros mostly defended himself and referred to Mahathir as ‘a menace to his country’ and that he was ‘Malaysia’s real problem’.

All said, it was only a response to a provocation and was confined to the realm of economics.

The attack on Modi however, was political and unprovoked.

I decided to find out more about this man who sounded like a rabble rousing politician.

Searching for a book to read, I avoided the many written by Soros himself and browsed several others.

Finally, after reading a sample, I chose Michael T. Kaufman’s Soros.

It was published in 2003, by when Kaufman had been a journalist with the New York Times (NYT) for 40 years. In that time and before that, the NYT was not the unbalanced pamphlet it has become today.

Kaufman says he told Soros that he believed “it was impossible for a rich man to be a good man”. Soros replied saying that was a reasonable position. He also promised to fully cooperate and give access to people and papers that mattered.

The book mostly succeeds in sounding credible, and it revealed to me a Soros I would not have suspected at all.

So what kind of man is he?

I came away from the book with many unexpected sides of the man, which also left me with some unanswered puzzles.

I remain angry about his ignorant foul-mouthing of India recently, but I have a guess that I shall hazard on how that may have come about.

For a start, he’s far from being an ugly rich man, let alone the stereotypical ‘Jew given to greed’.

The family name was ‘Schwarz’ before they officially changed it to ‘Soros’.

He was born Gyorgy Schwarz in 1930 in Budapest. His father, Tivadar, and mother Erzebet, though Jews, were hardly ardent ones. In fact, George was to describe his mother as “a typical anti-Semite Jew”. She was to convert to Christianity late in her life.

George’s dislike of fellow Jews began in Nazi-occupied Hungary. As a young teen, he often changed US dollars for elderly Jews and earned a small fee. Once he obtained a better rate at the synagogue than at the Exchange and requested a higher fee from his clients. They were unappreciative of his effort on their behalf and refused. This hardened him against all kinds of meanness.

Later in London as a student, he sought a scholarship from a Jewish charity. He thought their elaborate questioning amounted to distrust. A little later a professor, noting his difficulties, recommended his case to a Quaker charity, and a cheque arrived by post without a question asked of him.

These incidents were to guide his philanthropy, which he believed “should not be subjected to bureaucratic nitpicking. It was better to err on the side of generosity.”

His parents’ resilience and their attitude to money no doubt influenced their children.

During World War I, Tivadar, a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian forces, was captured by Russians and transported to Siberia. He made a fist of it in the camp by organising others, learning lock-smithy and Russian.

During World War II, after the Nazis occupied Hungary, Tivadar got busy and obtained false identity papers for the family and his friends and spread them across Hungary in order to escape Nazi Jew-hunters’ eyes.

When the couple migrated to the USA, George was already successful and wealthy, but his parents declined any support from him.

Tivadar tried his hand at running a Coffee House and failed.

He then applied for office jobs.

He lived a frugal life within the money he had. There was a tidy sum made from selling a house that his wife had inherited. Tivadar declared it belonged to people and created a family Trust using that money.

George’s mother was to live and die in a two-room apartment in Manhattan which she left to be run as a transit house for visitors on George’s philanthropic work.

The second surprise about George Soros is that his ambition was to be a philosopher.

He was reading Aristotle when 12 and was dreaming of a life of consequence. He admits to nursing a Messiah complex.

George gained his papers to exit Hungary, which was now in the Soviet Bloc and arrived in England, aged 17. London gave a chilly reception to the over confident young man, who spoke a strange English.

His life was lonely and he lived on very little money. He failed to get into the London School of Economics (LSE) in two attempts. When he finally gained admission, he felt he had arrived.

The fervour of the small campus awed him. “If the LSE lacked the hoary traditions of Oxford and Cambridge, it could boast of its influence on contemporary social and political thinking”.

Though he enrolled to study economics, he was attracted to philosophy.

At that time, Karl Popper was at the LSE and was considered a great mind of the century. To understand what moulded Soros’s politics and philanthropy, we need to know two of Popper’s ideas.

The first was—‘fallibility’.

Ralf Dahrendorf another philosopher, defines it thus: “In a world of uncertainty, we cannot know the truth, we can only guess. No amount of evidence can prove our guesses right, but often one fact suffices to prove them wrong.”

His second idea—“Open Society”—was explained by Popper himself in an eponymous book.

It was, in brief, this: “Societies that encourage continual arguments, refinements, and revisions about their own rules of governance are much more effective than those based on rigid dogmas.”

I will have occasion to recall this description of Open Society later but let me move on now and inform you that Soros named his organisation Open Society Institute.

Soros had attended none of Popper’s lectures, economics being his subject, but “he decided to ask Popper to be his mentor.”

Kaufman says Soros was an over-confident and almost arrogant young man. In a letter to Popper, that sounds somewhat condescending, Soros writes, “I agree with most of your statements (in ‘Open Society’). I believe however that a theory of historical development need not necessarily be historicist.”

Popper does call him over to meet him and quite simply tells him to write an essay on the difference between open- and closed-societies.

Soros sends his essay, Popper asks him to revise it, Soros does and sends it - and there, the engagement ends.

A later request that he read a Soros manuscript went unanswered.

Seventeen years later, Popper confessed to not being able to recall George Soros.

Soros went on struggling with his pursuit of philosophy. In one of his books, The Alchemy of Finance, he laboured on his idea of ‘reflexivity’. He was later to dismiss it thus: "I could have probably said it in five sentences”.

Tiring of philosophy, Soros turned to making money. He moved to the USA in 1956 with a plan to return to a full-time life of philosophy once he made $500,000 on Wall Street.

He turned out to be a money making natural.

“I don’t like money,” he was to say.“I am just good at making it.”

Years later he was to add that he was indeed interested in money though “in the same way that a sculptor must be interested in clay or bronze.”

What made him good at it were his traits: hard work, instinct, an eye for details, investing without delay based on his hunch and pulling out later, if necessary, readiness to take losses and move on and above all, a capacity for self-analysis and criticism of deals, and his remarkable ability to recall details of every trade.

Kaufman’s book narrates his successes on Wall Street with much detail.

Since my interest in the book was to understand the Soros behind the assault on Modi at Davos, I won’t dwell on his money making adventures. They are however exciting reading.

Let me record my third surprise: the man is not a sleazy operator.

That it should have come as a surprise at all is a measure of my own earlier estimation of the man, similar to Kaufman’s own belief, that a rich man cannot be a good man.

Soros has always worked on news available to everyone.

For example, in the currency operation that made him famous as ‘the Man who broke the Bank of England’ he saw through the untenability of British Prime Minister John Major’s rigid refusal to devalue the Pound. Soros betted on the Mark and the Yen and against the Pound.

He staked $10 billion on behalf of his fund’s investors and took away a billion dollars in profit.

Earlier after the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, his instinct was contrarian: He noted that though Israel had won the war, it had lost much of its military hardware. Soros quickly invested in US armament firms.

He never sold a hedge fund product or an investment opportunity without some of his own money in it. He never concealed bad news about his business nor donated with an eye on a benefit to his business.

His lifestyle has been quite ordinary, as billionaires’ go. He has never owned a plane, and flew only business class for a long time. His idea of relaxation was five hours of chess or competitive tennis. He doesn’t socialise much. He reads voraciously.

Soros left his first wife not for another woman but to recreate a simpler life for himself.

He moved into a poorly furnished, tiny apartment. “… he wanted to own nothing. He didn’t want to be bothered by possessions. He wanted a totally new life.” He didn’t even own a car.

By now, he obviously had way more than the half million he had as a target to indulge in philanthropy, his second choice for life after philosophy.

The book reveals a man proactively searching for causes he could support.

He had three pet objectives: promote free markets, personal freedom, and free speech.

He had a dislike for nationalism, communism and Freud. (He thought more kindly of Freud when he underwent therapy and declared it worked for him).

The Helsinki Final Act of 1975 set up the stage for him to play the high profile philanthropist.

The Act was to strengthen European states’ security and development. The Soviets and its allies signed it to gain recognition for their postwar borders. In return, they consented to be questioned on human rights, earlier resisted as a sovereign matter.

And that turned out to be the wedge, that split the Soviet Bloc.

A little later, he was to meet Aryeh Neier. Neier and Soros shared a phobia for nationalism and the big state. Naier, who was born in Nazi germany, went to Cornell and Yale and developed a passion for all manner of rights issues.

He then headed an organisation called Helsinki Watch which kept a vigil on signatories for compliance with the Act. Every Wednesday morning, there was a meeting at 8 in his office which featured a dissenter from inside Soviet-bloc states already in turmoil.

The world was changing. These speakers were describing the woes of ordinary people. Soros listened without uttering a word.

Soon he was spawning Soros Foundations in all the agitating countries, manned by people he had met through Naier or similar people he had befriended.

His munificence to countries that floated free when the Soviet Bloc came apart is well told by Kaufman. These are inspirational adventures.

He was sending in photocopiers and printers to Hungary for dissemination of information from libraries.

Russian scientists who were impoverished by the chaos were given $500 a month in a project that amounted to $100 million.

He paid for a robust Internet network connecting Russian research stations.

He spent $13 million to support several thousand Yugoslav students stranded overseas as their country was breaking up.

He had a water treatment plant built for war-ravaged people of Bosnia; and there was a foolhardy mission to Chechnya to rescue elderly Russians that ended in the loss of his key man.

In short, he was everywhere in that Europe in a flux. His spends amounted to more than a billion. Kaufman’s telling of the tales is enjoyable.

Let me record yet another surprise, the fourth: In all his interventions in countries, he seldom operated covertly. Throughout that period, he met with strange activists and dissidents who often proposed extreme ideas. There were suggestions that he send arms and support to Afghanistan and Poland. He declined.

My journey to know Soros through Kaufman’s book ends in 2003. In its concluding pages, we have a Soros preparing to wind down both in his activism and business. He had institutionalised both.

Going over his life again, even while noting the surprises I have described, I was left with three puzzles.

In the light of his attack on India and China in Davos, I was curious what his earlier views were on both.

As for China, he had made a foray into it with his philanthropy and quite quickly retreated finding it impossible to cope with China’s ways.

The first reference to India occurred in the book when I was more than half-way through it. Aryeh Neier, when he came on board as a full timer in late 1993, was very interested in Soros starting a foundation in India.

Soros brushed him aside saying he was an investor in India and that his rule was, “no philanthropy where he was an investor and no investing where he was a philanthropist.” And that was that. India opening its markets may have influenced him.

Nothing more is heard on India in the book.

So what brought on the Davos attack on Modi and India?

My guess is his statement was prepared by a proxy or two from the NAC (-National Advisory Council), the club that steered the elected Indian government between 2004 and 2014.

Incidentally, an NAC member, Harsh Mandar, sits on Open Society Foundation’s Human Rights Advisory Committee. Also incidentally, there was the matter of India asking a Soros-pet, Amnesty International, to wind up.

One other puzzle remains: How clear is Soros’s understanding of nationalism?

As far as I can tell, the nationalism of Nazis has deeply affected Soros to misapply the word as a careless epithet. He came to believe in ‘universalism’ as the remedy. Given that, any country that resisted dilution of its unique culture, ends up as being nationalist in his eyes.

Has he been consistent with this position?

Kaufman, explaining Soros’s extra fondness for Hungary, says this: “Years later (Soros) would say the main reason for his choice was ‘the damned language’. The intricate and bizarre Magyar tongue, so bewildering to outsiders, bound him to other Hungarians.”

Here’s Kaufman again: Soros claimed “he was not a nationalist, nor was he drawn to (Hungary) by nostalgia. Susan, his wife, did not like it at all, finding the intellectual pretensions and hauteur of many Hungarians, hard to take…. She did not hide her contempt for many of the Hungarians with whom George was spending more and more time. “I didn’t like the chauvinist aspect of the society, says Susan. “It was very much male. I didn’t like the bravado. You know, everything Hungarian is best. That used to offend me, this feeling that America is a provincial place and that Hungary is the capital of the world.”

“It’s okay, George!,” I longed to say. "Everyone likes to brag about his country. It’s not nationalism. It’s called cultural affinity.”

An internationalism that seeks to render all people in its own image is the greatest threat that we face today.

Has Islam’s ideology troubled Soros at all?

There is not a single mention of Islam in the entire book. Islamism unapologetically and aggressively agitates for a world wherein there would not be an idea it needs to tolerate. It brooks no criticism or reform. Its demand for submission to none but Allah is nothing less than a commitment to an unfree polity.

Soros had not satisfied Popper with his essay on the difference between open- and closed- societies. And yet he has remained a Popper devotee.

Surely he was aware of these most commonly quoted words of the philosopher: “…if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed and tolerance with them.”

Did Soros ever test Islam by Popper’s dictum?

Now, let me recall an earlier quote:

“Societies that encourage continual arguments, refinements, and revisions about their own rules of governance are much more effective than those based on rigid dogmas.”

Has Soros ever tested Hinduism and India by this Popper dictum? Were he to do that, the difference between closed- and open- societies will become obvious.

D V Sridharan was a sea-going engineer in the 1960s. For the last 40 years, he has been passionate about the environment, especially water conservation and eco-diversity. He’s currently in the second decade of his land regeneration work at pointReturn, 100km south of Chennai. He tweets at @strawsinthewind.